Українською читайте тут.

Since at least March 2024, Russian propaganda has been spreading a manipulative message claiming that upon completing his 5-year term in office on May 21, Volodymyr Zelenskyy allegedly loses his legitimacy as president. This has been detailed by Detector Media in the articles Witnesses of Zelenskyy’s Illegitimacy and Legitimacy Vacuum. This manipulation has now taken on a new dimension — Putin not only questions the legitimacy of the Ukrainian president but also asserts that power should supposedly transfer to the Verkhovna Rada and its Chairman, Ruslan Stefanchuk, allegedly as required by the Ukrainian Constitution. This is not the first instance where the Kremlin has attempted to interpret the supreme law of our country. Here, we explore the connections between the “third round” of the 2004 presidential elections, Oleksandr Turchynov, the unitary status of Ukraine, and Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Additionally, we examine how propaganda distorts legal and political reality through constitutional casuistry.

Constitutional Turbulence of the 2000s

The Constitution of Ukraine was adopted in 1996, and it was in connection with the 2004 presidential elections that manipulations with the supreme law began. At that time, Moscow made every effort to ensure that power in Kyiv was in the hands of someone loyal to the Kremlin and that Ukrainian statehood and the rule of law did not strengthen. There were Ukrainian politicians who, either knowingly or unknowingly, played along with these Russian interests.

In late 2003, the Constitutional Court made a historic decision regarding the terms of the President of Ukraine’s office. Leonid Kuchma was elected in direct elections in 1994 and 1999, with his second term ending in the fall of 2004. The Constitutional Court gave him the green light to run for a third term despite the law prohibiting one person from serving as President of Ukraine for more than two consecutive terms.

Traitor Viktor Medvedchuk, who was then head of Kuchma’s presidential administration, stated back then that this Constitutional Court decision was legally flawless, arguing it was part of constitutional reform and a departure from Soviet authoritarianism. In the summer of 2004, the publication Ukrainska Pravda released an analytical piece on the “scenario for electing Kuchma for a third term, proposed to Medvedchuk by Russian political technologists.” Here are some highlights of what the Russians proposed to Medvedchuk and Kuchma:

“Today’s situation is such that for the population, all decisions are made personally by Kuchma. Others — prime minister, head of his administration, ministers, ‘governors’ — execute his will. Therefore, the president bears all the responsibility. Others are accountable as more or less successful implementers of his decisions. Hence, the main task of setting up this storyline is to portray Kuchma’s ‘departure’ in such a way that it is de jure a simulation, but de facto, it is believed.”

The Russian political technologists then proposed the following scenario: Kuchma seemingly goes underground and initiates a constitutional reform that ostensibly transfers his power to the government, parliamentary majority, and regional authorities. Then, an artificial division between the country’s east and west is intensified; Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych are to personify this conflict; local elites are provoked (by appointing individuals from the east to head western regions, which displeased voters as well as elites) — the country plunges into “controlled chaos”. And Kuchma, as if a savior, returns to lead the country, becoming a guarantor of stability and development, in contrast to politicians “who think about themselves, not about the people.”

Ukrainska Pravda authors concluded that “Ukraine was supposed to become a testing ground for implementing the ideas of Russian technologists. Particularly touching is the fact that, besides Kuchma, the second winner in this scenario was supposed to be... correct, Medvedchuk.”

Eventually, the idea of a third term for Kuchma was abandoned. Instead, another constitutional innovation was proposed. The political forces of President Leonid Kuchma and Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych suggested weakening presidential power and transferring to the Verkhovna Rada the right to choose the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. This would have strengthened the power of the future prime minister, whether Kuchma or another pro-government player and tied the hands of the future opposition president. In April 2004, an attempt was made to vote on the relevant constitutional amendments in parliament, but the Rada fell short by 6 votes. The forces of Viktor Yushchenko and Yuliya Tymoshenko, then in opposition, opposed such constitutional changes as they anticipated victory and a rise to power. However, during the height of the Orange Revolution, the old guard, represented by Kuchma and Yanukovych, identified the weakening of the presidential vertical and the corresponding constitutional changes as a key demand, in exchange for which President Kuchma agreed to organize a re-vote of the second round of the presidential elections. The opposition agreed to this ultimatum, and when Viktor Yanukovych became president in 2010, the 2004 political reform was canceled, and the 1996 Constitution with a presidential-parliamentary system of governance was reinstated.

