Українською читайте тут.

Historically, the Russian invasion of Ukraine isn’t the first instance of painting those living under occupation in a distinct light. During the Soviet era, inhabitants of regions occupied by the Germans between 1941-1944 were viewed with suspicion. If someone disclosed that they or their relatives resided in these occupied territories on application forms for universities, political parties, or jobs, it often resulted in denial. They faced scrutiny, questioned on why they hadn’t evacuated, joined partisan groups, made sacrifices, or even died for the “Soviet fatherland.” Countless civilians were branded as “untrustworthy” due to suspected collaboration. This led to the deportation of hundreds of thousands, including Crimean Tatars, other ethnic groups from Crimea, and Ukrainian Germans. Our research delves deeper into the contemporary xenophobia against inhabitants of temporarily occupied and de-occupied Ukrainian territories and the potential risks it presents.

Between 2014 and 2022, there was a societal debate regarding the procedures for reclaiming Ukrainian territories. Questions emerged about verifying individuals’ collaboration with occupying forces, deciding who was a traitor and who was not, establishing punishments for collaborators, and the extent of justifiable retribution. Following counterattacks by which the Ukrainian Defense Forces regained half of the territory lost to Moscow’s full-scale invasion, conversations shifted to the denizens of these reclaimed regions. They, too, became subjects of propaganda. As per the Kharkiv Institute for Social Research, one-third of Ukrainians empathize with those from the Temporarily Occupied Territories (TOT) who acquired Russian passports out of survival necessity. However, 14% believe that acquiring such a passport is a punishable offense. This polarization underscores societal confusion, making Ukrainians prone to negative propaganda and more susceptible to xenophobic attitudes promoted by propagandists. Many claims state that TOT residents lean more towards Moscow than Kyiv, resist Euro-Atlantic alignment, easily accept Russian citizenship, neglect supporting the counteroffensive, etc. Conversely, TOT inhabitants are uncertain about their future once the Ukrainian government regains control, leaving them susceptible to Russian propaganda, which convinces them that Ukraine holds no place for them and only mass trials and reprisals will follow after de-occupation.

An August 2022 survey by the Rating Group revealed that while 22% viewed the inhabitants of occupied Crimea positively, 23% felt the opposite. Moreover, a mere 14% had a positive perspective on residents of the occupied parts of the Donbas, with 47% viewing them negatively. This data highlights the deteriorating perceptions towards individuals from the TOT.

Even before the full-scale war, Ukraine had already started drafting plans for the seamless reintegration of previously occupied territories and establishing accountability for collaborators. In 2021, multiple bills aimed at criminalizing collaboration were proposed to the Verkhovna Rada. The Act “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts (regarding the Criminalization of Collaboration Activities)” was enacted in March 2022. However, Ukrainian society and its legal framework still grapple with unanswered questions. Although Ukraine doesn’t see citizenship acquired under duress during the occupation as a basis for losing Ukrainian nationality, there are still voices pushing to criminalize the acquisition of Russian passports. This legal ambiguity further complicates the situation for residents of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, and Crimea.

In this study, we focus on the analysis of xenophobia toward the inhabitants of the TOT and de-occupied territories and the influence of the Russian propaganda machine on social media.

Methodology Overview

Detector Media meticulously evaluated 56,997 posts from the Ukrainian segment of Facebook, YouTube, Telegram, and Twitter using data from Semantrum. The period under review spanned from September 1 to May 31, 2023. For a detailed breakdown of our data collection and processing methodology, see our dedicated section [link].

This study aims to shed light on the distinct xenophobic narratives targeting the residents of Ukraine’s temporarily occupied and reclaimed territories. We define the “Ukrainian segment” as posts originating from profiles, pages, groups, and channels either situated in Ukraine, marked as based in Ukraine, or identified by data providers as distinctly Ukrainian. Users or communities spreading Russian-centric content, either overtly or covertly, are tagged as “pro-Russian.”

On platforms like Facebook, where Russia has imposed bans, pro-Russian users are scarce. In contrast, this platform brims with radical pro-Ukrainian users championing stringent measures against what they view as the “disloyal populace” from the temporarily occupied and liberated territories.

Telegram, on the other hand, houses a dense population of pro-Russian users, largely due to its lax moderation. Even though both pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian factions are active here, their interactions are minimal. The ease of Russian language familiarity among Ukrainians could explain why they tend to peruse pro-Russian channels more than the other way around.

Meanwhile, YouTube is primarily populated by pro-Ukrainian influencers and national media.

Twitter’s usage leans more towards official communique and brief personal commentaries on news items.

