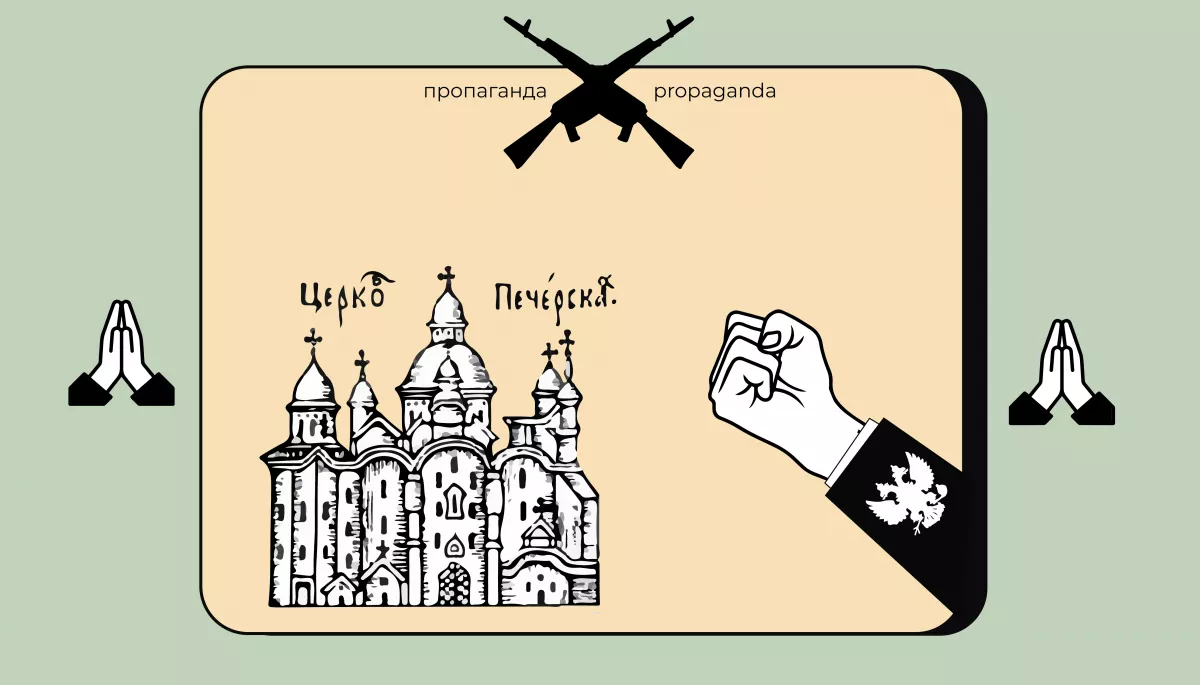

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine made an attempt in May this year to get a bill passed on its first reading, which aimed to outlaw the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP). While this attempt did not succeed, such actions underscore that the perception of this church in Ukraine has evolved from its past welcoming nature. Notably, the shift happened in 2018 when Ukraine was granted the Tomos of Autocephaly and further intensified amid the backdrop of the full-scale war. Prior to these events, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate had not experienced the alleged harassment that Russia is presently accusing Ukraine of. Over the past half-decade, Russia’s aggressive rhetoric about this supposed “harassment” has intermittently surfaced in the media landscape and became entrenched in November last year. This was triggered when the SBU initiated investigations into the dioceses of the UOC-MP and reported indications of pro-Russian activity among the bishops. Since these developments, criminal cases have been lodged against several clergy members, the UOC-MP has been ordered to vacate the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra (Kyiv Cave Monastery) premises, among other developments. However, the UOC-MP remains deeply rooted in Ukraine. Despite the war, Moscow’s priests continue to conduct services in thousands of Ukrainian churches, which are attended by their devout followers. This circumstance is largely attributed to Russia’s deployment of religious disinformation, a concept that we’ll explore below.

