For a period of two months, the teams at Detector Media and LetsData conducted daily monitoring of news coverage in over three dozen countries with the aim of identifying key messages related to Ukraine and Russian aggression. In this research, we narrow our focus to 11 countries in the Global South, examining the prevalence of pro-Russian and harmful messages that could negatively impact Ukraine.

Українською читайте тут.

The term “Global South” is used by the World Bank to describe low- or middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The Global North is composed of countries with a per capita GDP of more than $15,000, except for Bulgaria and Romania, as they are members of the European Union. Under this definition, both Russia and Ukraine are part of the Global South, along with China and India. However, some geographically southern countries, such as Chile and Uruguay, are classified as part of the Global North due to their higher GDP per capita.

It’s important to note that the Global South is not homogenous, and attitudes toward Russia’s aggression vary significantly in different regions, including Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. While some experts suggest that the Global South has taken a neutral stance on Russia’s war against Ukraine, certain developments suggest a more nuanced picture. For instance, Turkey is trying to play a mediating role in the war by facilitating a grain deal and participating in the exchange of prisoners. Brazil has proposed its own “peace plan” to resolve the military conflict, while China and South Africa conduct joint naval exercises with Russia. Recent public opinion polls in China, Turkey, and India show that people in these countries want the war to end as soon as possible, even if it means Ukraine must make territorial concessions.

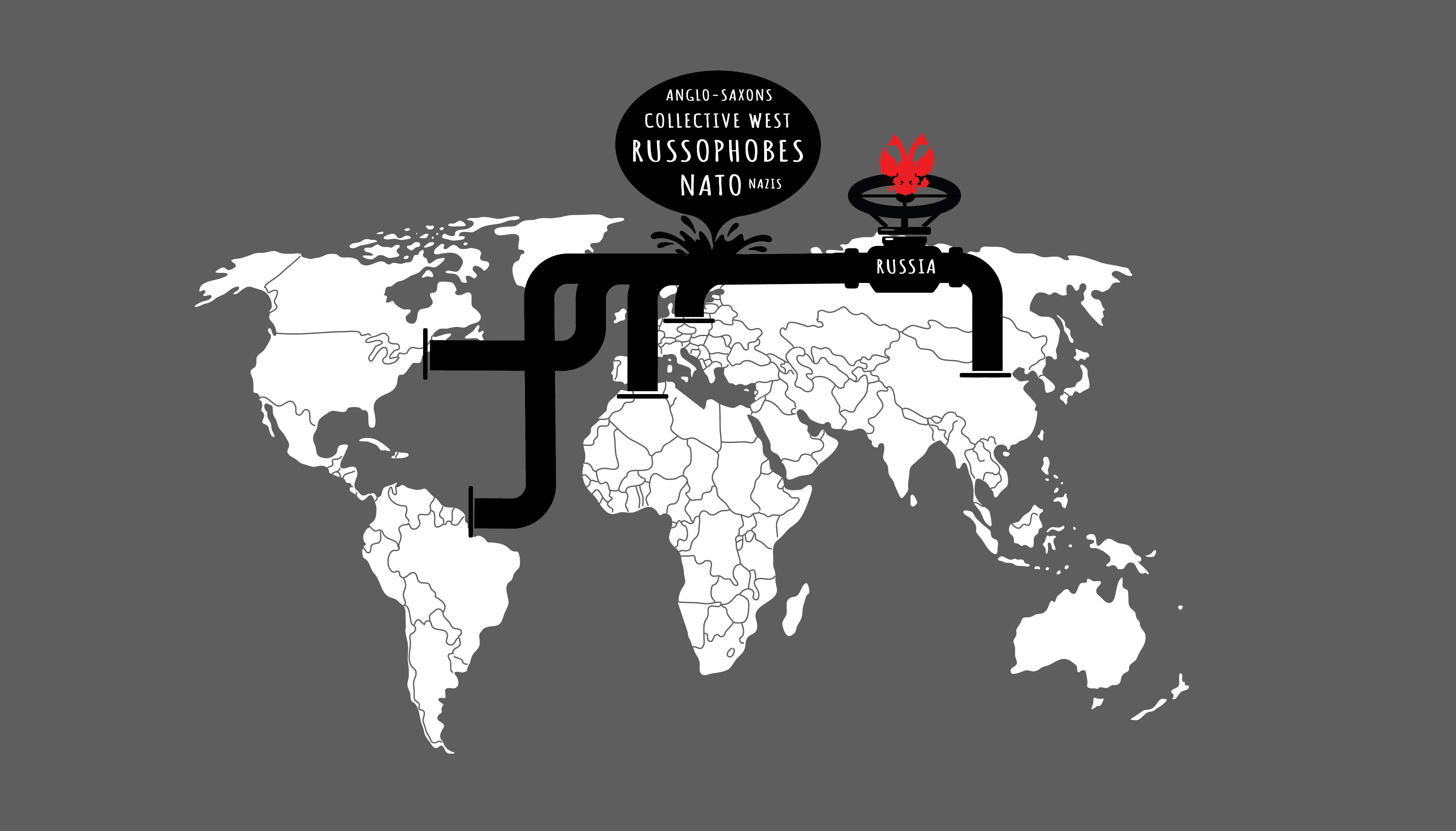

The Global South’s hostility towards NATO, the United States, and international creditors, along with the perception of Russia as a superpower opposing Western hegemony, create a favorable environment for pro-Russian messages to spread in local media. Journalists in the region may uncritically quote Russian officials and neglect Ukraine’s perspective, inadvertently or intentionally echoing the Kremlin’s position. In some cases, the media’s portrayal of Ukraine is distorted, with the country being depicted as a pawn on the global chessboard rather than an independent geopolitical player. The conflict is framed as a confrontation between the US and Russia rather than Russian aggression against Ukraine. By this logic, providing military assistance to Ukraine would only escalate the conflict rather than bring about a peaceful resolution. Additionally, local media may accuse Ukraine of being unwilling to negotiate with Putin and agree to his demands.

