Українською читайте тут.

At first glance, it seems like a musical concert, but upon closer inspection, it is a means of state propaganda.

Since New Year’s holds an almost sacred significance for Russians, and the nation’s entertainment industry functions as a propaganda tool of the Kremlin, New Year’s television specials and projects have become a part of Russia’s state information policy, albeit in a glossy package. Naturally, these shows feature an abundance of Russian military personnel whose detailed biographies are even read out on air.

We analyzed eleven New Year’s programs aired on Russian state or state-funded channels, as well as channels owned by enterprises affiliated with the aggressor state’s government. Below, we detail the specific messages promoted in these programs. The list of analyzed broadcasts includes:

- "New Year’s Night on Channel One: 30 Years Together!", Channel One, 2025

- "New Year’s Night on Channel One", Channel One, 2024

- "New Year’s Little Blue Light on Shabolovka", Russia-1, 2024 and 2025

- "New Year’s Apartment Show with Margulis", NTV, 2024 and 2025

- New Year’s Special of Comedy Club, TNT, 2025

- "Not the Diamond Arm", TNT, 2025

- "Good Songs", TVC, 2025

- "Favorite Songs on Zvezda", Zvezda, 2025

- "Not the Little Blue Light", Tsargrad, 2025

What New Year’s Specials Reveal About Russian Propaganda Trends

Russian television channels such as Russia-1, Channel One, TNT, TVC, Tsargrad, and NTV play a key role in disseminating propaganda and implementing Russia’s official policies, particularly during its war against Ukraine. This has led to Western countries imposing sanctions on these networks.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the European Union, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and other nations imposed restrictions on Russian media. Initial measures included blocking the broadcasting of Russian channels, such as Russia-1, Channel One, and NTV, across the EU. Restrictions extended to satellite transmissions, cable access, and online platforms like YouTube. Meta, the owner of Facebook and Instagram, limited the availability of these channels’ content on its platforms.

In addition to broadcasting bans, financial sanctions prohibited Western companies from collaborating with these Russian media. This included halting advertising, licensing technologies, and using content distribution systems. Personal sanctions were also imposed on hosts, journalists, and executives of these channels, such as Dmitry Kiselyov, Vladimir Solovyov, Olga Skabeyeva, Tigran Keosayan, Konstantin Ernst, and others who have become the “faces” of Russian propaganda. Since 2022, Ukraine has also introduced sanctions against numerous Russian propagandists and state-run channels.

New Year’s programs, commonly known as “New Year’s Little Lights” (ogonki), hold a special place in Russian television. These shows have become an integral part of Russian cultural tradition, though, in recent years, they have taken on a pronounced propagandistic tone. The “little lights” broadcast on these channels feature performances by popular artists who openly support Russia’s aggressive policies. Participants use these platforms to voice their endorsement of the regime’s actions, and the concert themes promote “patriotism” while glorifying the state.

While the content of the 2024 and 2025 New Year’s specials on the mentioned channels differs little, production trends highlight the state of the Russian media system, particularly its funding. For example, Russia-1 and its state-owned parent company, VGTRK, are among the few that could afford to produce the “lights” on nearly the same scale and in the same format. The Zvezda channel, managed by the Russian Ministry of Defense, offered similar content but as a standalone television product, unlike other channels that relied heavily on reruns of previous years’ programs.

TNT, for instance, managed to finance a remake of The Diamond Arm through its Comedy Club with jokes referencing “parallel imports.” Conversely, Channel One created a “lights” episode using clips from older New Year’s shows, possibly indicating financial difficulties. Other channels followed a similar path: NTV produced only a special edition of The Mask show and re-aired its previous year’s “lights” with a few new performances, while Tsargrad filmed a show without an audience.

These trends suggest that the state or affiliated entities have reduced funding for these channels, and sanctions have impacted advertising revenues. Therefore, future sanctions and restrictions on Russian media products could target these vulnerable areas to further undermine their operations.

Special Greetings

Propaganda has permeated every entertainment product on Russia’s state-run television channels, a fact evident from the very first moments of their programs. For instance, this year’s “New Year’s Little Blue Flame” on Russia-1 began with wishes for “peace” and affirmations that Russia is an “exceptionally great country.” Propagandists relentlessly emphasize Russia’s greatness, underscoring its record-breaking territorial expanse, which aligns with the state’s imperialist policies.