Key Findings

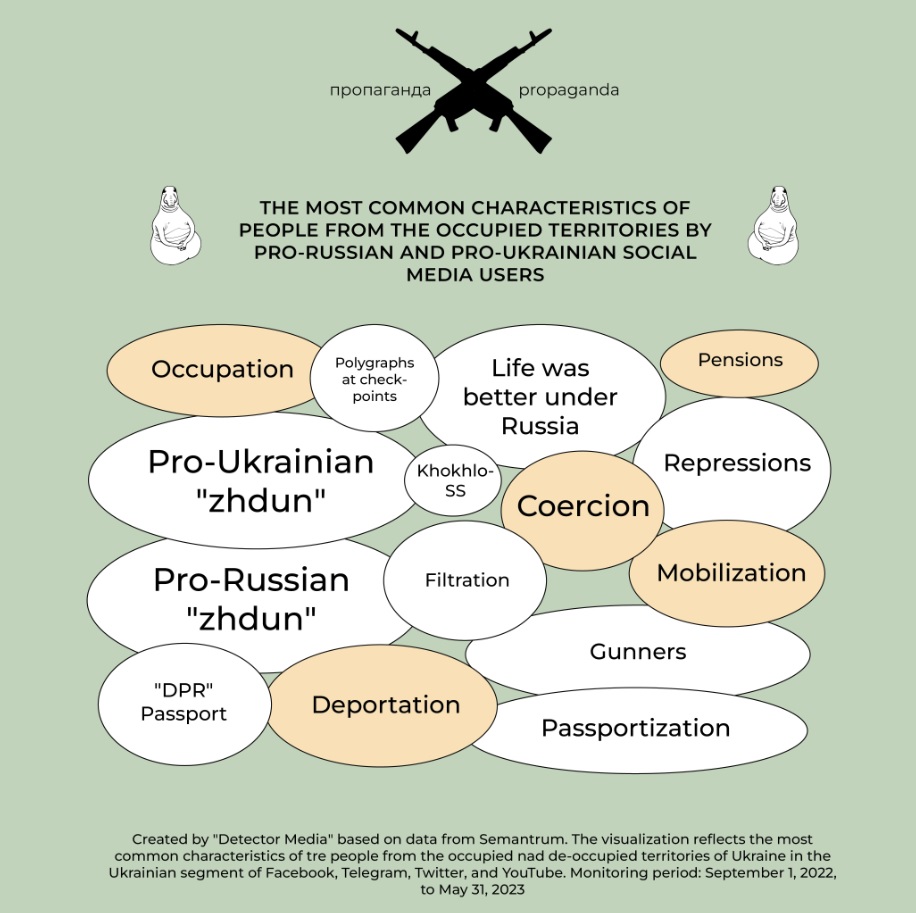

Zhdun as a Synonym for a Traitor on Both Sides of the Frontline

Drawing inspiration from Homunculus Loxodontus (also nicknamed “The One Who Waits”) sculpture by Dutch artist Margriet van Breevoort – a peculiar entity seemingly in perpetual wait – the term Zhdun in the Ukrainian socio-political context signifies individuals who remain in a territory governed by one faction but hope for the takeover by another. For the Ukrainian digital sphere, a Zhdun eagerly awaits the Russian army’s arrival, while the pro-Russian narrative views Zhduns as those yearning for de-occupation.

Zhdun according to Russian propaganda

Through the lens of Russian propaganda, these Zhduns are demonized as terrorists, plunderers, and murderers. The predominant advice from pro-Russian digital circles for Zhduns is deportation. They say that if you like living in a country that “doesn’t care about you, doesn’t wait for your return, and has been killing you for nine years,” Russia will give you a chance to go to Ukraine. Paradoxically, propagandists promote the idea that it is much more prudent to support Russia than Ukraine, because Russia is supposedly winning and prospering, while Ukraine is doing the opposite.

Pro-Russian users often call for lynching of “Ukrainian Zhduns” who are waiting for the arrival of the Ukrainian army in the territories temporarily occupied by Russia. “We have the impression that the “Ukrainians” are desperate for ordinary people to burn them in the central squares,” Telegram anonyms commented on the guerrilla activities of Ukrainians in the occupied territories. In this context, the authors of the posts refer to those who do not resist the occupation as “ordinary”.

“A lot of people are waiting in Donetsk...” pro-Russian Telegram users complained.

Residents of the temporarily occupied territories who support Ukraine and aid its Defense Forces are labeled as “mercenaries” by propagandists. Propaganda reports speak of Russian authorities “unmasking” these individuals. Pro-Russian online commentators suggest that while they have “sent the Zhduns to Ukraine but Ukraine refused to accept them.” Through such assertions, they aim to diminish the guerrilla actions of those in the temporarily occupied territories (TOT) and propagate the idea that Ukraine is indifferent towards these guerrillas. The underlying message is that Ukraine doesn’t genuinely value the people in these temporary occupations, implying, “Don’t bother trying to gain its approval.” This narrative culminates in the assertion that aligning with the Russian military is the only logical step: “You [Ukrainians under temporary occupation] now reside within Russia’s domain and should abide by our rules. Make the best of your situation.”

The primary goal of these narratives is to instill fear. Through agitprop, the intent is to leverage this fear, minimizing resistance against the Russian military. The message is clear: any opposition will be met with dire consequences, ranging from being exiled to an “unreliable Ukraine” to facing fatal repercussions. Recognizing that those Ukrainians in the occupied regions are hopeful for the Ukrainian Defense Forces, the Russian strategy hinges on sustaining an atmosphere of dread to retain dominance over these regions. Moreover, the propaganda seeks to paint Ukraine as being disinterested in its citizens currently under occupation. The underlying suggestion is that collaborating with Ukraine will only bring hardship and strain relationships with the occupation authorities.

Russian Propaganda Concerning Zhduns in Liberated Territories

Pro-Russian narratives regarding the liberated territories predominantly suggest “life was better under Russian rule.” Key messages disseminated by these propagandists encompass claims like: “Ukraine is neglecting the revitalization of liberated territories,” “While Ukraine is recruiting troops, Russia had granted a five-year conscription moratorium in the occupied areas,” and “pro-Russian citizens face rigorous scrutiny and repression in de-occupied areas.”

A distinct discourse surrounding the Zhduns within the Russian social media sphere became prominent during and post the Russian military’s expulsion from Kherson. Prior to the army’s withdrawal, some pro-Russian voices called for the aggressive “relocation” of the local pro-Russian populace, stating: “Forcefully move individuals to the left bank. It might seem harsh, but they’ll eventually appreciate it. The Kherson local government should initiate this forceful migration from the right bank. Allow those who choose to wait to do so, but give others a 30-minute notice to depart to the left bank.” Contrasting voices declared that “those who intended to leave have already done so” while simultaneously accusing pro-Ukrainian residents of “looting and waiting in their apartments.”

Upon Kherson’s liberation, Russian propaganda pivoted to asserting that life for pro-Ukrainian citizens become more difficult after the city was liberated. Numerous accounts alleged a significant decline in utility services post-occupation, suggesting that, unlike the Russians, Ukrainian officials were indifferent to the well-being of locals: “There’s no initiative to restore power, water, or gas.” These propagandists conveniently omit to mention the parties responsible for the destruction of civilian infrastructure during their retreat and subsequent bombardments.

A pivotal component of this propaganda emphasizes military mobilization in liberated territories. One propagandist sneered, “In Kherson, the Zhduns are now being drafted! The elation of seeing the yellow and blue flags was fleeting. Rumor has it that many evaded recruitment during the Russian occupation of Kherson. Now, there’s no turning back; you’re headed to the front lines!” Concurrently, they stress that Russian occupation administrations refrained from recruitment, promising locals a 5-year draft hiatus. Such declarations starkly contrast the reality, especially given the forced mobilization in temporarily occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions even before the full-scale invasion. This recruitment was so extensive that, according to former local militant leader Pavel Gubarev, Donetsk is nearly devoid of young men.