Methodology

Between December 19, 2022, and February 22, 2023, LetsData and Media Detector analysts prepared weekly reports on media coverage of Ukraine in 36 countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. To categorize news stories mentioning Ukraine in each country and continent, machine learning and computer data processing tools were employed, analyzing key topics, the mood of the messages, quotes from Russian media, and more. Detector Media used data from LetsData, a company that combines several sources of information about media publications, including Opoint, GoParigon, and SimilarWeb. For each country, all publications related to Ukraine were initially collected, with a reduced sample of 60% of thematic news analyzed in cases where there were numerous reports on Ukraine. News aggregator materials were excluded, as they are often secondary sources that duplicate information from other media outlets already present in the LetsData database.

This text summarizes negative reports about Ukraine from 2,700 of the most popular media outlets in 11 countries in Asia, Africa, and South America. The Asian sample comprises India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, and Turkey. African countries covered in the analysis include Ghana, Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. From South America, the sample includes Brazil and Argentina.

Examining the Content of Toxic Messages in the Region

Argentina’s strong anti-NATO stance is reflected in its media coverage of Ukraine, with toxic messages in the region predominantly based on anti-NATO logic. Such messages suggest that Ukraine is a mere puppet of the West and is not truly interested in achieving peace. Furthermore, the conflict is portrayed as bringing China and Russia closer together while NATO remains a lone player.

Brazil has declared a neutral position on the war against Ukraine, with President Lula da Silva proposing his own “peace plan”, which became one of the central topics in the Brazilian media in February 2023. Brazil is a member of the BRICS organization (a group of the largest developing countries by area and population: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), through which Russia is trying to influence the agenda of the South American region. Brazil is the largest country that imports Russian fertilizers, so the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, sanctions, rising fuel prices, and complicated logistics have had a painful impact on the country’s economy. Local media see this not as a consequence of Russian aggression but as a result of “Ukraine’s unwillingness to seek peace”.

Russian narratives make occasional appearances in Ghana’s media landscape, typically through quotes from Russian officials that are cited in local media.

In Egypt, the pro-Russian discourse in the media is more powerful than the more situational pro-Ukrainian discourse. Russian viewpoints are expressed in quotes from Russian officials who promote messages about the stability of the sanctions-hit economy and the successes of the Russian army.

Indian media frequently emphasizes the country’s neutral stance on the war against Ukraine, reflecting a desire to maintain strong relations with the West while justifying cooperation with Russia based on economic benefits. Moscow remains a key energy partner for New Delhi, and India (also a member of BRICS) is able to avoid joining anti-Russian sanctions while also avoiding any damage to its relationship with the West.

Indonesia’s media discourse is characterized by a neutral stance on Ukraine, but there are discussions about intensifying assistance to Ukraine. President Joko Widodo became the first statesman from the Global South to visit Ukraine during the full-scale war, and Indonesia, as the host of the G20 summit, gave President Zelenskyy the opportunity to present the “Ukrainian formula for peace” for the first time, which was often cited in the local media.

Media coverage of Ukrainian issues in Kazakhstan is characterized by a mix of Russian, pro-Ukrainian, and neutral messages, resulting in a generally ambiguous landscape. Notably, there is a significant proportion of publications that reference Russian media, cite quotes from Russian propagandists and opinion leaders, and espouse a range of anti-NATO and anti-Western messages consistent with the Russian narrative.

In the Kenyan media landscape, Russian officials are frequently quoted, but local media outlets tend to maintain a balanced presentation of opinions in their coverage. Russian statements are often refuted, with the perspectives of Ukraine and Western countries also being presented.

Nigerian media coverage of the conflict in Ukraine tends to emphasize the country’s numerous security challenges, including the Boko Haram terrorist group, Niger Delta militants, clashes between farmers, and Igbo separatism. As such, the media suggests that the West’s support for Ukraine exceeds that of Nigeria.

South Africa’s naval exercises with Russia and China amid the ongoing conflict in Ukraine suggest Moscow’s efforts to advance its agenda in the region through the BRICS organization, of which South Africa is a member. There appears to be a differentiation in the media discourse between the ruling party’s position and the opposition’s stance on supporting Ukraine.

Turkey’s media discourse features an equal presence of pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian messages, with toxic messages often related to Ukrainian missile attacks on Russian troops, alleged threats to Russia’s existence, the deliberate escalation of the conflict by the West, and alleged Russian successes on the battlefield.

The following section takes a closer look at the 23 most common messages in the media landscape of the Global South, grouped into five thematic blocks for convenience.

Block One. Depicting Ukraine as a...

During the analyzed period, characterizations of Ukraine that benefited Russia, including accusations of corruption and adherence to Nazi ideology, were being spread. Such depictions create a demonized image of Ukraine that encourages people to avoid contact with the country, serving the interests of Russian propaganda.

Most Common Negative Characteristics of Ukraine and Ukrainians in 11 Countries in Asia, Africa, and South America

The visualization reflects the number of repetitions of negative messages about Ukraine observed between December 19, 2022, and February 22, 2023, in online media from Argentina, Brazil, Ghana, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey during weekly monitoring of the media landscape of these countries by analysts of Detector Media and LetsData.