For example, before one of the performances, the hosts reminded viewers that Russia is a “vast and beloved homeland” where it snows in the north, but snow is unheard of in the south. This ties into the Russian propaganda narrative of the “Russian world” stretching “from Kamchatka to Warsaw,” a theme frequently perpetuated through various fakes and manipulations that Detector Media has previously exposed. Furthermore, this rhetoric borrows directly from Soviet-era propaganda, signaling Russia’s obsessive desire to return to the times of the USSR and forcibly drag its former subjects back into that era — continuing its aggression against Ukraine’s sovereignty.

Expressions of “patriotism” also featured prominently in the greetings from celebrities, which will be discussed in greater detail below. These messages revolved around boundless love for the motherland and aspirations for Russia’s success. On the New Year’s program of the Tsargrad channel, owned by Konstantin Malofeev, a Putin-aligned oligarch under sanctions, there were comments about the tradition of watching the president’s New Year’s address via projector and singing the national anthem as a family.

There were also subtle maneuvers to navigate restrictions: due to the official opposition to mentioning peace outright, participants had to specify that they were speaking of “peace in our home.” Particularly amusing was the remark made by comedian Yevgeny Petrosyan on Russia-1, who shared a nostalgic story about how a concert he attended at the age of seven as a “postwar boy” inspired his career. He added that the joy he saw in people during those challenging times motivated him to pursue a stage career, which turned out to be centered on jokes about mothers-in-law and drunk husbands that he considers comedy. This served as a veiled yet rather transparent suggestion that even in “difficult times” — an euphemism for war — people “need entertainment.”

On the other hand, there were more aggressive “greetings,” such as those aired on Tsargrad. These included wishes for “plenty of ammo,” for the enemy to experience bad weather so drones couldn’t fly, and for vehicles not to break down on their way to the frontline. Given Tsargrad’s self-branding as Russia’s “first conservative” channel, such messages are unsurprising, yet they highlight the diverse forms propaganda can take.

Musical Propaganda

The selection of musical performances in these programs was far from coincidental — the proportion of “patriotic” songs, folk compositions, and Soviet hits was notably high compared to the number of lyrical pieces about love. These musical choices often reinforced the propaganda messages disseminated during the New Year’s broadcast and throughout the year. For instance, the frequently repeated narrative about Russia’s vast territorial greatness was underscored by Lev Leshchenko’s performances of songs about the “beloved homeland” on Russia-1.

Unsurprisingly, the program also featured songs by Lyube, known as “Putin’s favorite band.” Another propagandist favorite, Shaman, performed two songs: one about the “unique qualities” of the Russian soul, a point later reiterated by the hosts, and another, a duet with Grigory Leps, about the ideal “real man.” The sexist undertones of Russian propaganda were further emphasized through performances and jokes that portrayed women primarily as cooks and “keepers of domestic comfort.” For instance, Yuri Antonov performed a song about teaching someone “how to be a good girl.”

The special programs also revealed that Russians still care about their global image. Some invited artists were introduced as having “worldwide fame,” and during an NTV concert, Olga Kormukhina performed songs by Led Zeppelin and Tina Turner.

The true star of the evening was Tatiana Kurtukova, who appeared on all major New Year’s broadcasts, sometimes multiple times in a single program. She is the performer of a propagandist hit that even reached foreign TikTok segments, celebrating “Holy Rus’,” which, for others, is a “thorn in the side.” On Russia-1, Kurtukova performed the same “hit” alongside “artists from Crimea, Kherson, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions” (whose names were not even mentioned). On TNT’s special edition of Comedy Club, she performed a parody version of the same song with club residents, including a line about “a certain red-haired president” singing along, alluding to Donald Trump.

Kurtukova’s song is a logical continuation of Oleg Gazmanov’s propagandist method, so it came as no surprise that the two musical propagandists performed together on Russia-1. Their duet featured a “new song” with lyrics about “the eyes of the homeland,” “grandfather’s medals,” and the end of World War II with a “peaceful May dawn,” exemplifying how Russian agitprop instrumentalizes and manipulates world history to advance its geopolitical agenda.

There were plenty of other notable moments. For example, Stas Mikhaylov performed “If You’re Waiting for Me” on Russia-1, a performance made more poignant by an audience filled with soldiers (a topic we address below). Dima Bilan’s performance with a young gymnast, who had won a children’s competition, also hinted at peace, beginning with the release of white doves.

Also featured was Elena Sever, the wife of Vladimir Kiselyov, head of RMG — one of Russia’s largest media holdings specializing in radio broadcasting, music events, and Russian pop culture promotion. The holding cooperates with the Russian government, advancing cultural policies aligned with the official Kremlin. Since its restructuring in 2015, RMG has come under state control. This process was accompanied by a change of leadership and a pivot toward supporting the official ideology. Kiselyov and his holding work closely with government agencies on cultural initiatives and are used as a tool to promote patriotic sentiment in popular culture.

