Українською читайте тут.

An analysis of Kremlin propaganda on the social network X, based on the examples of Russia's embassy pages in the United States and South Africa.

Russia systematically attempts to promote its agenda to foreign audiences, shaping a positive image as a "reliable partner" or "savior," with particular attention to countries of the so-called Global South. To achieve this, it utilizes not only state propaganda media or proxy media networks but also the "buying" of local bloggers or social media bot farms. It also involves diplomatic institutions and their social media accounts in spreading propaganda.

In this study, we aim to investigate how Russian diplomats and politicians shape Russia's image abroad. For analysis, we selected the official X (Twitter) accounts of Russian embassies in South Africa and the United States. The authors aimed to explore the influence on public sentiment in one of the key countries of the Global South and to identify differences between the rhetoric of propaganda in this country and the "diplomatic language" used on similar pages in the United States. For this study, we analyzed over 12,500 posts on the official accounts of the respective Russian embassies from the beginning of 2020 to September 2024. We also compared these posts with those on the accounts of the Ukrainian embassies in these countries for the same period.

Weekly Tweet count of Russian and Ukrainian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa

Research methodology

The social network X (formerly Twitter) was chosen for this study for several reasons. According to data from Statista, over 70% of the network’s users were under 35 years old as of April 2024. The platform had 611 million monthly users and ranked 12th most popular globally.

In the post-COVID period, there was an increase in social media usage in South Africa, driven by the rise in mobile app usage. On X (formerly Twitter), up to 60% of South Africans aged 18 to 64 are active monthly. Among comparable audiences in South Africa and the U.S., 82% of South African Twitter users are younger than 44, with a third under 25. As of September 2023, 42% of U.S. adults aged 18 to 29 used X. The younger audience on X is particularly interested in analyzing reactions to propaganda content, as they lack the Cold War-era stereotypes and direct confrontation between the USSR and the U.S.

Unlike Meta's products (Facebook, Instagram), X (Twitter) has not been blocked in Russia since 2023. Twitter also hasn’t experienced slowdowns from Russian providers, unlike YouTube. Additionally, X, unlike Telegram, has no Russian co-founders. And unlike TikTok, Snapchat, Douyin, or Kuaishou—which are primarily focused on short video content for the Chinese market—X is not banned for use by officials in some American and European states, which would complicate cross-state communication comparisons if scaled. TikTok is also not as widely used by diplomats.

Despite the accessibility and popularity of X, its content is less moderated for disinformation. Only in September 2024 did the company release its first report on restricted or removed content in two years. This comes partly due to criticism of billionaire Elon Musk, who acquired the platform in April 2022 for spreading misinformation and fake news on his own X account. Musk, in turn, has described himself as a proponent of "free speech."

It is also important to note that both Ukraine and Russia, like most countries, maintain embassy pages on this platform, allowing for comparisons between them and the assessment of their content and impact within a single social media platform.

This study focuses on analyzing the X (Twitter) pages of the Russian and Ukrainian embassies in the United States and South Africa. The selection of embassies in these countries is influenced by several factors. First, the geopolitical alignment of the countries: According to the Kiel Institute, the United States is the country that has provided the most military aid to Ukraine to repel Russian aggression. In contrast, in March 2022, South Africa abstained from voting on a UN resolution supporting Ukraine's territorial integrity that condemned Russian aggression. Additionally, since 2011, South Africa has been a member of the BRICS intergovernmental organization and is a key country in the Global South, whose support for the Peace Formula is a target of Ukrainian diplomatic efforts. Similarly, Russian propaganda efforts aim to persuade both ordinary people and elites in Global South countries to support Russia or ignore Russia's violations of international law.

English is the official language in the United States and the second most spoken language in South Africa. The Ukrainian and Russian embassies in each of these countries maintain their Twitter pages in English. The shared language of the publications helps avoid translation and potential distortions of context caused by message translation. These distortions could potentially impact the study's results.

For analysis, we selected the period from January 1, 2020, to the data extraction date, September 15, 2024. This extended period was chosen to compare publication trends before and after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The number of unique posts in the analyzed dataset is 12,517.

The key hypothesis of the study was the assumption that the Twitter pages of Russian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa systematically disseminate Russian propaganda. In contrast, the Ukrainian embassies in these countries are insufficiently effective in conveying the positions of the Ukrainian state.

