Українською читайте тут.

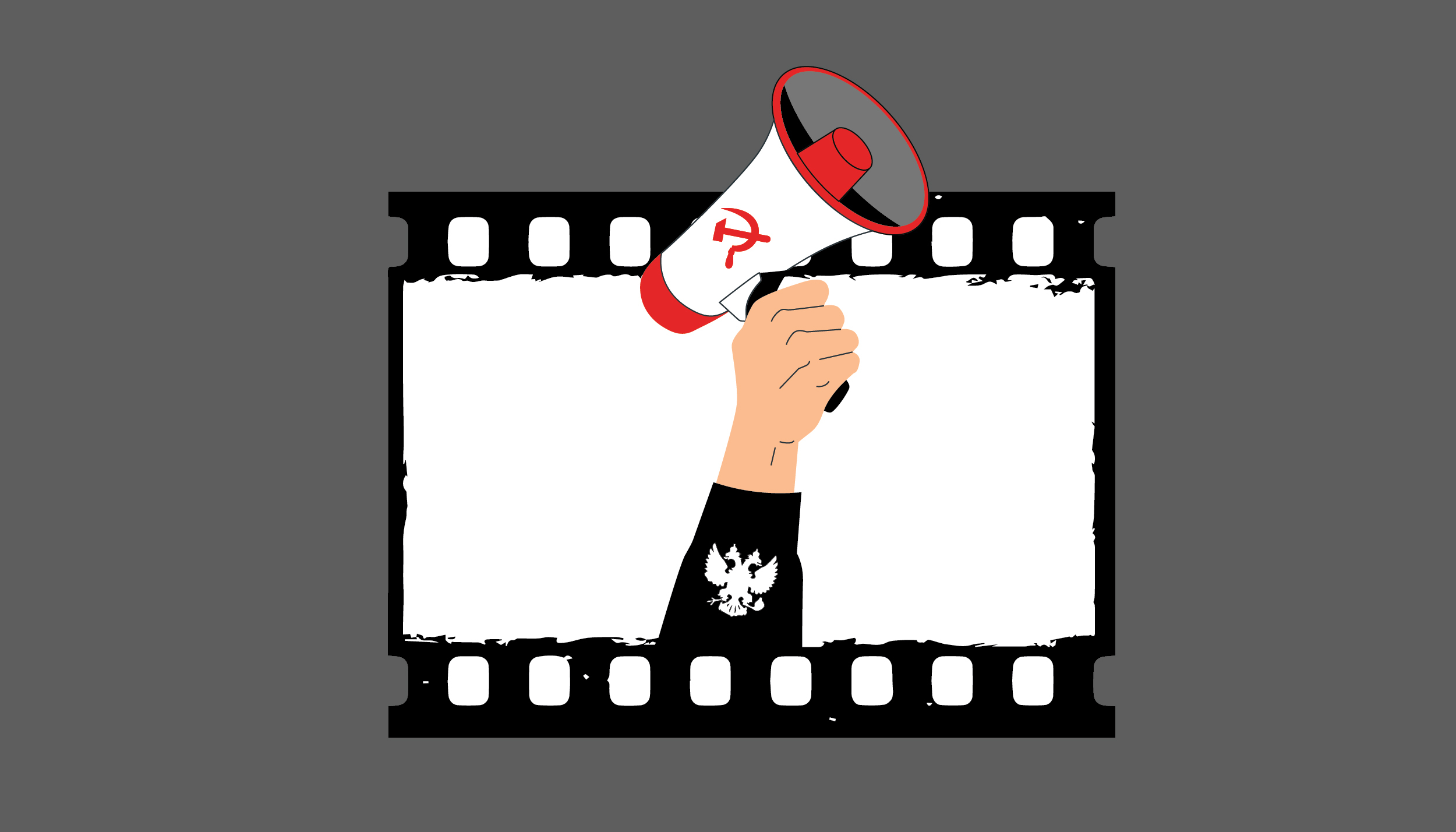

The Bolshevik system extended control over all spheres of life, including art. The notions of an all-powerful USSR and a virtuous Communist Party fighting for equality for all Soviet people were reflected in the cinema of that era. Thus, Soviet directors created a new reality for viewers. For example, according to film critic Larysa Briukhovetska, Sergei Eisenstein’s film October, which glorified the events of the October Revolution, was literally constructed from an imaginative course of events — yet even today, some scenes from the film are perceived as documentary. Also, his film Battleship Potemkin was included in the list of the 12 best films of all time and nations in Brussels in 1958, thus, the artist skillfully used his talent in the name of revolution. Like other Soviet artists, who often devoted themselves to their own calling but under party control, directors and screenwriters had to caricature and mock the enemies of Soviet power, while Bolsheviks in films appear as invincible fighters for the imminent future. Later, Soviet cinema offered an alternative reality: when millions of people in Ukraine were starving, Stalin ordered all food and grain to be taken away — film comedies showed the "fun" and "prosperous" life of peasants.