Appearing on air was Emin Agalarov, the son-in-law of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and owner of the Crocus City Hall, the site of a terrorist attack in early 2024, when Russian propagandists had attempted to blame the incident on Ukrainians. Agalarov performed a song by Muslim Magomayev on Russian state television — an embodiment of the English phrase “subtle foreshadowing”. The concert was recorded in November but aired after the crash of an Azerbaijan Airlines plane in Russia, caused by Russian air defense systems. Agalarov’s father-in-law is now demanding an apology from Russia for the incident.

Russian television didn’t miss the opportunity to feature Ukrainian-born artists Ani Lorak and Oleksandr Panayotov. Additionally, Taisia Povaliy, alongside the Kuban Cossack Choir, performed the Ukrainian folk song “Ty zh mene pidmanula” (”You Deceived Me”). This performance exemplifies Russia’s ongoing efforts to appropriate Ukrainian culture.

Since 2023, numerous examples have emerged of Russian singers performing Ukrainian songs, either in their original versions or as adaptations. Russia’s cultural appropriation extends beyond Ukraine; in the “New Year’s Little Blue Flame” program on Russia-1, the Belarusian band Syabry performed a song in Belarusian about “loyal friends.”

Particular attention was given to the song “Moscow of Golden Domes” performed by Alexey Vorobyov on Russia-1. Interestingly, Vorobyov, who divides his time between Russia and Los Angeles in an attempt to conquer Hollywood, shared on social media about evacuating from wildfires near his home in California. Despite this, after singing about the niceties of Moscow on Russian television, he returned to his Los Angeles residence.

The song was even the subject of a discussion on “Good Songs”, a New Year’s program on TVC. Why is this significant? Because the song has direct ties to Ukraine. It is, in fact, a Yiddish folk song about a beautiful girl, arranged by composer Sholom Secunda from Oleksandriya in the Kirovohrad region. Secunda originally adapted a folk song for his play, after which an unknown author added Russian lyrics.

However, the hosts of the TV program claimed there was no evidence linking Secunda to the creation of this “truly Russian folk song” and insisted that despite the composer’s origins, the song supposedly “reveals the Russian soul.” This is yet another example of Russia appropriating the heritage of other cultures.

The “Cultural Front” of New Year’s Specials

Both this year and last, the overarching theme of Russia’s major New Year’s “lights” programs has been the country’s aggression against Ukraine, thinly veiled under the term “SMO” (Special Military Operation), particularly on Russia-1 and Tsargrad. While the subject was referenced only subtly in greetings and song lyrics, the presence and statements of “military correspondents,” “journalists,” and high-ranking Russian officials underscored that Russia’s information space is fundamentally military propaganda, with its media serving as a tool in hybrid warfare.

Familiar propagandists such as Dmitry Kiselyov, Ernest Matskyavichyus, Evgeniy Poddubny, Vladimir Solovyov, Olga Skabeyeva, and Vladimir Popov appeared on air, pledging to “continue delivering honest information about world events without embellishment” to the audience of Russia-1. Meanwhile, Tsargrad channel owner Konstantin Malofeev made an appearance during his channel’s New Year broadcast, calling 2025 “a year of hope” and sharing his thoughts on U.S. politics:

“The main person in the headquarters of our enemy has changed. He will, of course, begin his duties in 20 days, on January 20, but in any case, he is not the old maniac who went crazy, like Biden was, who simply hated us. He wanted to destroy Russia and personally hated Putin... And Trump is a pragmatic person in this sense, and so there is hope. I don’t want to say that it will necessarily come true, but at least there is hope, because there was none with Biden. Therefore, this is a year of tentative hopes on the most important issue — the war.”

He also stated that Russia has “sacrificed too many lives on the altar of victory to stop now” and claimed that “the negotiations that will definitely start with the Americans will be negotiations on the surrender of Ukraine, not on where we will stop.” According to him, Russia has no reason to stop because they have their Oreshnik [a recently much-bragged-about missile].