2004: The “Unconstitutional” Victory of Viktor Yushchenko

The first and second rounds of the 2004 presidential election in Ukraine took place on October 31 and November 21, respectively. The election race was marked, among other things, by the poisoning of one of the candidates, Viktor Yushchenko, with dioxin on the eve of the voting. Furthermore, a dirty political tactic involving the artificial division of the country was employed perhaps for the first time — one candidate’s team, Viktor Yanukovych’s, accused Yushchenko and his team of allegedly dividing Ukrainians into three “kinds.” Following the falsified results of the second round, Viktor Yanukovych was declared the winner — Putin even managed to congratulate him on his victory. However, due to the falsifications, the second-round results were contested.

As a result, the country was engulfed by a wave of street protests supporting the opposition, demanding the annulment of the election results. These events became known as the Orange Revolution. The Supreme Court annulled the results of the second round in November and scheduled a “third round” of elections (a re-run of the second round), which took place on December 26, 2004. The repeat voting of the second round was conducted under the supervision of international observers, almost all of whom confirmed that the elections were held without massive violations and were very close to European democratic standards.

“I don’t know of any country with such a legal norm as a re-vote. It won’t solve anything. Re-voting can be done a third time, a fourth time, a twentieth time until one side gets the desired results,” Putin said during a meeting with Leonid Kuchma when he traveled to Moscow in December 2004, in the midst of Ukraine’s political crisis. Putin expressed Moscow’s desire to intervene in Ukraine’s internal affairs, a general disregard for its sovereignty and the Supreme Court’s decisions. “No matter what internal political storms rage, we hope all parties will remain within the framework of the law and the current Constitution. We are ready to participate in resolving the situation within the frameworks you consider possible for us,” he added. The Kremlin was then betting on Moscow-oriented Viktor Yanukovych, so it accepted his defeat with reluctance.

The events of 2004 would continue to haunt the Russian dictator even 20 years later. “They invented a third round of voting. What the hell is a third round? It’s not provided for by the Constitution. This is a coup d’état!” Putin said in 2023. He reiterated this point in 2024 in an interview with American journalist Tucker Carlson, “The USA supported the opposition and appointed a third round. This is a coup d’état.”

At the time, Ukraine was the only post-Soviet country with a pro-Western opposition movement whose coming to power would mean democratization, a departure from Moscow’s sphere of influence, and a course toward EU and NATO integration. As a result, Russian propaganda tried hard to discredit the choice of the majority of Ukrainians and present it as one that allegedly contradicted the Constitution.

2014: Turchynov and the “Coup d’État”

In February 2014, when the Euromaidan protests entered a more radical phase, Ukraine faced the reality of its president fleeing the country. On February 22, the Verkhovna Rada passed a resolution declaring Yanukovych’s withdrawal from fulfilling his constitutional duties and scheduled early presidential elections for May 25, 2014. This decision was supported by 328 MPs. The duties of head of state were assigned to then-Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada Oleksandr Turchynov. Turchynov also assumed the responsibilities of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. These events are consistently labeled by propaganda as a “coup d’état,” thus questioning the legitimacy of the post-Yanukovych government.

At that time, the Kremlin perceived Turchynov’s appointment and the application of Article 112 of the Constitution as a “coup d’état.” Currently, Putin refers to the same article to argue the “constitutionality” of Chairman Stefanchuk as the legitimate head of state. This once again demonstrates that propaganda uses references to the Ukrainian Constitution as it sees fit.

In 2016, a trial began in Moscow’s Dorogomilovsky Court based on a lawsuit filed by former MP from the Party of Regions, Volodymyr Oliynyk, seeking to recognize the events of early 2014 in Ukraine as a “coup d’état.” Any attempts through a Russian court to prove a “coup d’état” in Ukraine and the illegitimacy of the power change were legally void but demonstrative. The Kremlin has not abandoned the idea of reinstating the “legitimate” Yanukovych and branding the current Ukrainian authorities as unrecognized usurpers or a “junta.” We have detailed how Russian propaganda tries to scare its audience with the “bloody Kyiv junta” here.