Russian propagandists claim that Zhduns face intense persecution in liberated territories. Both pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian Zhduns are allegedly targeted based on personal grievances. “In Kherson, Ukrainian Einsatzgruppen conduct ‘filtration’ to identify unwanted neighbors through denunciations. Because of such methods, innocent people who have been slandered for some material gain often suffer.” On the other hand, some propagandists claim that pro-Ukrainian Zhduns actively partake in this process, accusing their neighbors and handing over lists of “untrustworthy” individuals to the local police and the SBU (Security Service of Ukraine). This purported campaign is intensified by the use of polygraphs, a tool Ukrainian law enforcement is allegedly using to distinguish between pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian Zhduns: “Polygraphs are in operation, while checkpoints (16 in total) on this side of the Dnipro continue to verify citizen documents against the SBU lists.”

A primary tactic employed by these propagandists is highlighting instances of pro-Ukrainian “prisoners” who eagerly anticipated liberation but later allegedly felt “disappointed.” They claim, “Residents who remained in Kherson now wish for Russia’s return. And this sentiment isn’t exclusive to those who initially held our views. Even the ‘Ukrainian loyalists’ have had a practical comparison between life under Russian rule and the current situation.” The narrative stresses that it’s predominantly the pro-Ukrainian Zhduns who bear the brunt of the so-called “horrors” of liberation. As per Russian propaganda, they are the ones allegedly conscripted, arrested based on denunciations, or left without essential supplies like food, water, and electricity: “Bread has become a luxury. Many resort to drawing water from the Dnipro and then extensively boiling it, as not everyone has the patience to queue for potable water. As it stands, the first group of ‘Zhduns’ is set to be dispatched to the frontline come Monday.”

The Perception of Zhduns in Ukrainian Social Media Discourse

In the Ukrainian media landscape, Zhduns also surface — these are individuals who seem open to accepting either Russian or Ukrainian rule. Within the Ukrainian-focused segment of social media, contributors often discuss these individuals as a potential threat to Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Still, the predominant belief is that they can be “re-educated.”

Many in the Ukrainian social media segment depict “Russian Zhduns in Ukraine” as deceptive, “vatniks,” and even willing to betray Ukraine for a token amount. Notably, the Ukrainian side of social media doesn’t resonate with the same aggressive sentiments as seen in pro-Russian segments; there’s a noticeable absence of death threats. Instead, the emphasis is on identifying and engaging with Russia’s supporters. There’s a prevailing sentiment that the situation with Zhduns cannot be left unaddressed.

Geographically speaking, the Zhdun label was primarily attributed to residents of the frontline areas in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. The reasoning is their close proximity to Russia, increasing the likelihood of expecting the so-called “liberating army.” There are sporadic mentions of “Zakarpattia Zhduns” who purportedly desire to join Hungary: “Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the terrorist state’s interest in the Zakarpattia region has increased many times over. We need to be careful of supporters of Russia, which is also friends with Hungary.” This message was not too frequent, with only a few mentions of “Zakarpattia Zhduns” in our sample. Moreover, such messages were of a warning nature.

A contentious topic among pro-Ukrainian users is the perceived lack of consequences for individuals who collaborated with occupying forces or betrayed their neighbors. According to some, these individuals unabashedly accept humanitarian aid “from the same Europeans and Americans they disdain” and, in some cases, maintain their roles within governmental and educational institutions: “My daughter-in-law..., who dreamed of becoming a school principal (Oskil community) and was happy to burn Ukrainian books, demands to be entrusted with further work with students as if nothing had happened, and for some reason even goes to work!”

One video that gained attention featured a local from Vuhledar, who was evacuated despite not requesting to be moved. The frustration was palpable among pro-Ukrainian users, who felt that volunteers [that assist with the evacuation of civilians from frontline settlements] were risking their lives for pro-Russian Zhduns: “They brought a ready-made 10-ruble artillery observer into a peaceful city. After these words, they had to throw him out of the car.” Some expressed apprehension about regions occupied since 2014, fearing a significant pro-Russian sentiment: “And what else awaits us when all the territories are de-occupied because 80% of [the population] are against Ukraine? I have no idea what to do with them except to send them to Russia.”

Despite these concerns, the overarching sentiment in the Ukrainian segment of social media remains empathetic towards those under occupation, with many messages conveying support for TOT residents. Volunteer Kateryna Arisoy from Bakhmut aptly captures this sentiment: “TWhen they say that only those who were waiting for Russia remain there, only the Zhduns, it is a stereotype. When we see these people, we realize that they want to live in Ukraine. They were not waiting for anyone there.”

Russia’s Strategy of Illegal Passportization in Occupied Territories

Russia’s use of passportization has emerged as a pivotal tactic in its arsenal of soft power and hybrid warfare within the post-Soviet space. This strategy involves disseminating Russian passports, thus achieving multiple objectives. Firstly, it broadens Russia’s political, cultural, and ideological footprint on neighboring countries and regions it has long perceived as its dominion. Secondly, it enables Moscow to exert pressure on neighboring nations’ governments. For instance, before the 2008 war, the Kremlin utilized passportization as a means to deter Georgia from deviating from Moscow’s preferred geopolitical trajectory. Lastly, by establishing a significant number of its “citizens” in foreign territories, Russia can justify military interventions under the guise of “protecting its citizens.” This strategy has been in play since the 1990s in occupied areas of Georgia and Moldova. Post-2014, following the annexation of Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, this tactic was methodically employed in Ukraine.

In Crimea, the distribution of Russian passports became a commonplace occurrence. However, in the occupied areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, the passportization process remained limited until the beginning of 2023. Primarily, passports were granted to notable collaborators, representatives of fictitious “authorities,” and fighters of the 1st and 2nd Army Corps of the Russian army, which propagandists called the “armies” of the terrorist groups [LPR and DPR]. Alongside Russian identifications, fabricated passports of “DPR” and “LPR”, both Russian constructs, were also disseminated. These makeshift passports aimed to cloak the occupation under the guise of these “republics.” Any legal discrepancies arising from Russia’s non-recognition of these entities were anticipated to be rectified by the illegitimate “pseudo-referendums” in September 2022. Subsequent to these, Russia claimed a number of Ukrainian regions as its own. Occupation leaders were subsequently accorded Russian passports.