The objectives of the study were: compare the key numerical indicators of the reach of posts by the analyzed embassies on X; determine the role of public communications in spreading propaganda on the official pages of the Russian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa; and compare the key approaches to information dissemination used by the embassies' Twitter pages, specifically through retweets (reposting), engagement of external experts, sharing of posts from state representatives, and the use of hashtags to enter X’s trending topics.

After extracting data from the Twitter pages of the Ukrainian and Russian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa, the key stages of analysis included the following steps: analysis of the quantitative indicators and tweet dynamics; categorization of posts by topic; identification of key individuals, country names, organizations, or events within the dataset; and analysis of the most common words to determine shifts in the embassies’ rhetoric on Twitter.

Annual Tweet count of Russian and Ukrainian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa from 2020 to September 15, 2024

As of October 2024, the Russian embassy in the U.S. has 136,400 Twitter followers, while the Ukrainian embassy has 25,400 followers. In South Africa, the Russian embassy is followed by 181,700 Twitter users, compared to almost 2,600 thousand for the Ukrainian embassy. This disparity in follower count impacts the reach and citation of posts by Ukrainian embassies. Due to a decrease in tweets by the Russian embassy in the U.S. since the end of 2021, the Ukrainian embassy in the United States has achieved similar average engagement on its tweets. From January 1 to September 15, 2024, the Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. averaged 49 retweets per week, compared to 44 for the Russian embassy. Over the same period, the average tweet by the Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. had 211 shares on X, while the Russian embassy's tweets averaged 162 shares. This parity in metrics and the tendency for the Ukrainian embassy to occasionally surpass the Russian embassy can partly be explained by reduced activity from the Russian embassy in the U.S. (as illustrated in the infographic above). Since March 2023, the Russian embassy in the U.S. has posted fewer tweets than the Ukrainian embassy. However, in South Africa, the Russian embassy's activity remains high. In the first nine and a half months of 2024, the Russian embassy in South Africa posted three times as many tweets as the Ukrainian embassy — 1,006 compared to 334.

How government communications become propaganda

In the analyzed dataset, there were only 38 posts that the embassies retweeted without additional comments. The Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. retweeted 22 such posts, and the Ukrainian embassy in South Africa retweeted five. Ukrainian embassies primarily retweet posts from government officials and agencies, including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada Ruslan Stefanchuk, Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Deputy Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha, the Ukrainian Ambassador to the U.S. Oksana Markarova, and the Crimea Platform. Additionally, the Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. once retweeted information about an Atlantic Council event focused on Ukraine’s energy resilience.

In eight out of 11 instances, the Russian embassy in South Africa retweeted its own posts without additional commentary. It also retweeted posts from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, including one of its verified pages on X titled “Russia.” According to the page description, "Russia" offers “fresh ideas from Russia, home to over 190 ethnic groups and authentic cultures, spanning 11 time zones and seven climate zones.” The page features content such as nature photos, references to historical events, posts about famous birthdays, modified Soviet cars like Lada or Moskvich, and Russian culture, which often includes the accomplishments or representatives of various ethnic groups that Russia traditionally claims. For instance, on October 9, "Russia" published a tweet commemorating the birthday of Ivan Piddubny, a wrestler born in what is now the Poltava region of Ukraine, who was active from the late 19th century to the first half of the 20th century. Another example of cultural appropriation includes a post celebrating cosmonaut Pavlo Popovych, referring to him as a "Soviet" pilot while omitting that he was born in the Kyiv region and was the first Ukrainian in space.

Three more instances of retweets by the Russian embassy in South Africa involved retweeting other users aligned with Russian propaganda. On June 29, 2024, the embassy reposted a tweet by a verified yet anonymous social media user “Lord Bebo,” featuring a video and caption that claimed, “Ukrainian soldiers are literally grabbing bus drivers while on duty.” As of late October 2024, the anonymous account “Lord Bebo,” created in April 2019, has nearly 495,000 followers on Twitter and an additional 48,500 on a similarly named Telegram channel linked in the profile. The authors or author of the “Lord Bebo” account claim to be “against hypocrisy and fake news.” However, nearly all posts are exclusively disinformation content focused on Ukraine, Israel, and U.S. elections.