The Russian propaganda machine vehemently promotes the message that Zelenskyy’s five-year term has ended and he has lost legitimacy as president. However, the “legitimacy” of Viktor Yanukovych, elected in 2010 and absent from the country for the past ten years, is not questioned. He emerges from political oblivion to present “peace plans” for Donbas, as a potential Gauleiter of Ukraine in case of its capture by Russian forces, or as a participant in Putin and Lukashenko’s negotiations on drills involving the use of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Federalization, Minsk Agreements, Medvedchuk’s Plan

One of the Trojan horses that the Kremlin attempted to slip to Kyiv was the abandonment of the unitary state structure in favor of implementing the idea of federalizing Ukraine. Just days before the start of Euromaidan, Putin spoke about federalization as the only possible path for Ukraine. After the annexation of Crimea and the onset of war, the topic of federalization began to be heavily promoted. Such a structure would have allowed Russia to more easily and legally “absorb” regions of Ukraine. Although federalization was not directly stipulated in the Minsk agreements, Moscow interpreted the idea of autonomy for the territories it had seized as necessitating Ukraine’s adoption of a federal structure instead of a unitary one. This would have meant Ukraine recognizing some status for the territories occupied by Russia, which were oriented towards Moscow rather than Kyiv.

“There is a clearly defined sequence and order for implementing these agreements, which clearly indicates political reform, special status, a plan for a truce, and other points,” said Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s press secretary, in 2015. Then-President Petro Poroshenko assured that Ukrainians were in favor of a unified and unitary country, rejecting any federalization.

In addition to “external” voices pressuring Ukraine to amend its Constitution, propaganda also utilized “internal Ukrainian” voices. Putin’s compadre Viktor Medvedchuk, now suspected of high treason in Ukraine, was one of the advocates for the country’s federalization and for amending the Constitution accordingly. For instance, in 2016, he stated, “The worldview of Galicians [referring to residents of the West of Ukraine] is so alien to the residents of the Donbas that attempts to impose a single template on all regions inevitably led to disintegration. Only a federal structure could save the country from it.” Thus, Medvedchuk sought to “stitch” Ukraine together by creating favorable conditions for further regionalization and polarization.

He repeatedly stated that “it is necessary to return the Donbas to Ukraine, and Ukraine to the Donbas.” However, this “return” in his vision was to consider the interests of Moscow, the separatists, and pro-Russian forces in Ukraine, but not of Kyiv. In early 2019, he unveiled his own “peace plan,” proposing to include an autonomous Donbas region in the Constitution of Ukraine. According to Medvedchuk, such amendments to the Ukrainian Constitution were based on the Minsk agreements and aligned with the Normandy format declarations.

“I am personally a supporter of a federal structure, always have been and will remain, because I believe that a federal structure is the only remedy against the disintegration of our country. But it’s not about that now, although this can only be achieved through constitutional changes, and this is not separatism. The Constitution of Ukraine provides for the autonomy of one of its regions — Crimea. And the status of autonomy is outlined in the Constitution of a unitary state. I am not proposing anything new,” he said.

“The red line (for Ukraine) is not to change the Constitution of Ukraine under any circumstances, no matter what Kremlin propagandists say about including the special status of the Donbas in the Constitution,” Oleksiy Reznikov, then Minister for Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine, voiced Kyiv’s stance on the matter. Medvedchuk’s plan, as well as the Minsk agreements, which were referenced by both him and the Russian side, were bait designed to trap Ukraine. De jure, federalization would have allowed for regional autonomy, but in reality, it would have meant Kyiv voluntarily relinquishing control over parts of its territory already under Moscow’s influence. Hence, the rhetoric from pro-Russian forces and the Russians themselves regarding the implementation of the Minsk agreements and constitutional changes was very forceful.

2024: A New Wave of Constitutional Revisionism

Following the full-scale invasion, the Minsk agreements lost their relevance, and revisiting the topic of constitutional revisionism seemed pointless. However, the Russians have started pushing the narrative of Zelenskyy’s “illegitimacy” and recognizing the Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada, Ruslan Stefanchuk, as the “legitimate” leader of Ukraine.

“But there is Article 111 of the Constitution of Ukraine, which states that in this case (failure to hold presidential elections), the powers of the supreme authority, effectively the presidential powers, are transferred to the chairman of parliament,” Putin said.

In reality, this article indicates otherwise, “The President of Ukraine can be removed from office by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine through impeachment in the event of committing state treason or another crime.” Article 112 of the Constitution of Ukraine states that “in the event of early termination of the powers of the President of Ukraine... the duties of the President of Ukraine until the election and assumption of office by a new President of Ukraine shall be performed by the Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.” Conditions for early termination would include physical inability to perform duties (due to health or death) or legal grounds (resignation or impeachment). Since none of these four conditions have arisen, there is no need or basis for transferring power to the Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada.