“Ukraine Is a Nazi Country”

During our monitoring of publications from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, we observed the proliferation of the Russian disinformation narrative that “Nazis seized power in Ukraine”. In Brazil, for example, media outlets reported that the CIA had organized a “Nazi coup” during the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. Similarly, an Indian outlet went so far as to suggest that “descendants of the Nazis” had taken power in Ukraine after the Orange Revolution in 2004. In both cases, anti-American rhetoric and accusations of the United States supporting “Nazis in Ukraine” were clearly visible. These messages are part of the classic message repertoire of Russian propaganda and have been recorded in Ukraine, Europe, and Russia by Detector Media.

During our monitoring, propaganda articles appeared in the information space of Indonesia and Egypt, accusing Stepan Bandera of collaborating with the Nazis. Media outlets discussed the glorification of Bandera by Ukrainians and Poland’s negative reaction to it.

During the study, we documented reports claiming that “Russia is not at war with the people of Ukraine, but with the Nazis in the Ukrainian government”, and “Russia’s goal is to destroy the Nazi regime”. Most often, these messages were voiced by Russian politicians and diplomats when there was a need to divert attention from the Russians and their war crimes. These messages are frequently voiced in an attempt to shift the responsibility for war crimes to the “Ukrainian Nazis”, particularly in Egypt’s media landscape among the 11 countries analyzed. It is important to note that the tactic of accusing Ukrainians of crimes was used by the Russians to justify their invasion of Ukraine during the first year of full-scale aggression and earlier.

In the media landscapes of Egypt and India, manipulative messages regarding the alleged “harassment of the Hungarian community” have been observed. Against this backdrop, Russian propaganda promotes the narrative that “Ukrainian Nazis” discriminate against all national minorities, particularly Russians.

“Ukraine is a Puppet of the West”

In the media landscape of the Global South, we documented a narrative suggesting that Ukraine lacked agency, merely serving as a Western pawn in the conflict against Russia. Notably, media from Kenya and Egypt frequently echoed Russian assertions that NATO sought to dominate or subjugate Russia using the Ukrainian military. Furthermore, various African and Asian media sources reported allegations that Washington directly commanded Ukrainian authorities to initiate a counter-offensive. Ukrainian citizens were often depicted as victims of the Alliance’s “proxy war” against Russia in propaganda messages. This theme of Ukraine being sacrificed by the West appeared prominently in Kenyan and Turkish media coverage. In Turkey, Russian propaganda advanced the notion that Ukrainians were like “guinea pigs utilized by the United States”, encouraging Ukrainian citizens to resist the Americans rather than the aggressor nation.

We also discovered mentions of additional countries within the context of the “Ukraine as a Western puppet” narrative. In December 2022, Turkish media reported that Putin’s trip to Minsk would undoubtedly result in Belarus launching an assault on Ukraine. By January 2023, the same Turkish outlets alleged that Poland aimed to partition Ukraine. It is important to highlight that claims of Poland intending to invade Ukraine are relatively scarce in the information environment of the examined nations, particularly in comparison to Ukraine, where such reports emerge every few months.

In early February of this year, Brazilian media outlets circulated the notion that the United States intended to economically colonize Ukraine to seize its titanium reserves. These reports suggested that this was the reason behind “America urging Ukraine to launch a counteroffensive and reclaim territory”. In reality, the most significant titanium ore deposits are located in the Volyn, Dnipropetrovsk, and Kirovohrad regions — areas that are not under Russian occupation.

Most often, media sources from Asia, Africa, and Latin America cited prominent Russian figures such as President Vladimir Putin, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Permanent Representative to the UN Vasily Nebenzia, and Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova in their articles, employing highly negative descriptions for Ukraine. These included assertions like “Ukraine is a private military company of NATO” and “Zelenskyy’s gang persists in executing orders originating outside of Ukraine”.

“Ukraine Is a Corrupt State”

Over two months, media outlets in the Global South disseminated messages about corruption in Ukraine, attempting to persuade their audiences against providing military and financial aid to the country.

Specifically, Egyptian media claimed that the Ukrainian military received a mere 15% of the aid, with the remainder allegedly being stolen. During January and February 2023, South African media suggested that weapons from Ukraine could be pilfered or sold at exorbitant prices and subsequently fall into the hands of terrorists and criminal organizations, thereby destabilizing the African region. The Russian propaganda machine disseminated this disinformation as a scare tactic.

A prevailing notion echoed in the Global South, originating from Russia, pertains to the supposed historical continuity and ubiquity of corruption in Ukraine. Nigerian media underscored the “lengthy history of endemic corruption”, while Brazilian sources recalled that Ukraine, once among the wealthiest regions in the USSR, had become “the poorest and most corrupt nation”. Kazakhstani media cautioned that “before supporting Ukraine, it is necessary to remember how corrupt it is”.

We have discussed in more detail how Russian propaganda depicts Ukraine as a “cradle of corruption” here.

“Ukraine Only Harms NATO and the EU”

This narrative was infrequently observed in the media of the Global South. Specifically, Indonesian media reported that the Croatian president denied Ukraine’s right to join the European Union, asserting that Ukraine was not an EU ally. Another example of Russian propaganda promotion came from Ghanaian media, which cited French politician Florian Philippot’s statement that Ukraine would only weaken the EU as a new impoverished and corrupt member. Philippot, formerly the vice president of Marine Le Pen’s National Front party, known for its pro-Russian stance, now leads his own political faction, the Patriots, which expresses strong Euroskepticism. In the 2019 European Parliament elections, the Patriots secured only 0.6% of the vote, preventing Philippot from becoming a member of the parliament.