As 2023 commenced, there was a marked acceleration in the distribution of Russian passports within the temporarily occupied territories. This surge is attributable to Russia’s intention to conduct “elections” in these territories, slated for September 10, 2023. Another motive is to consolidate control over local inhabitants, with the Russian passport serving as a ticket to social welfare benefits. Russian propagandists project the possession of their passports by the temporarily occupied territories’ inhabitants as a sign that these individuals are now considered criminals in Ukraine. The implication is that they should align with Russia and avoid helping the Ukrainian Defense Forces and pro-Ukrainian partisans.

On social media, the promotion of passportization is predominantly conducted through accounts of collaborators and the pages of illegal occupying “administrations.” The local populace is persuaded to obtain Russian passports via local agitation, as well as a blend of intimidation and enticements – ranging from threats of losing essential services like healthcare and education to lures of social benefits or home restorations.

“The Increasing Russian Count”: Passportization Through the Lens of Pro-Russian Social Media

Contrary to expectations, pro-Russian social media narratives about the advantages of holding a Russian passport aren’t always in unison with the official Russian stance. Among these posts, the most commendable aspect mentioned is the efficiency of the passport distribution process. Regular updates on the volume of passports disseminated are also a recurring theme. A typical sentiment expressed is the ease of obtaining this passport amidst daily routines: one notable propaganda message highlighted, “Donetsk miners are uniquely positioned. They can apply for a Russian passport right within their workplace. Migration services have arranged for direct, on-site applications across all DPR mines.”

Pro-Russian social media users and propagandists running Telegram channels targeting residents of the temporarily occupied territories considered both the refusal of Ukrainians to accept Russian passports and their receipt to be threats to Russia. Those who decline the offer are often depicted as enemies, with threats of dire consequences: “Those who decline the Russian passport come under the radar of special services, leading to deportation.” Paradoxically, even those Ukrainians who embrace the Russian passport aren’t wholly trusted by these propagandists, continuing to be perceived as “ideological Ukrainians.” Proposals to strip such “recently Russianized” individuals of their new passports for undermining SMO [special military operation] or other reasons were seen. The underlying motive seems clear: to keep an ever-present shadow of fear over Ukrainians in the occupied regions, signaling that dissent or non-compliance could trigger persecution at any time. Here, the difference in treatment between native Russians and Ukrainians in temporarily occupied becomes glaringly evident. The latter group faces potential horrors like deportation, torture, or death, while native Russians face a more bureaucratic approach, including fines, designations as foreign agents, or criminal prosecution.

Intriguingly, reports from residents of the temporarily occupied territories suggest that Russian officials don’t always recognize the very passports they’ve distributed as valid. This results in individuals being unable to access services or benefits until they formally re-register in a recognized Russian region. Even staunch advocates of the “Russian world,” so-called “DPR citizens,” voice their disillusionment and complained about the long lines to get a Russian passport, reminiscing about the more orderly times under Oleksandr Zakharchenko, the terrorist leader assassinated in August 2019: “We have become part of Russia, but we feel like... non-Russians. We wanted law, but we got prices that even Russia doesn’t have... And you know what, under Zakharchenko, problems with the housing office were solved on the fly. Russia can’t do it? Then they should learn.”

This sentiment of discontent isn’t isolated. Official Russian statistics on passport issuance reveal a decline in enthusiasm. Residents of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions “despite the widely publicized opportunities to obtain Russian citizenship in the LDPR... for some reason lost interest in the Russian passport,” the Russian news agency RBC reported. According to their data, which was circulated by propaganda Telegram channels, “the number of Ukrainian citizens who received a Russian passport in 2022 (304 thousand people) decreased by 19% compared to 2021 (376 thousand people).”

It seems that the Russians have been unable to establish a cohesive social media campaign advocating for Russian passport adoption. Even among posts by supporters of the “Russian world,” criticism abounds. They spotlight bureaucratic hurdles faced by residents of the temporarily occupied territories in obtaining these passports and benefits, note the 2022 dip in passport issuance, and frequently lament feeling like “second-tier Russians.”

Passportization Through the Lens of Pro-Ukrainian Social Media

The issue of Russian passportization has caused a rift in pro-Ukrainian social media circles, splitting opinions into two distinct camps. The first group firmly believes in rejecting Russian passports at all costs, while the second seeks to empathize with Ukrainians residing in the temporarily occupied territories.

For the first faction of pro-Ukrainian social media users, acquiring a Russian passport is tantamount to betrayal. They argue: “These are potential collaborators and adjusters. They are very closely connected with Russians from the ‘continent’ and still have relatives in Ukraine. They complained to the occupiers about us. Now they will complain to us about the Russians. These are people lost to society. Except for the Tatars.” Notably, this stringent viewpoint is in the minority compared to the more understanding stance of the second group.

Those in the empathetic camp accentuate the coercive nature of Russian passportization and highlight its associated human rights violations. They underscore the pitfalls of holding a Russian passport – such as potential conscription into the Russian military, limited global mobility, and even non-recognition of the document within Russia.

This part of pro-Ukrainian social media users recognizes that passportization is forced and, as a rule, are sympathetic to those who agree to take a Russian passport. As an argument, they share stories of people who were forced to take Russian passports. One such account details: “In the settlements of the occupied Kherson region, Russians are humiliating the population. They threaten people with the ‘pit’ for refusing to give up their passports. The occupiers have repeatedly carried out demonstrative punishments: men were put in a bag and thrown into the trenches. Russians also use a torture chamber in Henichesk to coerce people.”

This segment of the pro-Ukrainian digital community also shines a light on how Russia exploits the passport as a mechanism of dominance. They share testimonials of individuals who have faced threats, repressive measures, educational barriers, mobility restrictions, and even the loss of humanitarian aid access, underscoring the potential peril of deportation.

“Russians are forcing pensioners from the temporarily occupied territories of Kherson region to obtain Russian passports. Those who refuse may lose their only source of income — their pensions,” social media users sympathizing with the residents of the temporarily occupied territories wrote.

