Українською читайте тут.

As per the V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, democracy levels have regressed to those of 1986 in recent decades. By 2022, approximately 72% of the global population, or 5.7 billion individuals, are living under autocratic governance. For the first time in over twenty years, closed autocracies have outnumbered liberal democracies. Russia's invasion of Ukraine serves as a clear instance of autocratic regimes directly assaulting democracy.

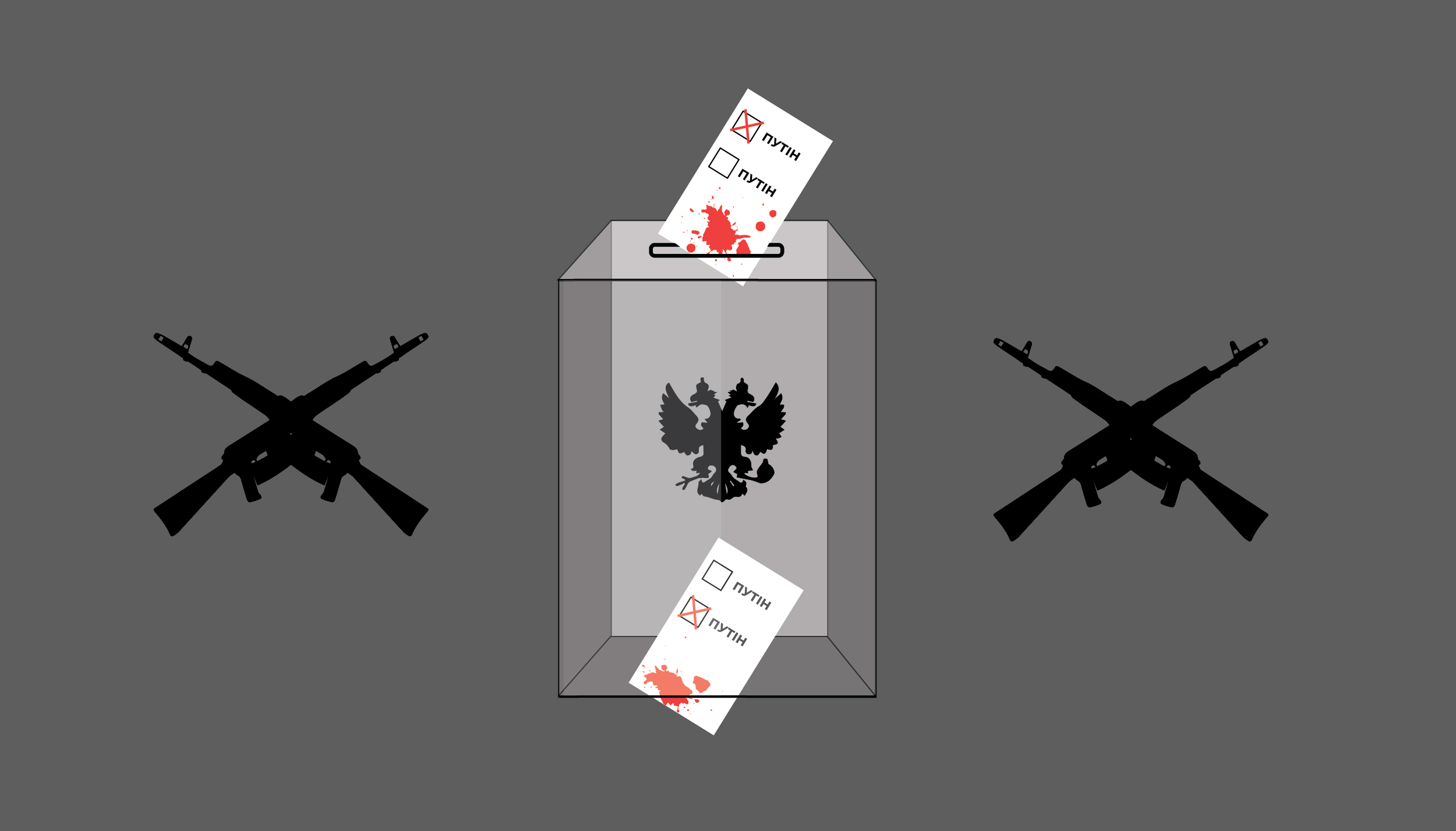

Almost all autocracies worldwide, with the exception of five nations—the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the State of Qatar, the Sultanate of Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Vatican City (which is occasionally categorized as an autocracy)—have conducted elections since 2000. Additionally, nearly three-quarters of these autocracies have purportedly experienced multi-party contests. Nonetheless, scholars frequently label such regimes as "electoral autocracies." Despite their imitation of democratic structures, these regimes persist as authoritarian due to their elections failing to meet established standards of freedom, democracy, and openness. Notable examples of electoral autocracies include Russia, Belarus, Singapore, Jordan, and Venezuela.