The protester outside the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra remarked, “Well, they are fools. Fools, do you understand?” after being doused with water by a UOC-MP priest. The church was due to vacate the monastery in March. While representatives of the Moscow Patriarchate haven’t left the monastery yet, they acknowledged that they are required to do so by July 4. Their failure to evacuate the monastery during spring sparked protests that can be more aptly described as disorder. As hundreds of Ukrainians held signs reading “Down with Moscow priests” and brandished yellow and blue flags, another large group, presumably also Ukrainians, conducted a prayer service and shouted at their opponents.

As an outsider, say, a Spaniard with a limited understanding of the situation’s context (a typical scenario for foreigners even when they recognize Russia as the aggressor), one might misconstrue this as a protracted conflict between individuals of differing faiths in Ukraine. In a worst-case scenario, they might even interpret this as a catalyst or justification for the war.

Protests at the Lavra persisted, with participants resorting to verbal abuse and water fights, while Russian propaganda concurrently spun narratives about intolerant Ukrainians denouncing their compatriots for selecting a different church. If a Spaniard or a Belgian were to encounter these Russian narratives (which were tracked on social media by Detector Media analysts, together with partners from 10 countries), they could be led to believe that this religious conflict is legitimate. While it is understood that propaganda is influential and Russia’s actions are deplorable, the reality remains that these protests are genuine, Ukrainians are indeed confrontational, and reconciliation seems improbable. These are the perceptions that propagate the idea that the situation is “not as straightforward as it seems”. Regrettably, this perspective isn’t confined to foreigners; it occasionally affects Ukrainians too.

However, discussions about these protests or the so-called “oppression of Orthodox practitioners in Ukraine”—a subject frequently broached in our domestic news outlets—often neglect to highlight Russia’s instigating role. This scenario is a clear example of shifting the blame for the disputes and clashes from the actual instigator to one of the parties to the conflict. Specifically, Russian propaganda has for years been pushing the notion of “the wrong Ukrainian church,” a fake Tomos, and branding Ukrainians as heretics and antichrists. What’s even more troubling is the success of these messages in influencing hundreds of thousands of individuals, both within Ukraine (including those still partially aligned with the UOC-MP) and beyond its borders.

Russian assertions about a single “true” church are intrinsically linked to a broader narrative about “one people,” “brotherly nations,” “a single culture,” and so on. In other words, for years, Russia has been promoting the notion that Ukrainians and Russians are essentially one and the same because they speak Russian (asserting, of course, that the Ukrainian language is just a dialect thereof), read Pushkin and Tolstoy (as if no books have been written in Ukrainian), listen to Tchaikovsky (ignoring composers like Lysenko), and worship one Orthodox God, who is supposedly only receptive to prayers led by Moscow priests. Any deviation from this, they argue, would incur divine wrath, prayers would be ineffective, and monuments to figures like Pushkin would start crumbling in cities far from Moscow, where “dialects” are spoken. It appears their predicted curse has come to fruition. But let’s refocus on the serious issue at hand — religious disinformation.

On the whole, the notion of religious disinformation becomes somewhat nebulous when applied to Russia’s warfare tactics against Ukraine, and consequently, in relation to its rhetoric about religious communities in Ukraine. Russia’s actions with respect to religious communities extend beyond the traditional understanding of religious disinformation. Moreover, when it comes to religious communities, Russia seems to focus on a rather restricted selection — two, or at most, three or four.

Generally speaking, in the language of nerds analysts, including myself, religious disinformation is characterized by the spread of skewed or deceptive information that instills negative perceptions, bolsters stereotypes of different faith groups, and ultimately, fuels discrimination against them. Propaganda paints religious communities as potentially harmful or extremist, using stereotypes and false information to induce fear in society. This theme is extensively discussed by American scholar David Elcott, who suggests that the weaponization of religion is used as a pretext to curb freedoms and marginalize minorities globally. He observes that post World War II, religious movements have increasingly identified with populist nationalism, which often presents itself as the defender of a nation’s “authentic” values, traditions, and interests, defending against threats from globalization, immigration, or international organizations. Elcott contends that religious identity is an even more powerful force for affirming national belonging than personal religious beliefs and practices. He points to the surge of anti-liberal political movements and leaders: the right-wing populist party Alternative for Germany, Marine Le Pen in France, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Narendra Modi in India. Political movements that were not originally founded to defend the interests of believers have now become fervent protectors of the concept of “preserving purity and authenticity”, which includes religious aspects, and resisting the “foreign” influences on their nation, religion, culture, and values.