In modern times, Vladimir Putin continued the practice of oversight over Russian cinema when a year ago, he ordered films about the war against Ukraine to be shown in Russian cinemas. More precisely, documentary films intended to "fight the spread of neo-Nazi and neo-fascist ideology." According to Putin's directive, the Ministry of Defense should assist Russian documentarians in preparing cinematographic material about participants in the Russian-Ukrainian war who "showed courage, bravery, and heroism." The Kremlin spends money on war propaganda, including cinema, offering Russians their own invented reality. In it, Ukrainians are transformed into "aggressive Bandera followers" with an insurmountable desire to eradicate all Russians. However, such films, which included other genres aside from documentaries, did not appear as a result of a full-scale invasion. Russia has been consistently producing them long before the full-scale war. Finally, this helped Russians prepare the groundwork for modern war crimes and genocide of Ukrainians.

Early Soviet Cinema Period and Their Revolutionaries, Drivers of Ideology

In the Soviet book Cinema. Encyclopedic Dictionary, it is stated that the beginning of the development of Soviet cinematography occurred with the October Revolution when documentary filmmakers (still working for private studios) managed to film these events on camera. Realizing the significance of cinema art in shaping a "new" reality and spreading revolutionary ideas, the Soviet government in 1923 ordered the creation of a film studio in each republic for the production of propaganda films. The creators of revolutionary cinema became ideological innovators who influenced the development of world cinema, including Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein. For example, Ukrainian Soviet avant-garde film director Dziga Vertov often experimented with editing: splicing pieces of newsreel filmed in different years and in different places, combining them according to their theme or plot. Thus, he became one of the pioneers and theorists of documentary cinema.

During the early Soviet era, cinema experienced a surge of ideologically driven revolutionary artists. Among these, Dziga Vertov stood out for his pioneering approach, becoming the precursor of the fast-cut technique. His film Man with a Movie Camera notably topped the British Film Institute's film rating in 2014.

Vertov's works, while including masterpieces, also encompassed revolutionary propaganda (sometimes both at the same time). For instance, his 1924 silent black-and-white animated film, Soviet Toys, satirized the "bourgeois lifestyle" and the greed of the NEPmen — Soviet entrepreneurs of the time.

Sergei Eisenstein, another Soviet filmmaker, had an even more profound impact on global cinema. His film Battleship Potemkin is recognized as one of the most significant in cinematic history. Its quality was such that even Joseph Goebbels, Nazi propaganda chief, admired it for its propagandistic excellence, lamenting the lack of comparable propaganda in Germany.

Both Eisenstein and Vertov significantly influenced and transformed the world of cinema. While they supported and glorified the prevailing ideology in some of their works, this does not diminish their contributions to modern cinema.

This overview only scratches the surface of Soviet artists, focusing on key figures to understand how revolutionary artists drove the ideas foundational to the Soviet Union. For a more comprehensive exploration, the works of other artists discussed in the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy's Kinomystetstvo (Cinema Art) are recommended.

What Happened Next?

The rapid development of cinematic avant-garde, “montage of attractions,” and intellectual pursuits in new art forms dwindled. Commenting for Detector Media, Ukrainian writer and screenwriter Andriy Kokotiukha remarked that from the early 1930s to Stalin's death in 1953, Soviet cinema, including its Ukrainian-Soviet iteration, lost its global influence and was confined within the USSR. Soviet audiences were isolated from Western films and non-Soviet audiovisual art until after World War II. Analyzing the cinema of the totalitarian period is crucial to understanding how propaganda co-opted and utilized this medium for its ends.

Subsequently, cinema transitioned into a tool of pure propaganda. As Kokotiukha notes, this shift is evident in the works of director Vsevolod Pudovkin, like Suvorov (1940) and Admiral Nakhimov (1945), typifying the era's tendentious, propagandistic, and “boring” Soviet cinema.

"The failure of this film propaganda phase," Kokotiukha explains, "lies in the fact that it was the loyal subjects, not the talented, who were chosen to create these films."

The research paper Socialist Realism of Soviet Cinema: In Search of an Ideological Paradigm highlights that from the 1930s, party control over film production intensified, turning Soviet cinema into a vehicle for mass agitation, propaganda, and the reinforcement of totalitarianism and Stalinism.