Tsargrad’s broadcast featured numerous high-ranking officials, such as Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova, who spoke about Russia’s “uniqueness” and how many foreigners supposedly admire it, claiming that Russia is “strong” because of this. Actor and State Duma deputy Dmitriy Pevtsov declared that Russia is “cleansing itself of the chaff” that had accumulated “in people’s minds” and “in the nation’s soul” over the past 30 years. These statements are more than just examples of typical propaganda narratives. They are also examples of conspiracy theories, including those framing Russia’s aggression against Ukraine as an effort to “end external control over Russia” and assert its “exceptionalism and superiority over other countries.”

Tsargrad’s New Year program also included creative expressions of the war theme. One participant brought a Russian military ration pack, unpacking it live for the hosts and praising its “bacon,” abundance of “pâtés,” “meat,” candies, and cookies. Another commentator described how Russian soldiers on the frontlines decorate Christmas trees with “deactivated grenades” and machine-gun belts.

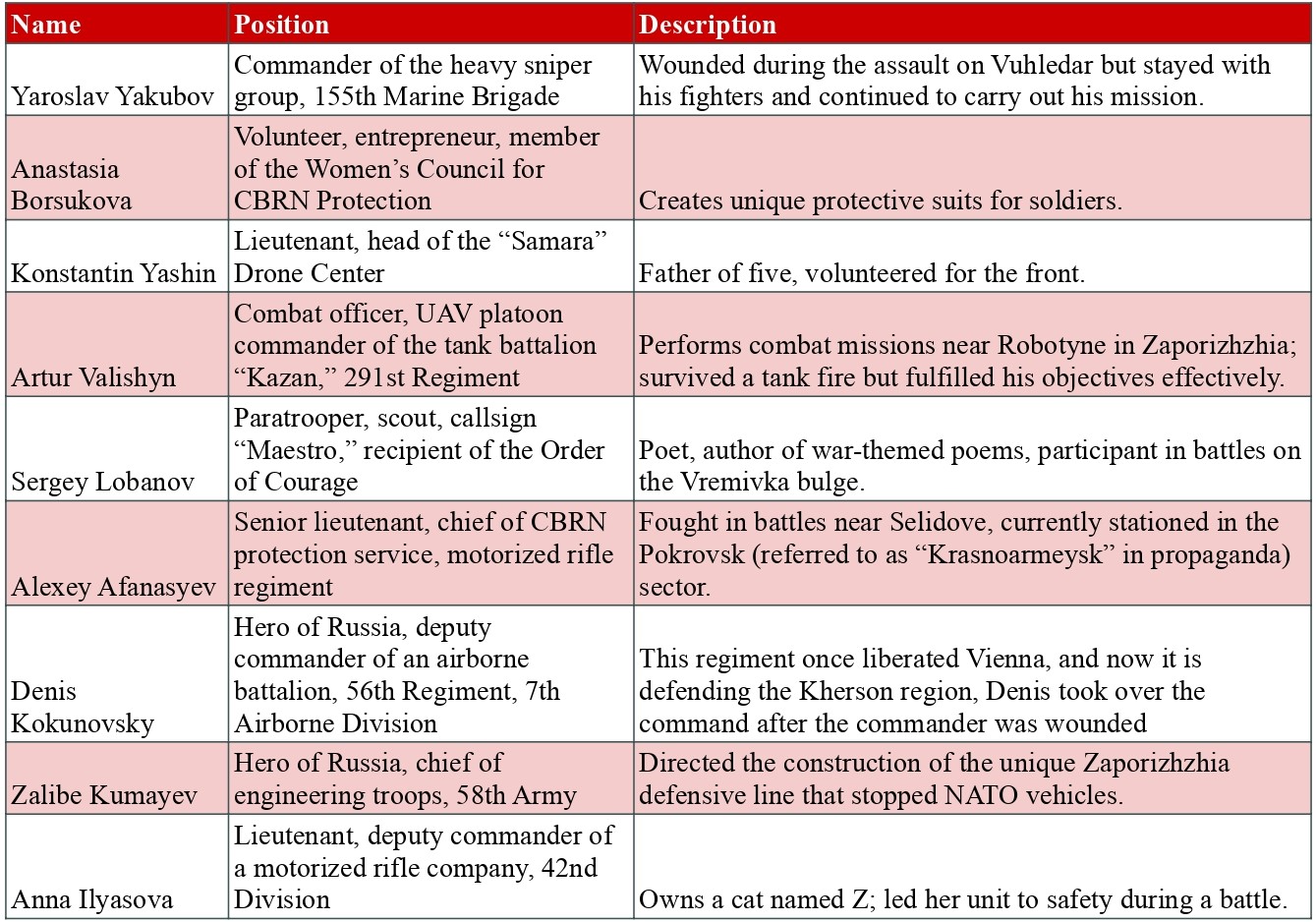

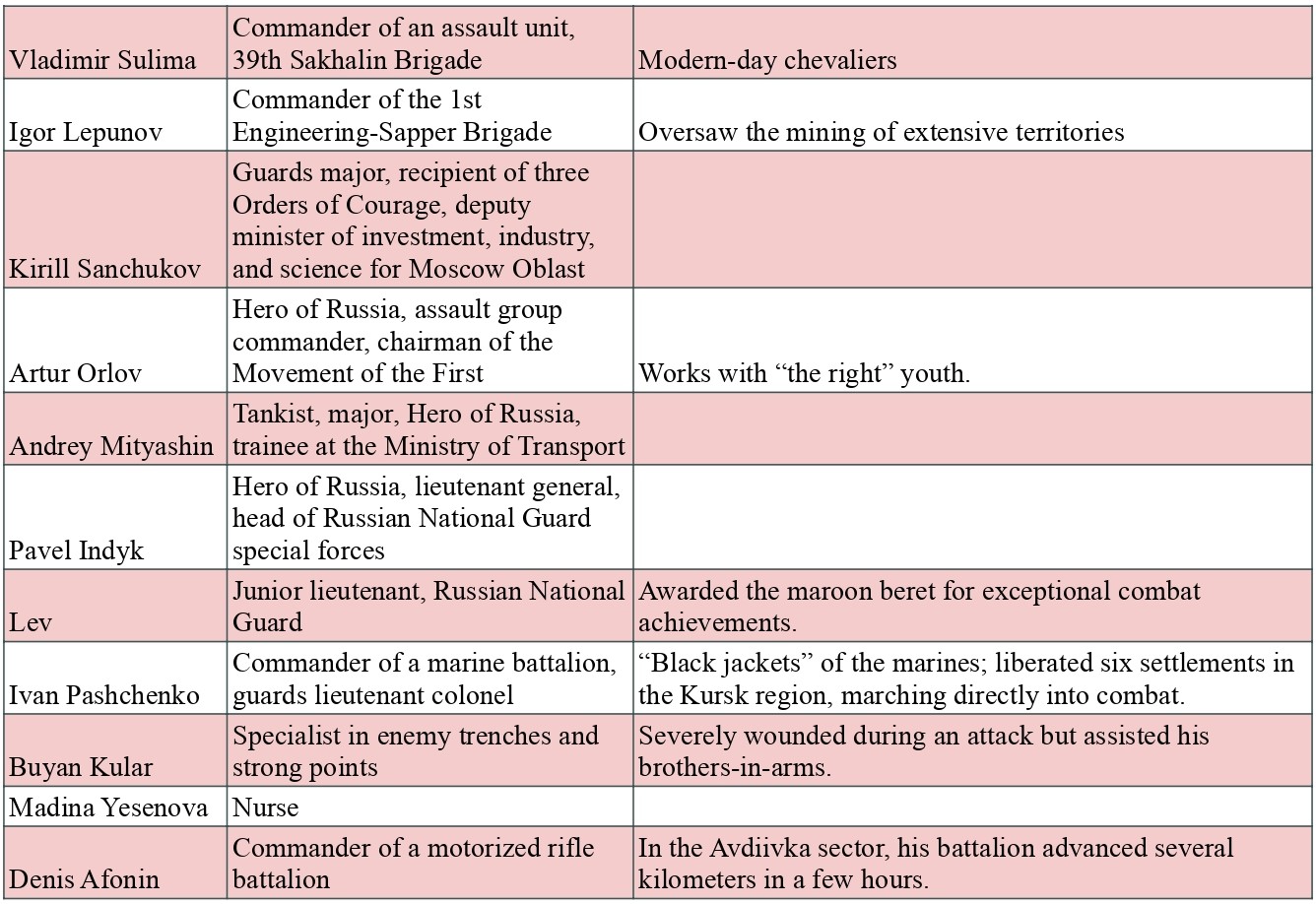

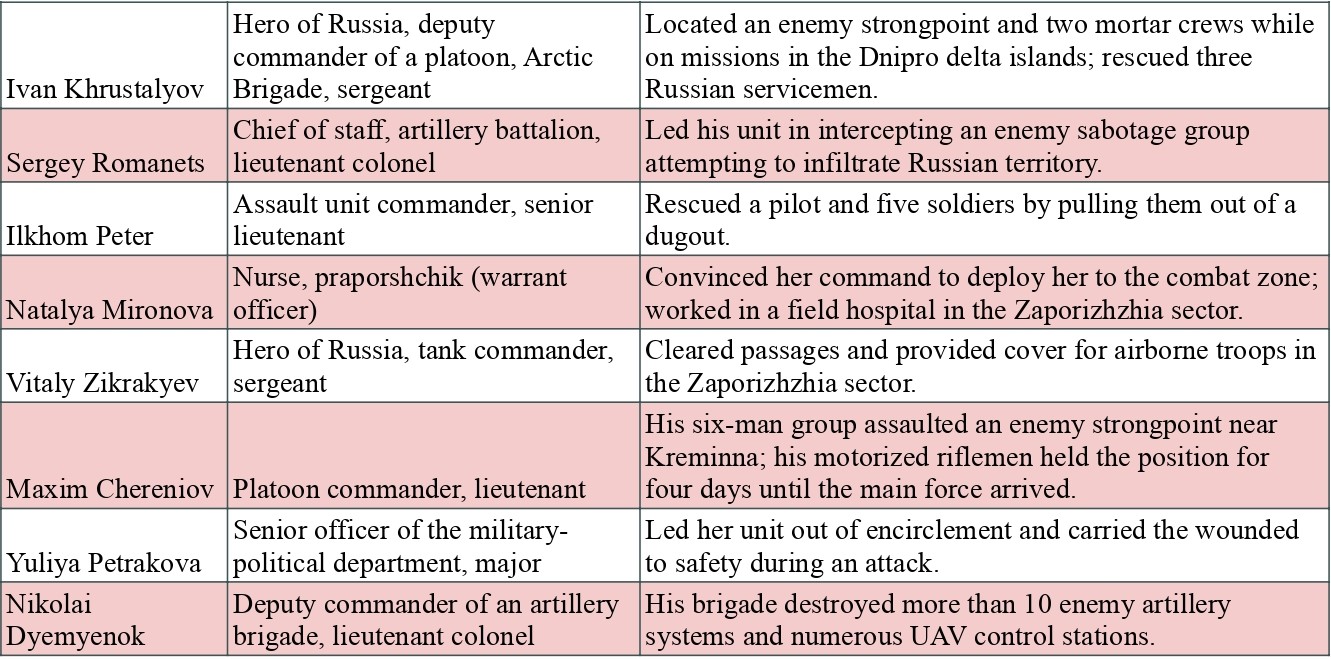