On September 7, the Russian embassy in South Africa retweeted a post by writer Thomas Fazi, in which Fazi mocked claims that Russia might be involved in sabotage at European military facilities. Previously, Fazi had written that Orthodox Christians are persecuted in Ukraine and that the “EU humiliates Hungary.” In July 2024, Thomas Fazi was among the “intellectuals” who signed an open letter urging Western politicians not to invite Ukraine to NATO to “avoid provoking Russia.” On September 26, OCCRP journalists published an investigation detailing how Russians recruit Europeans for sabotage operations.

In another example, on September 12, 2024, the Russian embassy in South Africa retweeted a tweet by American political commentator Jackson Hinkle without adding any comment. Hinkle stated that “God is on Putin's side.” The conspiracy theorist tweeted a selfie from Moscow, noting that a memorial had been set up outside the U.S. embassy in Russia for another pro-Russian propagandist, Gonzalo Lira. The Security Service of Ukraine detained Lira in May 2023, charging him under Article 436-2 of Ukraine's Criminal Code for "justifying, recognizing as lawful, or denying the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine and glorifying its participants." The court ordered preventive detention with the possibility of release on bail. After posting bail, Lira attempted to flee the investigation and tried to leave Ukraine. He was re-arrested in the Zakarpattia region and returned to a detention facility in Kharkiv. In January 2024, Lira died in Ukrainian custody, reportedly from pneumonia. Propagandists are now attempting to portray his detention and death as “proof” that the “Kyiv regime eliminates journalists and subjects them to torture.”

Users on X who were quoted three or more times by the Russian and Ukrainian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa from January 1, 2020, to September 15, 2024

Embassies shared links to posts by other X users with accompanying comments in 908 instances. In cases of retweets without added text, the Russian embassy in the U.S. frequently mentions relevant ministries, state leaders, and officials. They also share tweets with their own commentary and "tag" foreign officials or politicians to invite discussion and provoke conflict.

For instance, in May 2020, the Russian embassy in the U.S. shared a tweet tagging the U.S. State Department spokesperson regarding the alleged pepper-spraying of a correspondent from the Russian state-affiliated outlet RIA Novosti in Minneapolis. In December 2021, they did so again to accuse the U.S. of establishing “military bases around Russia’s borders,” a claim used by Russia to justify its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

The Russian embassy in South Africa more frequently mentions foreign individuals who support Russia or promote narratives favorable to Russian propaganda than its counterpart in the U.S. Over the analyzed period, this embassy cited and referenced tweets from pro-Russian expert and Irish businessman Chay Bowes 14 times. In May 2023, Bowes addressed the UN Security Council, claiming that NATO’s support for Ukraine escalates the armed conflict.

In a tweet from August 2023, retweeted by the Russian embassy in South Africa, Bowes alleged that “Ukraine is shelling civilians with American, British, and French weapons,” suggesting Ukraine deliberately targets civilians in response to Russian military aggression. The Kremlin also uses this propaganda narrative to continue its aggression against Ukraine.

American conspiracy enthusiasts also contribute to Russian propaganda in South Africa, such as blogger and former Fox News host Tucker Carlson. He visited Russia in February 2024, giving Vladimir Putin a platform to speak, and in April 2024 published an interview with Alexander Dugin, a key ideologue of the Putin regime.

The Russian embassy in South Africa tagged Carlson 30 times but shared only six of his tweets, one of which praised the beauty of the Moscow metro.

“How is it that Russia, a country once described as a gas station with nuclear weapons, has a metro station used daily by ordinary people to commute to work and home that surpasses anything in our country?” — This quote by Tucker Carlson, which aligns with the Soviet-era myth of a “decaying West,” was shared by the Russian embassy in South Africa on February 15, 2024.

The Russian embassy in the U.S. on X is less likely to quote or share tweets from pro-Russian experts and conspiracy theorists. However, it does cite journalists who interview Russian diplomats. For instance, since May 2022, they have mentioned Newsweek journalist Tom O'Connor six times.

In one such tweet, the Russian embassy in the U.S. shared O’Connor's post about his interview with the Russian ambassador to the U.S. for Newsweek, saying, “The U.S. is engulfed in a wave of Russophobia, fueled by media under the encouragement of authorities. This situation has reached the worst forms of anti-communist paranoia and McCarthy-era witch hunts.”

In terms of relevance and frequency, after retweeting state entities and “experts,” the third most common category shared by Russia’s official X accounts are tweets from various Russian propaganda outlets. Among these, the English-language African branch of the Russian propaganda outlet Sputnik, which only joined X in May 2023, is frequently cited. By September 2024, this page had over 4,000 followers. For comparison, the French-language page Sputnik Afrique, launched in 2011, has over 108,000 followers. This reflects an attempt to “redirect” audiences from the more popular Russian embassy in South Africa account to this newly created page.