The predominance of empathetic perspectives towards the inhabitants of the temporarily occupied regions indicates a resilient unity within Ukrainian society. It suggests that Russian propaganda has been largely unsuccessful in compelling the majority of Ukrainians to sever ties with their compatriots under Russian temporary control.

Repressions: Appeals, Complaints, Confessions, and Justifications

Based on interviews with ex-detainees and data gathered by the Ukrainian Media Initiative for Human Rights and the Russian human rights organization Gulagu.net, Associated Press (AP) researchers devised a map pinpointing illegal detention sites for civilian Ukrainians. This map was unveiled on July 13, 2023. AP’s findings indicate a minimum of 63 such temporary and official detention areas in the territories under occupation, plus at least 40 in Russia and Belarus, some situated thousands of kilometers away from Ukrainian borders. A UN report that AP refers to mentions 37 facilities in Russia and Belarus and 125 in occupied areas of Ukraine. Furthermore, AP journalists disclosed a Russian governmental document revealing intentions to establish an additional 25 prisoner colonies and six pre-trial detention facilities in the regions under Russian occupation by 2026.

Estimating the exact number of Ukrainians held prisoner due to the Russian repressions remains challenging because of insufficient data. However, the number is believed to be in the thousands. Some civilians face detention spanning a few days or weeks, while others have been incarcerated for more than a year. AP highlights that numerous civilians are taken into custody without formal charges. Reasons for detention vary, ranging from speaking Ukrainian to simply being young. Some are labeled terrorists, militants, or opposers of the “SMO”. In these facilities, hundreds are exploited for forced labor by the Russian military, tasked with duties like trench digging or setting up sites for mass burials. Torture is a routine occurrence, affecting a significant majority of the detainees.

To sustain such a large-scale system of repression, there’s a need for both informational and propagandist support aiming to stimulate and justify these criminal activities.

Within pro-Russian social media circles, there’s a marked increase in calls for retribution against pro-Ukrainian inhabitants of the occupied regions and commendations lauding Russian efforts in curbing Ukrainian supporters.

Calls for Reprisals Against Pro-Ukrainian Residents

These posts frequently point out the numerous Ukrainian partisans, saboteurs, and spotters who, they argue, should be dealt with severely. One post claimed: “In the garage of one of the local garage cooperatives, weapons, Molotov cocktails, NATO uniforms, and Ukrainian symbols were stored... It is necessary to carry out cleansing operations in the liberated territories constantly... The Zhduns should be demonstratively killed on the spot.” Such calls to action might be directed at ordinary individuals who might dispute, for instance, the Russian Defense Ministry’s claim that the devastation in Ukrainian cities is predominantly inflicted by the Ukrainian military. For example, “A Zhdun woman in Nova Kakhovka decided to film the destruction that, as it turns out, was caused by Russia, which entered the city without a fight, and not by the Ukrainian Armed Forces, which regularly shelled the city. We hope the author of the video will be found and treated properly. As well as her brothers in mindset.”

In the aftermath of assassination attempts on pro-Russian collaborators or sabotage against the Russian military, which is frequent in the territories under temporary occupation, there’s an escalation in calls for stringent screening processes to identify Ukrainian sympathizers. Such communications often bear a paranoid tone: “It might be worth scrutinizing Crimea too; there are plenty of those folks here as well!!!” At times, the substantial pro-Ukrainian presence is attributed to the migration from recently occupied and ravaged Ukrainian cities, as in, “Many from Mariupol have relocated to Donetsk. And they come in all sorts if you know what I mean... So, the notion about ‘local’ spotters and other Zhduns isn’t as far-fetched as some might believe...” Through such narratives, Russians sow seeds of mistrust between those occupied earlier and those occupied more recently.

Publicizing Counter-Sabotage Efforts: An Admission of Repression

Various posts detailing the arrest or even execution of Ukrainian partisans indirectly reveal Russia’s widespread repression of the local population. Many posts imply that those labeled as “saboteurs” might be any residents wanting their territory to return under Ukrainian control. An example: “A certain Valera from Simferopol hoped for Ukraine but was met by our officer. This marks the third individual from Simferopol who has been ‘re-educated’ this week.” Reports of the capture or neutralization of “saboteurs” by Russian forces often mix warnings with a sense of satisfaction about impending retribution: “We apprehended a saboteur in Crimea plotting an attack on a fuel warehouse. Nationalist correspondences were discovered on his phone and Molotov cocktails at his residence... Interestingly, in the Kherson region, currently under Ukrainian control, Zhudns who’ve been silent for six months, seem increasingly bold. They assume there won’t be consequences...”

Accusations Against Ukrainian Security Agencies

A primary tactic among pro-Russian social media users in defending their repressions is pointing fingers at Ukrainian security agencies, alleging their actions are even more severe. From this skewed perspective, any actions attributed to Ukraine supposedly render the Russian side more humane. The liberation of areas like Kharkiv in September 2022 and the right-bank region of Kherson in November 2022 became convenient occasions for the propaganda machine to spin such narratives. Pro-Russian commentators claimed that Ukraine was suppressing the pro-Russian segment of these liberated areas’ populations. For heightened emotional impact, posts equated Ukrainian forces with Nazi Germany’s punitive units, dubbing them “Einsatzgruppen” and “Kh*khlos-SS”. At the same time, fabricated narratives are being spread, claiming that the Ukrainian forces are poised to penalize a substantial segment of the local populace for their past affiliations with the Russians: “Amnesty (granted pardon, yet recorded in databases as potential offenders) will be for those who abstained from employment, schooling their children, tax-paying, or accepting aid.” These messages aim to create confusion and fear among inhabitants of both liberated and currently occupied regions. Ironically, these messages indirectly admit a strong pro-Ukrainian sentiment in areas that had supposedly voted overwhelmingly for Russian integration. The propagandists account for this disparity by championing the “humanity” of the Russian side in contrast with the Ukrainians. For instance, reflecting on the widespread celebrations post-Kherson’s liberation, they remarked: “They televised a handful of Zhduns, labeling them national heroes. The distinction between our army and your Banderite forces is that we refrained from shooting these Zhduns.” Such narratives also align with Russia’s overarching propaganda strategy, which is to demonize its enemy.