Is Russia engaging in similar activities? The answer is both yes and no. Russia seems to target one religious community, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, indicating a desire to dismantle it, claiming that it’s allegedly inauthentic. On the other hand, Russia articulates a commitment to safeguard and nurture a religious community, the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, which has a longstanding presence in Ukraine.

While examining religious disinformation on social media, Detector Media’s researchers encountered a challenge: it was often difficult to differentiate genuinely pro-Russian messages targeting a religious group from similar Ukrainian messages. I’ve termed such phenomena as “indigenous xenophobia.” There’s a reality to Ukrainians displaying unfriendliness towards religious, ethnic, or gender groups. It’s regrettable but not unexpected, given that all people can be hostile to the unfamiliar. Yet, what sets their messages apart from pro-Russian ones? They’re predominantly just the individual viewpoints of a particular group of people — often a marginalized one. Conversely, Russia disseminates its messages in a coordinated fashion with clear objectives, both domestic and international. For instance, stirring up discord: Russia gains from Ukrainians fighting among themselves, crafting an image for foreign media that Ukrainians can’t reconcile with each other, thereby deflecting Russian involvement. Internal conflicts among followers of different faiths further divides society amid the already trying times of war. This internal strife distracts from the most important issue — the fight against Russia, which is destroying cities and villages and killing Ukrainians.

For its domestic audience, Russia portrays a negative image of the Ukrainian church and of Ukrainians as “intent on eliminating Russian priests.” Russian propaganda does this to demonize the opponent and to intensify Russians’ willingness to fight Ukrainians because they are perceived as “different and opposing the church.” Indeed, the propagandists conveniently omit that Ukraine’s attention to the churches of the Moscow Patriarchate is strictly due to national security concerns. It’s acceptable, given that the clergy of this denomination have been disseminating pro-Russian messages and even praising Russia for years. Examples include Onufriy, Metropolitan Paul the Mercedes, Dmitry Sidor... and Luka Zaporizkyi, who at the onset of the full-scale war against Ukraine, stated that Ukrainians deserved Russian bombings because “they tolerate gay parades in Kyiv, and therefore they are against God and deserve the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah.”

In contrast, to Western audiences, Ukrainians are painted with a broad brush of being intolerant xenophobes, rejecting anything beyond their own, and supposedly violent and threatening, due to supposed acts of burning churches and assaulting priests. Yet this characterization hardly seems to fit Ukrainians, does it? It’s reminiscent of someone else, isn’t it? I would argue it’s reflective of the Russians. It’s a classic case of mirroring, as Russians are the ones inclined to homogenize as much as possible: their culture, language, and history.

While promoting this homogeneity, Russia manipulates values, tossing them around with claims that everything in their realm is canonical and right, while everything on your end is wicked and insignificant. In reality, this rigid Russian viewpoint is discernible not only in the realm of religious disinformation. All Russian disinformation, however blatant it might sound, is imbued with this dogmatic approach. And it goes beyond just disinformation. In other words, “you’re either Russian or gay,” “you’re either for Putin or you despise Russia.” It’s akin to the old abusive adage, “you will be either mine or no one else’s”. Russia employs this strategy of value contrast when discussing Ukrainian refugees and women, and numerous other subjects. All these actions and rhetoric underscore one fact: Russia is an aggressor. While this could change, it’s unlikely in the foreseeable future. Abusers might require years of cognitive behavioral therapy, something Russia has not yet attempted. And the disinformation about religious communities that Russia disseminates is stale, it lacks any substantial flavor. This is unlikely to change either. Hence, it’s wiser to disregard it and instead delve into our comprehensive study.