Russia uses the Sputnik Africa page to promote the views of Russian officials or to showcase Russia's "charity" towards Africa. For instance, on June 4, 2024, the African branch of Sputnik cited Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, who stated that Russia had delivered 380,000 tons of food to Africa over the past five years "despite obstacles created by the collective West." These tweets omit any mention of why Russia faces sanctions and how Russia obstructed Ukrainian grain exports in 2022-23 and likely exported stolen grain from occupied Ukrainian territories to other countries.

Tweets by Russian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa: "Preserving Ourselves" versus adapting to "international market demands."

For foreign audiences, Russian diplomats use established terminology on their official X pages to describe historical events. For example, the Russian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa have used the term "World War II" at least 352 times instead of the Russian equivalent "Great Patriotic War." The term "Great Patriotic War" is commonly used in Russian media and promoted in countries that were part of the USSR or the "socialist bloc." In the analyzed tweets, "Great Patriotic War" was used only 89 times. This suggests an effort by Russian diplomats to make the "Russian version of history" more palatable to an international audience.

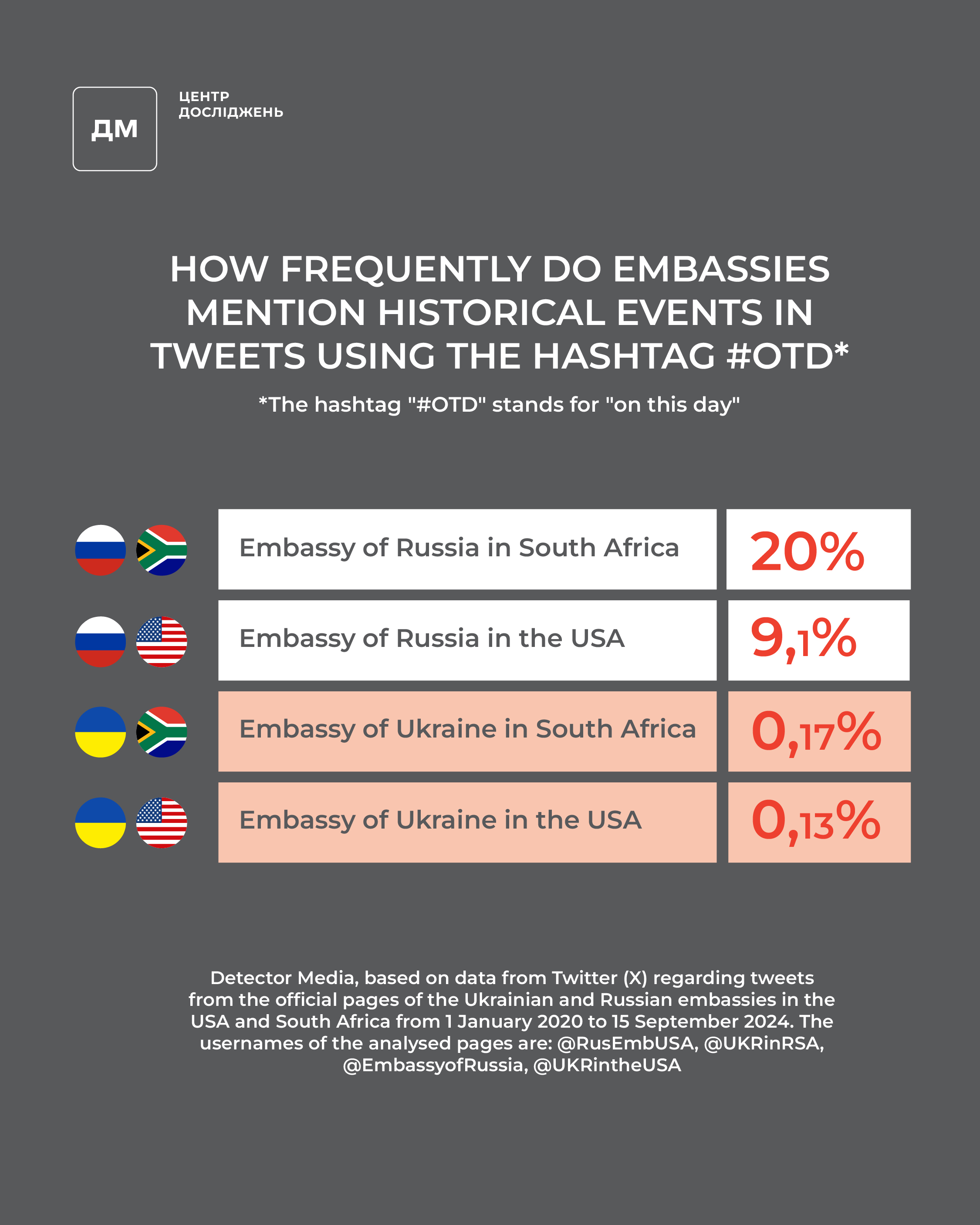

The scope of historical manipulation in tweets by Russian embassies is highlighted by the hashtag "#OTD," meaning "on this day." Analyzed embassies use this tag to mark anniversaries and commemorative dates. For the Russian Embassy in South Africa, posts with this tag made up 20.9% of all posts during the analyzed period, while for the Russian embassy in the U.S., it was over 9%. In contrast, the Ukrainian embassies in South Africa and the U.S. used this hashtag in only 0.17% and 0.13% of their posts, respectively. Given that appearing on trending pages helps content reach a local audience, this high frequency of hashtag use illustrates how Russia leverages history as a tool for propaganda.

Using historical events mentioned in tweets can be a convenient way to maintain publishing frequency and promote desired narratives about the past without violating X's content distribution principles. This approach involves frequent posts with trending hashtags, keeping posts in the limelight. Such content can be planned in advance and updated annually with retweets.

The 50 most popular people, organizations, countries, or events in tweets by Russian and Ukrainian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa, cited weekly from January 1, 2020, to September 15, 2024