Broadly speaking, criticism of Ukraine’s aspirations to join the EU and NATO centered on the belief that Ukraine’s membership would allegedly damage these organizations. Russian propaganda employs a wider range of messages concerning Ukraine, the EU, and NATO, including claims that Ukraine has exhausted NATO countries’ arsenals, leaving them defenseless; NATO members being firmly against Ukraine joining the alliance; and the EU rejecting Ukraine’s membership application.

“Refugees From Ukraine are Bad”

In African, Asian, and Latin American media, Ukrainian refugees were often portrayed as a burden on Europe. For instance, this subject appeared multiple times in Ghanaian media, with local journalists asserting that “the period of special treatment for Ukrainian refugees is over”.

These publications employed generalizations and equivocation to emphasize individual (and not always true) situations, presenting them as representative of all Ukrainians. For example, Indonesian media reported that a Ukrainian woman was apprehended in Bulgaria for attempting to smuggle 12 kilograms of gold into the country. Argentine media propagated the message that “Nazi symbols” were discovered in a Ukrainian refugee’s home, suggesting Ukrainians posed a threat to European peace. By disseminating such narratives, Russian propaganda aimed to cultivate a negative image of Ukrainian refugees, discouraging people in other nations from supporting them.

Block Two. Russia Appears Blameless Yet Seemingly Victorious

Pro-Russia messages concerning hostilities against Ukraine can be categorized into two groups. The first encompasses reports claiming that Russia was compelled to initiate the war. The second suggests that Russia is gaining momentum on the battlefield.

Most Common Negative Messages on the War in Ukraine in 11 Countries in Asia, Africa, and South America

The visualization reflects the number of repetitions of negative messages about Ukraine observed between December 19, 2022, and February 22, 2023, in online media from Argentina, Brazil, Ghana, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey during weekly monitoring of the media landscape of these countries by analysts of Detector Media and LetsData.

“Russia’s Successes on the Battlefield”

In a previous study analyzing Russian propaganda in 11 European countries, we discovered that the statement “Ukraine is losing the war” was the most frequent message concerning the full-scale invasion. This trend is also evident in the Global South, where this message ranks among the most repeated. Through this narrative, propaganda seeks to perpetuate the myth of the invincibility of the “world’s second-largest army”, its triumphant advance in eastern Ukraine, the alleged massive losses sustained by the Ukrainian army, and Ukraine’s inevitable defeat.

Media in the Global South closely monitored the progress of Russian forces. For instance, in January 2023, the focus was on events surrounding Soledar, and when Ukrainian troops eventually withdrew from the city, it was portrayed as a devastating defeat for Ukraine. Moreover, several Nigerian media outlets falsely claimed that Russia had occupied the village of Mykolaivka in the Donetsk Region, which remains under Ukrainian control. Reports emphasized that overcrowded Ukrainian hospitals led to numerous soldiers perishing without adequate medical care.

The role of the Wagner PMC in the Bakhmut sector received significant attention. Despite their dubious past, media from Indonesia, Brazil, and Kenya highlighted the effectiveness of Wagner mercenaries and praised their “accomplishments”. Allegedly, they had destroyed NATO tanks (which had yet to be delivered to Ukraine) and skillfully captured new territories.

Media in this region often relayed statements from Russian officials such as President Putin, Chechen leader Kadyrov, Wagner PMC owner Prigozhin, Foreign Minister Lavrov, and Foreign Intelligence Service chief Naryshkin, who issued ultimatums to Zelenskyy, urged him to surrender, and assured him that Russia required only a year to fully occupy Ukraine.

“This Is Not a War Between Russia and Ukraine, but a Conflict Between NATO and Russia”

This narrative surfaced in the media environments of all eleven studied countries. For example, messages suggested that negotiations should involve Washington, not Kyiv, because the United States is the one that has the strongest influence on events. Propaganda statements also claimed that Ukrainians were dying for NATO’s elusive interests, while Russians gave their lives “for their homeland”. Additionally, Russia utilized media in the Global South to accuse the United States of orchestrating a “proxy war” in Ukraine because NATO members supplied weapons to the country. Some media sources claimed that NATO had nearly exhausted its military potential against Russian forces. There were also insinuations that Zelenskyy was drawing NATO into direct conflict with Russia, an action that would undoubtedly lead to the Alliance’s collapse.

Asserting that this conflict is not Russian aggression against Ukraine, but rather Russia’s confrontation with the West elevates Russia’s geopolitical stature (describing a bipolar world) and diminishes Ukraine’s role as a sovereign state, an independent international actor, and a potent force deterring Russian aggression. This message is not exclusive to the Global South; it has infiltrated the media environments of numerous other countries. Simultaneously, it rationalizes Russia’s defeats, arguing that it is warring against multiple powerful states and thus suffering defeats.

Certain states in the Global South believe that the NATO Alliance and the United States impose their will on the rest of the world through military intervention. Consequently, Russian propaganda’s “anti-NATO” and “anti-American” messages successfully build upon existing narratives and resonate within local media environments.