Pro-Ukrainian Social Media Users Blame People With Pro-Russian Views for Russian Aggression

Users on social media with pro-Ukrainian stances users seldom advocate for violent actions, but an increasing number of comments calling for restrictions or even deportations of the pro-Russian populace in areas that Ukraine reclaims.

A popular recommendation is to limit the voting rights of some local residents, with sentiments like, “Once Crimea and ORDLO [temporarily occupied territories of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions] are reclaimed, we should verify local Ukrainian citizenship through procedures like a language test. Those who don’t clear the verification could be designated as non-citizens, denying them the right to vote, run for office, or hold governmental positions.” Historical allusions also emerge from both pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian users. For instance, some draw parallels to World War II history, suggesting, “What if we allocated designated areas for such Zhduns, similar to how Vlasovites were treated in the former GDR? This might be a way for them to grasp the situation truly.” Yet, the predominant suggestion remains the deportation of those not loyal to Ukraine to Russia after the war: “And how many more of these crooks have not been exposed... And what else awaits us when all the territories are de-occupied, 80% of them are against Ukraine. I can’t even imagine what to do with them except to send them to Russia?”

Additionally, many pro-Ukrainian users emphasize the importance of reporting suspected collaborators to the SBU. They also frequently commend acts of guerrilla and sabotage activity in the temporarily occupied territories, assassination attempts and the destruction of representatives of the Russian occupation authorities, or sabotage against the logistics of Russian troops. Furthermore, these users often relay news, personal experiences, or rumors about repressions by the Russian authorities against residents of the temporarily occupied territories.

Generally, the posts from pro-Russian users tend to align with Russian propaganda, legitimizing the oppressive measures of the occupying forces. Meanwhile, in the Ukrainian segment, narratives of a xenophobic nature against residents of the occupied and liberated territories seem more random and inconsistent.

Issues Of Residents of De-occupied Territories: Propaganda Manipulations

During the occupation of Ukrainian territories by Russian troops, Ukrainians are forced to accept humanitarian aid, receive pensions, and take jobs as ordinary employees (in order not to collaborate with the occupiers) in order to support themselves and their families and ensure the operation of critical infrastructure. However, the Russians intimidate Ukrainians by claiming that, according to Ukrainian law, employment, humanitarian or social assistance for residents of the temporarily occupied territories is equivalent to collaboration and that after the de-occupation, they will allegedly be punished en masse for collaborating with the enemy. This contradicts another Russian propaganda thesis: “Russia is here forever!” This narrative is spread to demoralize pro-Ukrainian locals, as well as to create a sense of hopelessness and the need to accept the “new reality.”

For Ukrainian Authorities, Even Paying Utility Bills to the Occupiers is Collaboration

Pro-Kremlin Telegram channels disseminate the idea that inhabitants of temporarily occupied regions will face dire consequences once Ukrainian control is reinstated. Messages like, “Even those who merely paid rent would be demoted to non-citizenship status. Higher-ups, unless they flee, will be killed,” are rampant. Through this, the propaganda machine seeks to instill fear in Ukrainians, insinuating that irrespective of their level of cooperation with the Russians, they’d be branded traitors and potentially stripped of their Ukrainian citizenship. This exerts psychological pressure, making Ukrainians anxious about the consequences awaiting them once the territories revert to Ukrainian control.

Bureaucratic Procedures and Problems With Applying for and Receiving Pensions

Pro-Kremlin Telegram channels have disseminated instructions about pension recalculations requiring a Russian passport without a residence stamp: “For pension recalculations, residents of the DPR should furnish a Russian passport along with residence details.” They further remarked, “Since recent documents often lack registration details, there’s confusion about the required documentation.” This suggests that pension reception under Russian protocols remains an unresolved issue in territories under temporary occupation.

In temporarily occupied Melitopol, individuals receiving pensions from Russia found themselves saddled with property taxes. “You have to go to the Rashist tax office and honestly tell them what you have: a car, an apartment, garages... If the occupiers decide that you have too much property, they can nationalize some of the items on the list, take them away, or... you have to pay a certain amount of money so that they won’t bother you anymore.” This illustrates the occupation’s continued exploitation of local residents.

Pro-Kremlin Telegram channels also called for a Russian law addressing what they label as “temporarily Ukraine-occupied territories,” spanning parts of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Donetsk regions. “If it is possible not to pay pensions to pensioners in Kherson, salaries to doctors and teachers who are citizens of the Russian Federation, is it possible not to pay them throughout Russia?” This implies that when Ukraine de-occupied the Kherson region, Russia would no longer need to spend money on paying Russian pensions to people from territories it does not control.

Yet, there have been messages of gratitude to Putin for offering humanitarian aid, ensuring salary and pension payments, and organizing children’s trips to Crimea. Some even claim that life in places like Mariupol has allegedly improved post-occupation: “Residents are being provided with new housing, schools, and hospitals are being built with new equipment, and they are being ‘forced’ to receive increased pensions and financial assistance.”

“Banderites Are Persecuting Those Who Took Russian Humanitarian Aid”

“They create a picture for everyone with the humanitarian aid. But the fact that everyone in the city was being pressured for not leaving, for eating Crimean food, for the number of shell hits in the city, everyone is silent. No one even thinks of reconnecting electricity, water, or gas,” pro-Kremlin Telegram channels wrote about the Kherson region, “Only supporters of Banderites have the right to a normal life.” Ukrainian segment of Facebook also highlights inconsistencies: “They come to receive humanitarian aid from the Europeans and Americans they hate and behave as if nothing had happened!” There were even reports of threats against these residents: “People are now saying that if they are not punished legally, the only way out is to burn their houses!”

To sum up, Ukrainians in temporarily occupied regions face pension-related challenges and contend with elevated local prices compared to those in Russia. Russians are doing all they can to encourage local residents to acquire obligatory passports, potentially aiming to harness this data for orchestrated referendums. Despite these challenges, Russian propaganda paints a rosy picture of life in these areas, aiming to undermine the Ukrainian government’s image and secure local loyalty. Russians use intimidation tactics against residents of the temporarily occupied territories who take humanitarian aid to survive. By crafting tales of retaliation by Banderites, they instill fear in Ukrainians, suggesting they might fare worse post-liberation than during the occupation.