Since 2021, the Russian Embassy in the U.S. has reduced the frequency of posts and also decreased the use of Russian propaganda markers such as "Nazi" and "neo-Nazi," as well as terms Russia’s agitprop labels as opponents: Washington, EU, NATO, Ukraine, Poland, etc. The trend at the Russian embassy in South Africa is the opposite. For instance, mentions of "Washington" by the Russian embassy in South Africa exceed those by the Russian embassy in the U.S. with 242 mentions versus 115. In both embassies, these terms are used almost exclusively in a negative context, highlighting how Russian diplomacy is intertwined with Russian propaganda.

There are more examples of historical manipulation in tweets from the Russian embassy in South Africa. On May 9, 2022, the official page of the Russian embassy in South Africa shared an article by press attaché Alexander Arefyev, also published in local outlets (like Pretoria News) in the sponsored category. In it, Arefyev wrote that Russia, "alongside former Soviet republics," celebrates "Victory Day" on May 9, and he echoed Putin's version of history, focusing on the "generation of victors" and stating that the decisive defeat of Germany occurred on the Eastern Front of World War II. Arefyev then appeals to local readers, claiming that Russia and African nations stand "on the same side of history" while referring to Ukraine as a "haven for neo-Nazism with the full support of the West." This article aims to fuel anti-Western and anti-colonial sentiment among at least part of the South African audience and fully propagates the Russian-Soviet version of history. Arefyev explicitly writes that "World War II happened largely because the West appeased Nazi Germany," adding that the "West is doing the same with Ukraine today, ignoring the lessons of history." Of course, the Russian diplomat omits any mention of Stalin and Hitler’s agreement to divide Poland (known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact).

In total, 108 tweets were dedicated to the celebration of May 9 on the Russian embassy's Twitter account in South Africa, as analyzed in the sample. Among these was a series published in Twitter threads on the “nine symbols of victory,” tagged with #SymbolsOfVictory (#СимволыПобеды). These tweets appeared in both English and Russian, including posts about the significance of the “Hero’s Golden Star” and those awarded this Soviet medal.

Russians also brought a late Soviet tradition to South Africa, familiar to many from childhood—ritual visits of war veterans before May 9. Russian diplomats located one veteran in Johannesburg, and the embassy’s page features posts about the “Immortal Regiment” march held in Johannesburg in 2021. Historian Timothy Snyder notes that “Immortal Regiment” marches are part of the Russian myth surrounding World War II, a myth of a golden past and lost greatness that can be restored through a new act of violence—the war against Ukraine.