Authoritarian leaders often shift blame onto the West for the absence of democracy. In the autumn of 2022, during Russia's staged referendums and forceful annexation of Ukrainian territories, Putin accused the West of pursuing a neo-colonial policy of apartheid and despotism, contrasting it with Russia's purported delivery of genuine democracy to the people. However, simultaneously, he utilizes democratic facades to bolster dictatorship and suppress opposition.

Within the Russian context, the "opposition" primarily serves to maintain the illusion of political diversity while effectively sidelining critics of the regime. Public figures in Russia who challenge Putin's rule face physical harm, marginalization, or forced exile. Consequently, the ruling party and the president evade genuine competition, denying voters even a theoretical opportunity to choose an alternative political agenda.

This discussion regards Russia as an electoral autocracy, examining how severely compromised the electoral process has become under Putin's leadership.

Why do authoritarian regimes hold elections?

In autocratic regimes, voting is often framed not as a right but as a civic duty, symbolizing loyalty to the ruling regime. Consequently, a high voter turnout is frequently interpreted as widespread public endorsement of the regime, even in the absence of genuine competition or alternative programs in elections. Particularly in personalized (presidential) elections, a high turnout becomes almost obligatory and serves as a de facto "vote of confidence" in the regime.

For instance, in Belarus, presidential election turnouts have consistently remained above 83-84% since 2001, according to the Belarusian Central Election Commission. This high turnout, reminiscent of military dictatorships in African countries, has consistently reaffirmed support for President Oleksandr Lukashenko, reflecting perceived loyalty to his leadership.

Additionally, during the Soviet era, voter turnout routinely exceeded 90%. According to Alexei Yurchak, a Russian-American anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley, a significant portion of the population participated in mass demonstrations organized by Soviet authorities, were members of trade unions and communist organizations, and engaged in ideological practices of the system. For example, in the early 1980s, approximately 90% of all high school graduates in the Soviet Union were members of the Komsomol (Young Communist League), and the total number of Komsomol members exceeded 40 million, in a population of around 280 million. Furthermore, as of January 1, 1989, the Communist Party of the USSR had over 19 million members. This widespread participation underscored the ideological conformity and apparent support for the regime.

Under the guise of democracy, autocrats often engage in mimicry, utilizing elections to convey to both domestic and international audiences the illusion of a renewed "popular mandate." They argue that this isn't self-aggrandizement or power usurpation but rather an emulation of democratic processes and the faithful execution of constitutional mandates. The dictator hopes that by doing so, they can mitigate to some extent the negative perception of authoritarianism that surrounds their rule.

Moreover, merely holding elections or superficially adhering to electoral procedures can serve as a prerequisite for participation in international organizations. A prime example of this dynamic is the relationship between Russia and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Since joining PACE in 1996 and subsequent expulsion following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia has navigated various phases of interaction with PACE. This journey ranged from ratifying the European Convention on Human Rights in 1998 to the suspension of Russia's voting rights after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and eventually to the restoration of these rights in 2019, despite contentious debate within PACE regarding the organization's commitment to defending human rights and democratic principles.

In a significant development, PACE became the first international organization in October 2022 to classify the Russian regime as a terrorist entity, highlighting the ongoing complexities surrounding the intersection of authoritarianism, democracy, and international relations.

Testing local elites for strength. The autocrat relies on the support of the so-called selectorate (from the English select — to choose), he is not interested in the opinion and position of the majority of voters. In non-democratic regimes, those who are ready to support the government for personal benefits (money, career opportunities, or even the absence of repression against them directly) are called "selectorate". It is precisely this type of "voters" that the ruling regime asks for its own political preservation and reproduction. Instead, in democracies, politicians are forced to promise to improve the access or quality of public goods (implementing reforms, changing taxes, affordability of health insurance, etc.), appealing to the widest range of voters. Under the model of electoral autocracy, elections turn into a peculiar rite of nomenclature initiation (in the words of political analyst Kateryna Kurbangaleeva), testing the "selectorate" for its ability to conserve the status quo and thus strengthen and reproduce the power of an unchanging leader. During the election campaign, the autocrat's proteges pretend to be medieval feudal lords controlling their "allotments", ensuring appropriate turnout and voting results. In the post-Soviet space, an example can be given of the influence of the so-called red directors — heads of enterprises, especially in monocities with the dominance of one economic sector, on the instructions of which workers' families are forced to vote. The presence of competition and confrontation between different groups of elites can be perceived as a weakness of the head of the region, unable to bring order in his "patrimony".