“NATO Is Directly and Indirectly Involved in the War”

Besides the message that the Russian-Ukrainian war is a conflict between NATO and Russia, the propaganda machine disseminates a group of similar arguments. For instance, claiming that NATO conducts regular military training, including cyber training, to prepare for a future attack on Russia. Egyptian media reported that the United States withdrew its troops from Afghanistan allegedly to participate in the war on Ukraine’s side, while Kenyan media claimed that regular units from EU countries have long been fighting alongside the Ukrainian forces. However, the involvement of foreign military personnel in the conflict with Russia is currently an individual decision by soldiers, and units from other countries’ armed forces are not engaged in hostilities. Moreover, toxic messages in the region argued that NATO’s involvement only fueled the war and risked unprecedented escalation.

“The West wants to use Russian aggression to attack Russian territory, even if it is done through the Ukrainians”, is another “anti-NATO” message disseminated in the region’s media, particularly in Brazil. Allegedly, NATO wages a hybrid war against Russia by accepting new members into the organization, provoking the Kremlin to respond directly with military force.

Such rhetoric is extensively employed by Russian propaganda to shift the blame for the war against Ukraine onto NATO as if Russia was forced to react to the organization’s “expansionist” policy.

“The West Benefits From War”

During the two-month monitoring period, Indian media were spreading the message that the West benefits from the war because it exhausts Russia. The argument is that afterward, it will be easy to destroy Russia and establish a unipolar political system with a single hegemon in the form of the US/NATO. Additionally, Egyptian media called the United States the key beneficiary of the war. Indonesian media asserted that the West had an opportunity to dispose of old weapons and upgrade its military capabilities. In the Kazakh media environment, there was an opinion that the war presented a chance to redistribute the energy market (through sanctions against Russia), so the West would attempt to fuel the war in every way possible to cut off markets for Russian gas and oil. With such accusations, the Russians aim to deflect attention from their aggression and place the blame on those who oppose it.

This message also aligns with the paradigm of anti-Western sentiment in the region. It discourages the states of the Global South to become more actively involved in helping Ukraine, as it portrays the war as a matter of two superpowers (the United States and Russia) rather than a struggle for freedom and values by Ukrainians.

“The West Is Provoking Putin to Start a Nuclear War”

This message somewhat overlaps with the message about the risk of the war spreading beyond Ukraine. It claims that the West is crossing “red lines” and irritating Putin in every possible way, provoking him to use nuclear weapons. The West’s active military assistance and support for Ukraine allegedly provide Russia with a justification for a nuclear strike.

As early as March 2022, Russia promoted the topic of ballistic nuclear missiles, then the use of tactical nuclear weapons, followed by threats against the Chornobyl and Zaporizhzhia NPPs. All of this constitutes blackmail aimed at forcing Ukraine to negotiate on unequal terms and the world to withdraw its support for Ukraine.

Block Three. Russians Accuse Others of Crimes and Russophobia

The media of 11 countries studied broadcast the positions of Russian representatives as newsworthy. For instance, the information environments of Asia, Africa, and South America are being infiltrated by reports that Russian crimes are fabricated and that supporting sanctions against Russia is unjustified.

Most Common Accusations of Russia’s Supporters Against Ukraine and Its Partners in 11 Countries in Asia, Africa, and South America

The visualization reflects the number of repetitions of negative messages about Ukraine observed between December 19, 2022, and February 22, 2023, in online media from Argentina, Brazil, Ghana, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey during weekly monitoring of the media landscape of these countries by analysts of Detector Media and LetsData.

“Western media are lying”

Russian propaganda occasionally accuses Ukraine and its partners of lying. Open allegations of lies by Western media were propagated in Turkey and Egypt, with the United States being accused of spreading fake news about Russia. Nigerian media broadcast the message that Facebook had blocked the largest Russian-language media account of the propaganda resource Russia Today, allegedly without explanation. Kazakhstani media claimed that the ban on Russian media would lead Europeans to be unable to “learn the truth about war-torn Ukraine”.

The grain initiative was another supplier of false messages that aligned with Russian propaganda. For instance, Turkish media, quoting Recep Erdoğan, claimed that half of the grain imported from Ukraine, which was supposed to go to the poorest countries, ended up in Europe.

Kazakhstani media insinuated that Western media constantly lie, while Russian media tell only the truth and take into account the interests of the poorest and those to be colonized. In reality, even if Russian media reports resonate with the views of some consumers outside Russia, it does not mean that Russia itself does not pursue a colonial policy.

“Ukrainians Commits War Crimes”

Emotionally charged messages claiming that Ukrainians are committing war crimes have appeared in Asian, African, and Latin American media. Through this, the aggressor country attempts to influence local public opinion and persuade them that it is not the Russian army committing atrocities but the Ukrainian military.

Numerous disinformation messages revolved around Ukraine’s alleged attacks on civilian targets in Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia regions. Article headlines often included the supposed number of people killed. Regarding the victims, propagandists’ rhetoric mainly focused on the term “civilians”. Indonesian media also emphasized the word “children”, claiming that Ukrainian troops killed a ten-month-old child during a bombing. Another topic concerned the alleged killing of Russian prisoners by the Ukrainian army. These messages were frequently disseminated in Indonesian media and coincided with the accusations that Russia was deporting Ukrainians. It is worth noting that, since the end of March, Vladimir Putin and Russian Presidential Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova have been on the international wanted list on charges of facilitating the war crime of deporting civilians.

Among the messages about victims of “Ukrainian war crimes”, we found claims of “attacks on Russian journalists”, an attempted assassination of a Russian army military commander, and an attempt to kill the head of Roscosmos during a Ukrainian attack.

In almost all propaganda messages from Asia, Africa, and Latin America that we analyzed, Western allies are portrayed as Ukraine’s “ puppet masters”. The articles constantly emphasize terms like “NATO missiles”, “American weapons”, “NATO ammunition”, and so on. Ukraine was also accused of trying to trigger a nuclear catastrophe, as it allegedly fired HIMARS missiles at the Zaporizhzhia NPP.