It’s important to note that not all readers of the Russian embassy in South Africa’s tweets accept Russian propaganda uncritically. For example, in 2022, after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, many critical comments, caricatures of Putin, and calls for Russia to leave Ukraine and South Africa in peace appeared under the embassy’s posts.

In the embassy's Twitter account, phrases like "neo-Nazis" and "neo-Nazism" were used 74 times over the analyzed period. After the invasion began, most of these tweets involved quoting representatives from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, such as Maria Zakharova, Sergei Lavrov, or Putin himself. One post directed at a South African audience shared Putin's statement on the alleged organizers of a terrorist attack at Moscow's "Crocus City Hall" shopping center:

“President #Putin: This brutality [the attack at ‘Crocus City Hall’] can only be part of a long chain of attempts by those who have been fighting our country since 2014 through the neo-Nazi Kyiv regime.”

However, Russia had already been promoting the narrative of a "neo-Nazi coup in Ukraine" through the Twitter account of its embassy in South Africa. For instance, in 2020, they mentioned pro-Russian blogger Oles Buzyna, referring to him as an "opponent of the neo-Nazi coup in Ukraine" and accused Ukrainian authorities of having "forgotten" to investigate his murder.

At least ten posts on the Russian embassy’s page in the U.S. stated that “the U.S. is profiting from the war in Ukraine” or that “the conflict in Ukraine is good business for the U.S.” In January 2024, the embassy’s page shared speeches by U.S. presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, a conspiracy theory supporter, claiming that American private military companies are already taking over farmland in Ukraine.

The official account in South Africa has also spread misinformation. For example, it claimed that Volodymyr Zelenskyy allegedly bought a £20 million estate from King Charles III of the United Kingdom. This falsehood was debunked by Detector Media's fact-checkers, and Twitter users mocked the Russian embassy in South Africa for this lie. Platform X added a note indicating the falseness of this post on the Russian embassy's page in South Africa, but the tweet containing misinformation was not removed.

Media campaigns and tweets of Ukrainian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa

From 2020 to 2021, the official X page of the Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. posted about events related to Russia's aggression against Ukraine, which began with Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Representatives from Ukraine’s foreign ministry called for stronger sanctions on Russia and highlighted Russia’s crimes to the international community.

For example, on September 4, 2021, when Russian occupation authorities in Crimea detained Nariman Dzhelyal, the deputy head of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis, along with at least 45 other Crimean Tatars, the Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. shared Ukraine’s stance and also quoted a statement from the U.S. State Department demanding the immediate release of Dzhelyal and other detained Crimeans. Dzhelyal was eventually released from Russian captivity on June 28, 2024.

During 2020–2021, calls to hold the aggressor accountable and to draw attention to its crimes sometimes took precedence over information aimed at Ukrainian citizens in South Africa about the COVID-19 pandemic, which also falls within the duties of Ukraine’s diplomatic missions. These tweets included information on repatriation options for Ukrainian citizens and provided contacts for Ukrainian embassies and consulates in South Africa and other African countries. Once the COVID-19 pandemic became more controlled, the Ukrainian embassy in South Africa’s page began to feature more informational publications, such as stories about notable Ukrainians or interesting places to visit in Ukraine.

In December 2021, shortly before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian embassy in the U.S. clarified on X that Ukraine was not asking the U.S. or Americans to fight for it but was requesting arms and military equipment to continue defending itself against Russia. These statements came from tweets and remarks by then-Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba and Ukraine’s Ambassador to the U.S., Oksana Markarova.

Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa kept audiences informed about the war's progress. In the U.S., they portrayed Ukraine as successfully resisting the aggressor but needing support. Between February 28 and September 5, 2022, the Ukrainian embassy's page in the U.S. posted 62 tweets with infographics detailing Russian army losses in Ukraine.

Reporting on Russian war crimes also became a significant focus on the Ukrainian embassy's page in the U.S. These posts often included hashtags like "#StandWithUkraine," used at least 72 times after February 24, 2022, "#StandWithUkraine" (41 times), and "#StopRussianAggression" (11 times).

Through the Ukrainian embassy's page in the U.S., key events triggered by the full-scale invasion became more visible to the international audience. For example, in May 2022, the embassy highlighted civilians who had sought refuge at the Azovstal plant in Mariupol as Russian forces stormed it. A month prior, they posted evidence of Russian war crimes committed during the occupation of parts of Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy regions.