Loyalty check. The stability of authoritarian regimes is based on the support of the "selectorate" and the loyalty of the "security forces". This type of support is extremely unstable, as it is tied not only to the relevant political cycles, but also to the control of access to resources, depends on the health or even the mood of the leader, etc. Struggles for access to resources and "loyalty checks" can lead to social upheavals such as attempted coups, revolutions, and mass political persecution. In this model, elections are often a "safety valve" for threat management. Such elections offer autocratic presidents a "dignified" way to remove strong popular supporters who might pose a threat (even if their staunch loyalty has never been in doubt) and reshuffle cabinet ministers. This can give the public the illusion that a reset is taking place and that economic problems are to be blamed solely on ousted ministers or lower-level managers, rather than the president. At the same time, the apparent admission of "opposition" candidates can help identify those disloyal to the regime. The most recent example is Putin's upcoming election, when the so-called opposition candidate Boris Nadezhdin was barred from the election due to an extremely active campaign to collect signatures. Instead, Kremlin propagandist Volodymyr Solovyov, on the contrary, publicly thanked Nadezhdin allegedly for collecting data on "enemies of the people": "He brought a list of unscrupulous agents of influence, enemies of the people, PsyOp bookmarks, uneradicated "swarms." That is, he did a lot of work: he isolated, collected all their personal data and gave it to the competent authorities for study."

Elections “vnie politiki” (beyond politics)

In 2021, Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of the Russian State Duma, claimed that Russia possesses a unique "democracy gene" ingrained in its history—a supposed legacy of popular self-governance and parliamentary tradition spanning centuries. However, in practice, this notion of "democracy" in Russia translates into the perpetuation of one dictator's power, the consolidation of authoritarian control, and the suppression of alternative voices. Propagandists have coined the term "sovereign democracy," popularized by former Kremlin official Vladislav Surkov, to justify this authoritarian rule.

Dmitry Peskov, the press secretary of the Russian leader, has staunchly defended this version of "democracy," proclaiming it as the best and vowing to continue its development: "We will no longer entertain criticism of our democracy or claims that it falls short. Our democracy is unparalleled, and we are committed to its advancement." Under this political regime, elections have been reduced to mere formalities, establishing a de facto one-party system where all state institutions serve as tools of the Kremlin.

The Putin regime maintains its grip on power through strategies such as depoliticization and the curtailment of fundamental civil rights, including freedom of political association, assembly, and expression. Opposition voices often refrain from participating in elections due to the absence of genuine choices on the ballot, which are typically dominated by pro-government or technical candidates. Despite this, the authoritarian system instills a sense of civic duty to vote, fostering the illusion of popular participation while ultimately maintaining the status quo.

In the context of Russian politics, the political aspect has been so diluted that elections, paradoxically, have become devoid of any genuine political significance. Rather than serving as a platform for competing political ideologies or figures, elections reflect the near-complete depoliticization of public life in Russia. For the majority of Russians, who are politically indifferent, participation in elections is simply another way of disengaging from politics altogether. Voting is no longer seen as an act of active citizenship or a mechanism for effecting real political change; instead, it is perceived as a means of maintaining the status quo—an "apolitical" system under Putin's unchallenged rule.

In exchange for participating in such elections, the selectorate is promised "stability," superficial improvements such as cosmetic upgrades to schools before the next round of elections, higher pensions, or conditional benefits like preferential mortgage rates. This depoliticization is evident in the selection of presidential candidates, who primarily serve a technical role and avoid engaging with critical political issues, effectively legitimizing Vladimir Putin's rhetoric without challenge.

In Russia's system of "managed democracy," the parliamentary opposition primarily serves to create the illusion of political diversity while carefully excluding most critics of the regime. Presidential candidates are typically handpicked and groomed by the authorities, resulting in a lack of genuine competition in election campaigns. These candidates, often referred to as "technical candidates," avoid discussing sensitive political issues and refrain from questioning obedience to Putin, the interests of the ruling elite, or the authority of the government. For instance, during the 2019 elections to the Moscow City Duma, not a single candidate from the "democratic opposition" managed to secure a spot on the electoral lists. Opposition politicians proposed various strategies for voters during the voting process. Alexei Navalny advocated for "smart voting," suggesting that voters should support candidates who have the best chance of defeating the "pro-government" opponent. Mikhail Khodorkovsky encouraged voters to only support worthy candidates, and if none were available, to spoil the ballot with slogans such as "Freedom for political prisoners!" or "Down with autocracy!". Dmitry Gudkov called for the creation of public lists of acceptable candidates, while Gary Kasparov urged Russians to boycott the elections altogether.

In electoral autocracies, conducting elections serves multiple purposes: it signals to both supporters who are willing to be co-opted into the ruling system and opponents who may face further repression. A strong showing of support for the regime often emboldens authorities to intensify their crackdown on dissent. Following elections, there are typically reshuffles within the hierarchical management structure under the dictator's control, or reorganization of security agencies aimed at intimidating real and potential opponents. Elections enable the regime to assess the strength of its opposition and gather valuable intelligence on dissenting factions. Moreover, the apparent adherence to election procedures, despite their often superficial nature, sends a signal to the international community. It provides a semblance of legitimacy and serves as a basis for the formal recognition (or non-recognition) of power by international organizations and foreign governments. Paradoxically, in autocratic regimes, elections can inadvertently perpetuate dictatorship by providing a veneer of legitimacy to authoritarian rulers.