Undermining Ukraine’s De-Occupation Efforts Through Misleading Narratives

Russia’s Illusion of Rapid Reconstruction

Under Russia’s occupation of Ukrainian cities and towns, its propaganda machinery amplifies the narrative of a swift infrastructure rebuild. They claim that Ukraine has neglected these regions, necessitating Russia’s intervention to “set things right.” Case in point: Russian propagandists have emphasized their purported repair of the E-58 highway, a road Ukraine supposedly “overlooked” for three decades. This roadway spans five regions, encompassing Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Mykolaiv, areas where Ukraine faced challenges in complete access for obvious reasons. Meanwhile, the Russian House in Warsaw highlighted Russia’s supposed efforts in rebuilding Donetsk and Luhansk. Claims also circulated about Russia’s quick restoration of Mariupol. More recently, admins of pro-Russian Telegram channels broadcasted that the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant would be restored within a year by Russia. Yet, they overlook the fact that had Russia not initiated the war, no restoration would be necessary.

The primary objective of such reconstruction narratives is to tarnish Ukraine’s reputation and shake faith in the Ukrainian government. It’s insinuated that while Donetsk, purportedly rebuilt by Russia, appreciates Russian governance, cities like Kherson, untouched by “Russian progress,” are yet to feel the supposed benefits. By drawing such contrasts, the propaganda suggests that regions under Russia’s occupation thrive while areas recently liberated by Ukraine languish. The underlying message is that people from the liberated territories have not yet experienced the “Russian world” and therefore are happy to embrace the Ukrainian army.

However, in the Ukrainian segment of social media, the reality is starkly different. Users lament the devastation with posts like: “The video shows the ruins of my house. I spent my childhood there, a happy childhood. Now I’ve been deprived of it.” These accounts contradict Russia’s “reconstruction of Ukrainian cities” tales.

The propaganda’s attempt to paint a picture of benevolence through rebuilding in the occupied zones is an attempt at whitewashing. Without Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which included targeting civilian infrastructures and seizing towns, there’d be no damage to rectify. While they present themselves as magnanimous builders, they conveniently omit that their actions caused Ukrainians to lose their homes and, tragically, their lives.

Territories Liberated by Ukraine Are Falling Into Decay

The Kremlin largely denies the Ukrainian Defense Forces’ success in reclaiming territories. If mentioned, they’re labeled as “temporarily Ukraine-occupied territories.” Among these, the liberation of Kherson stands out, being the most significant city reclaimed since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Reacting to this, propagandists painted a bleak picture of post-liberation Kherson, suggesting that its civilians faced retribution from the returning Ukrainian government.

In a sample of propaganda messages, Kherson was described as a city where civilians were being killed, humanitarian aid was being stolen, and more. Through these skewed narratives, an illusion was cast that the city plunged into chaos post-liberation without electricity, water, and gas supply. Narratives like “Kherson is on the verge of a humanitarian catastrophe, a fact the Kyiv regime tries to hide, with people having to survive without water and electricity” were common in social media posts.

Indeed, post-liberation, Kherson faced infrastructural challenges. However, propagandists conveniently sidestepped the fact that Russian forces, and not the Ukrainian government, were responsible for the destruction and subsequent shelling of the city after its liberation.

Through these distorted narratives, the propaganda machinery aims to dishearten the populace, insinuating that life under Russian governance is preferable while portraying life in Ukraine as bleak, primarily due to the lack of utilities.

“During the Occupation, the Russian Military Did Not Protect Ukrainians Who Supported Russia. After the De-Occupation, Ukrainian Troops Will Not Protect Them Either”

Pro-Kremlin Telegram channels claim that locals from areas under temporary Russian occupation, despite supporting Russia, won’t find refuge with the Russian troops. After the Russians retreat, protection from Ukrainian forces is alleged to be even more unlikely.

The Russian perspective suggests that Ukrainians in these temporarily occupied areas exploit their state for personal gains, displaying contempt towards Russians. They believe Ukrainians yearn for an improved life under the Russian administration. One Telegram user opined, “He’s just a Zhdun, waiting for me, a Russian Ivan, to support him, masking his true intentions with patriotism. In truth, he’s merely a typical Ukrainian seeking a better livelihood.” This sentiment underscores the Russian irritation with Ukrainians, even those supporting Russia. The Russians anticipate a freeing of Ukrainian territories but remain reluctant to assist Ukrainians.

Sentiments on pro-Kremlin Telegram channels fluctuate. They oscillate between portraying Ukrainians in the occupied territories as opportunists seeking Russian wealth to expressions of regret over withdrawing from previously unlawfully occupied parts of Kharkiv. “The influx of refugees at the borders proves that Ukraine wasn’t awaited nor loved in the Kharkiv region,” noted pro-Russian Telegram channel admins. They express alleged deep remorse over the perceived negligence of the Kharkiv region by the Ukrainian government and Russia’s eventual abandonment of the locals they believed were awaiting their arrival. These channels seek redemption: “Our shame can only be erased through an unequivocal, glorious victory.” On July 27, 2023, at approximately 21:15, Russian forces once again targeted the Kupiansk district.

The Russian military consistently bombards Ukrainian territories and perpetrates war crimes in temporarily occupied areas. As reported by Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin, over a span of 500 days of full-scale war in Ukraine, Russian forces have killed more than 10,500 Ukrainian civilians.

Certain Telegram channels aimed at the audience in the Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine complained, “Kyiv appears apathetic as citizens evacuate. It needs territories, not the people.” They allege the Ukrainian army in the Kherson region encounters abandoned homes, furthering the narrative that “people understand exactly where they are in danger and where they can find salvation.” An example of the Ukrainian army committing crimes against Ukrainians is “the shooting of a column of civilians by the Ukrops in the Zaporizhzhia direction, which is confirmed by information from the involuntarily abandoned Kharkiv region.” However, Ihor Klymenko, the head of Ukraine’s National Police, refutes this, stating that Russian missiles struck the outskirts of Zaporizhzhia on September 30, 2022, hitting an evacuation convoy, resulting in 30 deaths and 88 injuries. Additionally, Ukraine’s Security Service confirms that in late September, in the no man’s land between occupied Svatove in Luhansk and liberated Kupiansk in Kharkiv, Russian troops opened fire on a seven-vehicle civilian convoy. “The attack claimed at least 20 lives, including 10 children,” informed Vasyl Malyuk, the acting Head of the Security Service of Ukraine.