“Enemies Fabricate Russian Crimes”

Detector Media has previously reported on the tactics employed by the Russian propaganda machine during the Ukrainian counteroffensive. One of the most important is statements about the alleged “fabrication of crimes committed by the Russian army”, which the aggressor country makes mostly after or before Ukraine achieves military success. We found similar messages in the media of the Global South.

Egyptian, Indian, and Brazilian media outlets repeated the message that Russia was not involved in the missile attack on a residential building in Dnipro on January 14, 2023. The media in the analyzed countries claimed, citing Russian politicians, that the aggressor country did not attack civilian targets at all and that the Dnipro apartment building was hit by a Ukrainian air defense missile.

In Kazakhstan and Egypt, fake news circulated claiming that SBU officers dug up graves on Christmas Eve, mutilated exhumed bodies, and dumped them into pre-dug trenches. All of this was allegedly done to fabricate crimes committed by Russians, create an untruthful narrative, and ask Western allies for long-range missiles. One Egyptian media outlet even named these “SBU actions” Operation Phantom. Additionally, Turkish and Egyptian media disseminated disinformation claiming that Ukraine had set fire to grain warehouses in Kherson to blame Russia.

In the Global South’s media landscape, discussions surrounding the 2014 downing of MH17 by the Russians have resurfaced. Initially, Russia had placed the blame on Ukraine, but the European Court of Human Rights later determined that two Russian nationals and one Ukrainian national had employed a Buk missile and anti-aircraft system against the civilian aircraft, with Russia maintaining control over the part of the Donetsk region where the Buk was launched. Brazilian media highlighted the Kremlin’s denial of any involvement in the incident, while South African media headlines emphasized the assertion that Putin himself was not implicated in the attack.

“Russophobes Want Russia to Suffer”

In our analysis of the information landscape across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, we observed Russian propaganda messages centered around “Russophobia”. These messages are utilized by Russia to justify its own malicious disinformation campaigns against Ukrainians, the “collective West”, Georgians, Japanese, and numerous other groups.

Among the most prevalent were accounts of supposed repression against the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP). Specifically, Egyptian media asserted that Ukrainian authorities intended to “demolish the Orthodox Church” and labeled President Zelenskyy’s decision to revoke the citizenship of 13 UOC-MP priests as “malevolent”. Nigerian media outlets described representatives of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine as “unordained, rich individuals”, claiming their service “at the sacred Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra would be a profound disgrace for all of Ukraine”. Kazakhstan’s media expressed such concern for the UOC-MP’s fate in Ukraine that they reported numerous searches, raids, arrests, and property confiscations involving representatives of this religious organization, concluding that “Ukraine has obliterated the entire Orthodox Church within the nation”.

The study also included allegations of Russophobia directed at the United States, Japan, and the “collective West”. In these articles, pro-Russian experts warned of harsh retribution for all those who “harbor hatred and seek Russia’s destruction”.

Media in Nigeria, Brazil, and India conveyed messages about Ukraine’s alleged discrimination against Russian-speaking citizens. Turkish media coverage suggested that the Russian-Ukrainian war represents “a clash between two siblings, members of the same nation slaying one another while wearing the uniforms of different armies”. A comparable propaganda narrative, claiming that “Russians and Ukrainians share common historical roots, as both countries were constituents of the Soviet Union”, surfaced in Indonesian media. This oversimplified view of Ukraine’s history aligns with the Russian elite’s stance that Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians are one people, a notion that Vladimir Putin reiterated, among other instances, prior to his invasion of Ukraine. In reality, both nations were “part of the USSR” because Russia occupied Ukraine in the early 20th century.

Block Four. Sanctions Harm Everyone but Russia

“Sanctions bolster Russia’s sovereignty”, “Russia adeptly evades sanctions”, and “In 2022, Russia emerged as the most economically stable G20 nation” are common narratives asserting Russia’s resilience to sanctions imposed following the invasion of Ukraine. Employing similar language and citing unverifiable figures from Russia’s official statistics, propagandists attempt to counter the compelling evidence that sanctions are significantly impacting Russia. International corporations are leaving the country, and former key partners, such as European nations, have ceased purchasing Russian goods and energy resources.

To advocate for Russia’s continued appeal to foreign businesses, Russian sources reference their own internal data, stating that a mere 8.5% of international companies have departed. Assertions regarding the loss of the European market are countered with claims that Europeans suffer more than Russians. This message has been echoed repeatedly in the previously examined region of Central and Eastern Europe.

Most Common Reports About Russia’s Economic and Geopolitical Influence in 11 Countries in Asia, Africa, and South America

The visualization reflects the number of repetitions of negative messages about Ukraine observed between December 19, 2022, and February 22, 2023, in online media from Argentina, Brazil, Ghana, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey during weekly monitoring of the media landscape of these countries by analysts of Detector Media and LetsData.

Kremlin propaganda permeates the media landscapes of Asia, Africa, and South America, contending that the European economy endures greater damage from sanctions than Russia itself. These messages reference European countries’ statistics, such as Germany’s loss of 100 billion euros during the year-long imposition of sanctions on Russia. Reports also suggest that Germany, grappling with an energy crisis without Russian gas, is clandestinely requesting oil from Russia’s Transneft.

The context of European countries refusing Russian goods and services in response to the invasion of Ukraine and Russia’s numerous breaches of international law is typically ignored.