The hallmark of all these broadcasts was the direct presence of soldiers fighting for Russia against Ukraine. Unlike other Russian channels, Russia-1 openly named these soldiers, providing full names, ranks, and descriptions of their combat journeys (although some individuals were highlighted less prominently). These individuals were featured in thematic segments of the “lights,” offering wishes related to the war — calling for the “inevitable fulfillment of all SMO objectives” and celebrating the “grand purpose” of their actions.

While the complete or partial authenticity of all these dossiers remains uncertain, this approach illustrates a calculated balance between ignoring the war and actively propagandizing it. Over the two years, the total number of soldiers featured in these broadcasts likely exceeds the 28 given airtime this year, as detailed stories about their roles in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine were shared.

Profiles of Russian Military Personnel Featured in Special Segments of the “New Year’s Little Blue Light” 2025 Broadcast on Russia-1

Note: The information provided may be incomplete or fabricated for propaganda purposes. Descriptions and ranks are recorded as they were presented in the broadcast.

Propagandists gave special attention to the project “Time of Heroes”, the concept of which involves former participants in the so-called “special military operation” undergoing internships in Russian state and municipal government bodies. Vladimir Solovyov described this initiative during the Russia-1 New Year’s special, quoting Putin’s statement that “the elite of the nation are its workers and heroes.” In this way, Russia demonstrates how it is building a new cadre of individuals — drawn from combat veterans — to implement state policy objectives, further aligning its bureaucratic apparatus with imperialist tendencies.

Russian New Year’s “lights” are not merely entertainment products but also tools of propaganda used to shape public opinion both within the country and beyond. These programs subtly or overtly cultivate the image of a “stable and strong” Russia. They manipulate viewers’ emotions, creating an atmosphere of nostalgia and unity to distract from Russia’s crimes. These shows broadcast anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian narratives, mocking the West by portraying it as immoral or weak and attempting to justify Russian aggression. Additionally, these programs aim to reinforce the sense of a “unique Russian culture” that stands in opposition to Western values. They exploit patriotic themes, historical imagery, and calls for solidarity in the face of “external threats.”

Main page illustration by Nataliya Lobach