Verkhovna Rada Chairman Ruslan Stefanchuk directly responded to Putin’s manipulations of Ukrainian law: the Ukrainian Constitution and laws stipulate that Zelenskyy will remain in office until the end of martial law in Ukraine. He referred to part 1 of Article 108, which states, “The President of Ukraine exercises his powers until the newly elected President assumes office,” and advised “curious readers” of the Constitution of Ukraine not to read it “selectively.”

Accusations of “anticonstitutional nature” have been made regarding the events of 2004 — the victory of Viktor Yushchenko in the presidential elections — and 2014 — the appointment of Chairman Oleksandr Turchynov as Acting President of Ukraine in place of the fugitive Yanukovych. Additionally, propaganda has regularly voiced manipulations about the necessity of federalizing Ukraine and amending the Constitution in accordance with the “spirit” of the Minsk agreements. However, this apparent constitutionalism demonstrates an attempt to use the country’s supreme law to weaken the vertical power structure and destabilize the internal situation in Ukraine.

Moreover, Putin’s accusations of “illegitimacy” inadvertently highlight his own illegitimacy and constitutional violations. In 2021, a so-called nullification occurred, whereby Russia stopped counting the number of presidential terms a person had served and/or was serving when the amendments to the Russian Constitution took effect. Essentially, Putin enacted the scenario that Russian political technologists unsuccessfully attempted to implement in Ukrainian politics in 2003–2004.

One tactic of the Russian propaganda machine is to build castles in the air—an alternative reality with fabricated problems and their solutions. Playing with constitutionalism is one example of this propaganda technique. It is crucial that Putin’s disinformation campaign does not gain traction on the international level, making its neutralization one of Ukraine’s priorities today.

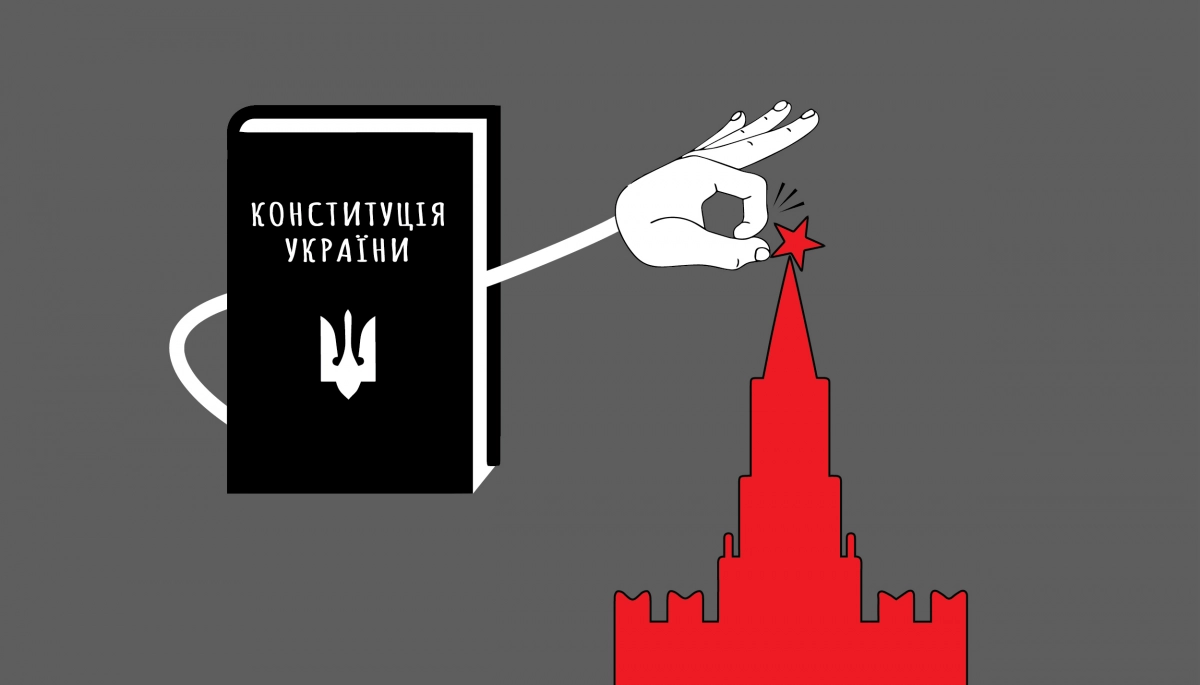

Illustration by Nataliya Lobach