“Russia Should Participate in Sports Competitions”

Russian propagandists exploit sports-related topics to justify the aggressive war waged by Russia against Ukraine. The propaganda machine depicts Russians’ efforts to rejoin major sports events as “an attempt to overcome Russophobia and discrimination”, while it actually serves to legitimize the aggressor.

Sports-centered propaganda has also emerged in African, Asian, and Latin American media. The majority of messages pertain to Russia’s potential inclusion in the 2024 Olympics and feature quotes from the International Olympic Committee. South African media has reported that “any attempts to exclude Russia from world sport will be quashed” and that Russian athletes are suffering from their inability to compete in international events.

Block Five. Do Not Help Ukraine

Most Common Arguments Against Aid to Ukraine in 11 Countries in Asia, Africa, and South America

The visualization reflects the number of repetitions of negative messages about Ukraine observed between December 19, 2022, and February 22, 2023, in online media from Argentina, Brazil, Ghana, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey during weekly monitoring of the media landscape of these countries by analysts of Detector Media and LetsData.

“We Should Not Give Weapons to Ukraine”

The topic of weapon supplies to Ukraine has garnered significant attention in the media of the Global South. Our research coincided with the active formation of the “tank coalition”: in January 2023, Germany announced its plans to supply Ukraine with Leopard-2 tanks and permit other nations to export German tanks. Concurrently, the contact group on military assistance to Ukraine frequently met in the Ramstein format, and Western partners actively debated providing military aircraft to Ukraine.

In an attempt to deter the West from ultimately supplying Ukraine with substantial quantities of heavy weaponry, Russian propaganda resorted to disseminating discrediting messages that reverberated in the Global South’s media landscape.

For instance, claims were made that tanks and fighter jets would only prolong the war, making it unlikely for Western partners to take such action. Additionally, even if the latest weapons were supplied to Kyiv, it was argued that Russian forces would promptly destroy them. Messages also suggested that the tanks allies intended to provide Ukraine would not significantly change the battlefield, given Russia’s overwhelming arsenal. Furthermore, it was posited that if the West continued to flood Ukraine with weapons, it would ultimately be left defenseless and vulnerable. These messages were prevalent in all countries of the region.

It is worth noting that in January 2023, when Ukraine and several allies requested military aid from Latin American countries, these nations categorically refused to supply Kyiv with weapons previously purchased from Russia, even in exchange for cutting-edge, American-style weaponry.

“Ukraine Does Not Want Peace”

This toxic message frequently appears in the media of the Global South, irrespective of the specific country. Zelenskyy’s visits to the United States and Europe, his continuous requests for weapons, and his rejection of China and Brazil’s “peace plans” were all portrayed as Ukraine’s unwillingness to pursue a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Additionally, the Global South’s media often underscored Putin’s purported receptiveness to dialogue and his supposed first conciliatory step: announcing a ceasefire during the Christmas holidays. According to these reports, Russian forces would halt their attacks on Orthodox Christmas Eve, but Ukrainian troops would not.

Some messages even suggested that Ukraine could have ceded the territories that allegedly historically belonged to Russia. For instance, Brazilian media, echoing the official stance of President Lula da Silva, proposed ceding Crimea to Russia, which was expected to appease the aggressor.

In presenting such arguments, the Global South’s media overlooks an alternative perspective: conceding territory would not actually end the war but rather intensify it. Russia would not abandon its primary objective of conquering Ukraine, and any compromises would be interpreted as a reward and validation of the Kremlin’s strategy. Accepting peace on Putin’s terms would only embolden him further.

“The Risk of the Conflict Spreading Beyond Ukraine”

Apart from the notion that NATO is already directly or indirectly involved in the war, the idea of potential hostilities erupting in Ukraine’s neighboring countries gained traction. For example, Turkish media accused Kyiv of allegedly pulling Tbilisi into the conflict, while Egyptian media claimed Ukraine was drawing Moldova into the fray, denying any Russian coup preparations. Kazakhstani media reported that Poland was already gearing up for war and mobilizing (we had refuted this fake). The argument that supplying weapons to Ukraine only heightens the risk of expanding the scope of hostilities was also widely repeated.

Russia employs such rhetoric to compel the West to engage in protracted debates about military aid to Ukraine and to delay its delivery.

“The West Is Getting Tired of Ukraine”

In the media of Kenya, India, and Indonesia, more frequently than in other countries studied, a narrative emerged emphasizing the growing fatigue and frustration among those who have been observing the war since 2014. For nine years, Russian propaganda has employed this argument to cast doubt on the necessity and effectiveness of continuing support for Ukraine in its fight against foreign aggression.

Key messages include: waning support from the West as governments prioritize their own citizens’ welfare over someone else’s war; public opposition to increasing military aid for Ukraine; and the war fostering discord between the US and the EU due to differing opinions on aid to Ukraine. For instance, reports of a 13,000-strong “pacifist” rally in Berlin following the Munich Security Conference in February 2023 appeared in all analyzed countries.

These messages are easily manipulated and employed against Ukraine. Even readers without personal animosity toward Ukraine may resonate with assertions that governments should address domestic issues (poverty, unemployment, inflation) rather than engage in geopolitical games, potentially leading to “Ukraine fatigue”.

Moreover, news of preferential treatment for Ukraine also sparks discontent in the Global South’s media. For example, criticism emerged when a group of Ukraine’s creditors agreed to postpone debt payments under the International Monetary Fund program until 2027, as Argentina and Egypt are currently the largest IMF debtors.