The embassy’s page in the U.S. has continued to be a tool for sharing updates on Ukraine, countering Russian information influence, and coordinating information campaigns. Since early 2023, tweets calling for a boycott of Russian athletes and urging the exclusion of Russian competitors from the 2024 Paris Olympics appeared on the embassy’s X page. This campaign included posts showing destroyed Ukrainian sports facilities and evidence that Russian athletes were not truly “neutral.” The campaign lasted until the start of the 2024 Olympics.

From 2022 to 2024, the Ukrainian embassy’s X account in South Africa shared information about the full-scale war in Ukraine and condemned Russian aggression, describing the destruction of Ukraine’s agricultural sector, food supplies, and logistics by Russian forces. They showed that, despite the aggression, Ukraine continued to supply the world with food in contrast to Russia, which was endangering millions with the threat of famine. Some posts focused on Ukraine’s humanitarian initiative, Grain from Ukraine, aimed at facilitating the transport of agricultural products from Ukraine and preventing hunger in vulnerable African and Asian countries. The embassy noted that 32 African countries rely on Ukrainian grain. In several posts, the Ukrainian embassy in South Africa also shared the importance of Ukraine for global food security, linking to the website war.ukraine.ua for further information.

Conclusions

The tweets from the Ukrainian and Russian embassies in the U.S. and South Africa reflect contrasting approaches by Ukraine and Russia in promoting their national interests and the interests of their citizens. Ukrainian embassies take a more reactive stance, using X to increase visibility around Russia’s violations of international law, while Russian embassy publications construct an alternative reality of the informational space.

Russian diplomatic missions have turned state communications into a tool of propaganda, moving away from traditional diplomatic language in favor of manipulative narratives. This is especially evident with the Russian embassy in South Africa, where one-fifth of all posts use the hashtag "#OTD," presenting distorted historical facts shaped by Russian propaganda. To expand the reach and enhance the reception of the "Russian version of history" by international audiences, Russian diplomats avoid terms imposed by Russian propaganda in former Soviet or socialist bloc countries. For instance, the embassies use "World War II" instead of the Soviet-era "Great Patriotic War."

Technologically, Russian representatives effectively exploit the content promotion features on X, evidenced by their significantly higher follower count and interactions. The Russian embassy in South Africa amplifies its narratives with pro-Russian experts and bloggers, while the embassy in the U.S. focuses on provocative engagement with American officials.

Ukrainian embassies, with fewer resources and a smaller audience, focus on targeted information campaigns, such as exposing Russian war crimes, opposing Russian athletes' participation in international events, and clarifying Ukraine's role in global food security. While this strategy may have less reach, it allows Ukraine to convey its stance to target audiences more precisely.

To enhance communication effectiveness, Ukrainian diplomatic missions should emphasize cases where Russia appropriates the histories of other nations, using this as a counterpoint against Russian claims of anti-colonialism. Additionally, developing a systematic approach to leveraging the X platform—particularly in using hashtags and engaging international experts—while maintaining a focus on factual reporting and countering Russian disinformation is crucial.

Key recommendations

To more effectively counter Russian disinformation:

- Counter facts and coordinated strategic communication against the parallel reality and fake news that Russian propaganda seeks to create.

- Track the activities of known pro-Russian "experts" and bloggers and respond to the emergence of new ones, promptly debunking their actions and showing how "neutral" statements contribute to Russian propaganda.

- Continue creating thematic information campaigns with a clear focus (such as the campaign to prevent Russian athletes from participating in the 2024 Olympics and other international competitions).

- Expose instances of cultural expropriation by Russia as evidence of colonialism—when it appropriates the figures and achievements of other nations.

For more effective use of the X platform by Ukrainian diplomats:

- Increase the frequency of posts. Data shows that Russian accounts achieve greater reach partly due to a higher number of posts.

- Use popular hashtags more frequently to appear in platform trends (as Russians do with #OTD).

- More actively involve and retweet international experts and thought leaders who support Ukraine (e.g., the recent thread by billionaire Richard Branson about Putin recruiting North Korean soldiers against Ukraine).

- Adapt messages to the specifics of different countries (such as focusing on food security for African audiences) and local events, like national holidays or achievements of local athletes, to foster positive engagement with local audiences.

- Coordinate content across different diplomatic missions to strengthen the overall informational impact.

- Develop a network of proactive followers who will help spread content through retweets and comments.

Main page illustration and infographic: Natalia Lobach