In the Ukrainian segment of social media, an anonymous user expressed, “Those who held the Russian flag, those who turned their neighbors in to the ‘authorities’, those who were the first to run to serve the new government — [the Russians] will abandon them, they will not protect them.” Drawing parallels between Russian actions during the full-scale war and the 2014 Donetsk and Luhansk occupations, she highlights that nothing has changed. In the course of our analysis, we even found threats that people who were waiting for Russia should “crawl under the baseboard and sit there quietly in the hope that neither the occupiers nor we will notice you.” However, dominant sentiments on Ukrainian social media revolve around traitors, with a general consensus emphasizing that “those who went to the side of the enemy and began to cooperate with him should be held accountable under the law on collaboration.”

By disseminating such narratives, Russian propaganda aims to exonerate itself while demonizing the Ukrainian armed forces, portraying them as territorial aggressors who purportedly target civilians. Through mirroring tactics, Russian propaganda conceals its military’s atrocities, frequently justifying its actions against Ukrainian civilians and shifting blame onto Ukraine for civilian casualties.

Uncoordinated Strategic Communication of State Bodies Is a Service to Russian Propaganda

Following the full-fledged invasion by Russia, Ukraine exhibited commendable coordination in its information policy. Critical messages, especially those debunking Russian disinformation and essential for the safety and awareness of Ukrainians, were systematically disseminated.

Nevertheless, there were instances where conflicting information was relayed by various governmental representatives. A notable example from April 2023 is when Oleksiy Danylov, the Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, detailed a 12-step plan for Crimea’s de-occupation on his Facebook page. The plan spoke of measures like partial deportation, lustration, and voting rights restrictions for certain demographics. Danylov’s statement read: “For this Moscow garbage, I want to outline how Ukraine will de-occupy Crimea, where they and their ilk will be the number one target — to forever discourage anyone from even looking in the direction of Muscovy or opening their mouths without thinking carefully about commenting on anything related to Ukraine.” Russian propagandists leveraged these comments, distorting Danylov’s intent, to sow fear among the inhabitants of the areas under occupation. This required other officials, like the President of Ukraine’s Permanent Representative in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Tamila Tasheva, to step in and clarify: “There will be no “witch hunt”. Yes, there will be certain restrictions, but this is to be expected because people have been under occupation and influenced by hostile narratives for a long time. But we definitely don’t plan to punish hundreds of thousands of people who just lived there.”

Another communication discrepancy emerged in May 2023, involving Iryna Vereshchuk, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Reintegration of Ukraine’s Temporarily Occupied Territories, and Dmytro Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament’s Commissioner for Human Rights. The debate centered on the Ukrainian stance regarding residents of occupied territories obtaining Russian passports. Lubinets suggested that, for safety and potential ease of exit from occupied areas, residents should consider acquiring Russian passports. However, Vereshchuk opposed this view, firmly advising against such a move just a day later.

Such inconsistencies in the positions of Ukraine’s government create confusion among the residents of areas under occupation, empowering Russian propaganda to further its agenda and tarnish Ukraine’s image. A more coordinated approach and consistent public messaging by different authorities could address and rectify this challenge.

Results of the Study

The Russian propaganda machine aims to perpetuate the divisive narrative regarding residents from territories that are temporarily occupied, de-occupied, or on the frontline, causing continued controversy within Ukrainian society. This divisive technique is not novel. It dates back to 2004, when the Russians began using it. The strategy, attributed to political technologist Volodymyr Hranovskyi, involves classifying Ukrainians into categories. An illustration of this approach was the portrayal of Ukraine as composed of three different groups during the campaign for Viktor Yanukovych, who, at the time, didn’t become the president. By amplifying differences, propagandists aim to redirect Ukrainians from a united front against external aggression, pushing them instead to identify internal enemies.

The Kremlin’s objective is clear: ensuring that residents from Ukrainian territories under its control remain loyal to Russia and its appointed local heads. Exploiting the emotionally fragile state of these Ukrainians, occupiers instate stringent rules, restrict media access, and punish disloyalty. Through manipulative narratives, they push the notion that Ukraine will indiscriminately punish de-occupied territory residents—even those who didn’t side with the invaders. By propounding this, they intend to cement the belief that theUkrainian counteroffensive is dangerous for residents of the temporarily occupied territories. Additionally, they spread disinformation about deteriorating living standards post-liberation and alleged widespread persecution of the “innocent” by law enforcement. Contrarily, they laud the merits of allying with the occupiers, citing hassle-free Russian passport acquisition, no forced conscription, immediate infrastructure repair, and assured welfare benefits.

In addition, some pro-Ukrainian social media users show a lack of understanding of the residents of the temporarily occupied territories. The attitudes towards the residents of the regions in 2014 and in 2022 are different: the longer the region was under occupation, the more distrustful pro-Ukrainian social media users are towards its residents. Ukrainians who learn about the occupation from the stories of their friends or media reports find it difficult to understand Ukrainians who have lived in the occupied regions for one and a half to nine years. Due to the complexity of the coverage, there is little information about the lives of typical residents of the occupied regions — people who are not collaborators but cannot leave due to lack of money, caring for sick relatives, health problems, or other obstacles to starting a life elsewhere. The limelight, instead, usually falls on pro-Ukrainian partisans or, in less favorable instances, collaborators and traitors. These categories, unfortunately, become the emblematic representatives of occupied territories for some social media users.

A more holistic understanding is required for Ukrainian society across the contact line. They need clarity on what constitutes criminal actions during the occupation and how the nation supports residents from the different zones mentioned. While Ukraine has consistently emphasized its intention to reclaim both territories and its people, it’s pivotal that Ukrainians, irrespective of their proximity to the occupation, receive undistorted, consistent, and unbiased data about people on the other side. It’s essential they don’t perceive each other—whether from occupied areas or not—as enemies.