It’s Not That Simple: Conspiracy Theories as Tools for Propaganda

The analyzed materials revealed instances of conspiracy theories used to foster distrust toward Ukraine and the actual events of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Specifically, Indian media claimed that Putin allegedly vowed not to kill Volodymyr Zelenskyy, which supposedly prompted the Ukrainian president to remain in the capital during the early stages of the full-scale war and record “daring videos”. Indian and Kazakhstani media reported this conspiracy theory, citing former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s words. Similar messages in Kazakhstani media suggested that Zelenskyy feared his own army and thus created a special guard force under his control.

Media in India, Turkey, Indonesia, and Egypt disseminated disinformation about US biological laboratories in Ukraine. Messages alleged that the US trained Ukrainians to create biological weapons intended for use against Russia, while some reports maintained that the US had relocated its biological research labs from Ukraine to Central and Eastern Europe. Indian, Turkish, and Egyptian media also spread fake news about Ukraine deploying chemical weapons against the Russian army, supposedly dispersed via drones. It is worth noting that the narrative about American biolabs in Ukraine gained the most traction in the initial months following Russia’s full-scale invasion but still resurfaces occasionally.

Additionally, an unusual conspiracy theory reported by Kenyan media suggested that Volodymyr Zelenskyy would remain in the US after his visit because he owns a house in Florida.

Global South: A Russian Ally?

The media landscapes in the analyzed countries periodically propagate the notion that the majority of the world’s population does not support sanctions against Russia. According to Russian propagandists’ model of the world, those who support Russia live in the countries of Africa, Asia, and South America. Russian propagandists portray these “Global South” states as opposing Europe and North America. This view is held not only by Russian citizens but also by some local experts and politicians.

However, according to Ukraine’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Japan, Serhii Korsunskyi, the concept of the Global South and the “global majority” is more rhetorical than real. After all, among the countries that are among the twenty richest and have a great influence on the global economy and politics are “southern” Japan, China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa.

“China, India, and other countries that Russia considers to be the ‘majority’ need order, and they are participating in its creation. There is no denying the fact that globalization has opened up unprecedented growth opportunities for the countries of East and Southeast Asia. In terms of GDP growth rates, even in the year 2022, the first nine places in the world are occupied by the countries of the Global South”, emphasized Serhii Korsunskyi.

Nevertheless, countries in Asia, Africa, and South America sometimes benefit from collaborating with Russia and delaying sanctions against it. Turkish media, in mid-January, detailed the advantages of India and China cooperating with Russia to oust US influence in Asia and the global economy.

The arguments in favor of supporting Russia may differ from country to country in the Global South. For instance, in Ghana, Russian diplomats claim that Russia comprehends the continent’s issues better than Europeans or Americans, who view Africa as purely exotic. African nations also discuss the advantages for those states that continue to purchase Russian arms (like Eritrea), grain and oil (such as Mali), participate in joint military exercises (like South Africa), or maintain joint investments (as Egypt does).

In Asia and Latin America, Russian and pro-Russian advocates persuade residents to oppose sanctions by emphasizing the economic benefits of sustained trade, despite international sanctions and the UN General Assembly’s denunciation of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

Occasionally, Ukraine’s reluctance to concede to Russia is used to rationalize problems in other countries. For example, in mid-January, Argentina reported that protests in Peru and the fall of the Peruvian Sol exchange rate were a result of the war in Ukraine, limitations on grain exports, and Russian energy resources. In reality, the protests in Peru stemmed from a conflict between President Pedro Castillo and the nation’s parliament.

As Russian propaganda targets Asian, African, and South American countries, the messages align with the official stances of India, South Africa, and Brazil, which abstain from endorsing UN General Assembly resolutions supporting Ukraine’s territorial integrity or condemning Russia. This implies that Ukraine’s strategic communications sector and diplomats will need to make significant efforts to shift perspectives on Ukraine.

Conclusions

Russia’s reputation as a leader in employing disinformation and manipulative campaigns is not unfounded. Research from Princeton University reveals that the Kremlin accounts for 62% of meddling in other nations’ internal affairs. Russia’s system of disinformation and manipulation has penetrated the information space of different continents and has been operating for many years. The full-scale war against Ukraine merely highlights the deep entrenchment of propaganda messages in numerous countries’ media.

This disinformation campaign aims to erode the legitimacy of Ukrainian statehood and trust in its political institutions, devalue Ukraine’s resistance and Euro-Atlantic ambitions, and foster belief in Russia’s narrative. Russian disinformation adeptly resonates with the local context of specific regions, contributing to a pro-Russian geopolitical orientation.

Based on our research findings, the media landscape in 11 countries predominantly upholds the notion that any entity opposing the West, including Russia, is an ally of the Global South. The Kremlin has skillfully exploited this postcolonial perspective, framing the invasion of Ukraine as a response to the “expansionist intervention of the West”.

Discussions in the Global South’s media about the Russian invasion often scarcely mention Ukraine, focusing instead on broader topics such as Western colonialism, trade wars, sanctions, globalization, and other wide-ranging geopolitical issues. Moscow merely adapts these “ambiguous” subjects to its propaganda goals, asserting that Ukraine is not a victim of Russian aggression but a battleground between Russia and NATO. This approach risks diminishing Ukraine’s significance in its own defense and undermining its agency in geopolitics and international relations.

Ukraine has yet to successfully counter Russia’s upper hand in the narrative battle within most Global South countries. However, when it comes to colonialism, Ukraine shares more common ground with the Global South than Russia does. Ukraine could present Russian aggression for what it truly is — an attempt to dismantle a century of international law achievements and resurrect colonialism in the 21st century.