Larysa Briukhovetska, a film critic, editor-in-chief of the Kino-Teatr magazine, and senior lecturer at the Department of Cultural Studies at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy curated a selection of Soviet propaganda films for the Den online newspaper. Her list includes October (1927), Wedding in Malinovka (1967), The Rich Bride (1938), and P.K.P. (Pilsudski Bought Petliura, 1926).

The Rich Bride, directed by Ivan Pyryev, showcases his status as a quintessential Soviet propagandist director. Celebrated by Stalin and awarded numerous Soviet accolades, Pyryev gained fame for his portrayal of an idealized, "happy" collective farm life, which soon epitomized the Stalinist period's cinema.

This era's film art thus demonstrates that propaganda was already an established ideological tool for nurturing and sustaining a totalitarian regime. You can learn more about other directors of this period and their works here.

Times Have Changed, But Not The Techniques: Ukrainians in Russian Films

Today, Russia continues to employ cinema as a tool for propaganda, manipulating historical narratives, crafting false portrayals, instilling stereotypes, and vilifying those deemed as “enemies” of the state. In 2015, Ukraine reacted by amending its law “On Cinematography," which led to the prohibition of 579 Russian films and TV series. This ban targeted content that either glorified Russia, disparaged Ukrainians, or featured actors known for their anti-Ukrainian sentiments. Among the banned materials are films positively depicting Soviet state security officers, those justifying or legitimizing the occupation of Ukrainian territory, and films produced or initially released after January 1, 2014.

Despite these measures, Russia persists in producing and distributing propagandistic content, both domestically and internationally.

Journalist Olena Kozar observes that contemporary Russian cinema, tailored to Moscow's directives, often caricatures Ukrainians as "Banderites," "Nazi supporters," and "fools in wide trousers." This systematic stereotyping serves to dehumanize Ukrainians and other non-Russian groups, warping reality and coaxing viewers into accepting an alternate, distorted version of it.

Film producer Ilya Gladshtein points out that Moscow's films also indulge in "toxic nostalgia," persistently echoing sentiments about the "benevolent Soviet Union" and the "triumphant Great Patriotic War." Such narratives are designed to propagate the notion of "one people," mentally merging Russians and Ukrainians.

To learn more about how Russian propaganda instrumentalizes history for its own benefit, read here.

In a detailed analysis of anti-Ukrainian propaganda in cinema, it's noted that Russian films predominantly focus on military and patriotic themes, which are favorably received by the Kremlin. This research highlights a shift in the portrayal of Ukrainians in Russian cinema post-USSR. Initially depicted as naive and less intelligent "little brothers," indicative of an underlying message of Ukrainian inferiority (a portrayal style used by director Pyryev), contemporary films have shifted to showing Ukrainians as deceitful, cruel, and still uneducated enemies.

The study also categorizes the portrayal of Ukrainians in three distinct periods: pre-2014 military aggression, during the aggression, and within the context of the full-scale invasion. Focusing on the pre-2014 era, the 2010 film We Are From the Future 2 is referenced. This military sci-fi movie involves time travel by Ukrainian and Russian characters to the Second World War era. The film is partly set in contemporary "fascist" Ukraine, where people dislike Russians, sing rock songs under Nazi flags, and drink all the time. However, even after changing the setting from contemporary Ukraine to 1944, the characters' environment remains the same as they are surrounded by the same Ukrainian "nationalists," murderers, and drunks.

Political analyst Pavlo Bulhak, in his article for Detector Media, elaborates on the portrayal of OUN-UPA soldiers in the film. These soldiers are shown as bandits and murderers of Ukrainian civilians, depicted as dirty, uniformless, and led by a commander (played by Ostap Stupka) who constantly drinks moonshine.

A pivotal scene in the film involves the Ukrainian protagonists, transported to the past, being coerced to prove their loyalty to the UPA by executing fellow Ukrainians accused of collaborating with Communists. The scene depicts a pit containing Red Army soldiers, two main Russian characters, Ukrainian women and girls in national dress, and elderly Ukrainians.

Here, a character named Grandpa Mykola, an UPA member, says, “There are no people here, only communists or those who helped them. So show us that you are for a free Ukraine."

As the captives plead for mercy in Ukrainian, the protagonists hesitate, ultimately refusing to comply. The UPA members then execute everyone in the pit themselves. Bulhak concludes by stating that this portrayal aligns with the typical depiction of gangs as portrayed in Soviet and now Russian historiography.

This is how the movie portrayed "hostile" Ukrainians. The hero says: "Muscovites! Hang yourselves!" Screenshot by Zagin Kinomaniv

In general, the film endorses the myth that Ukrainian nationalists widely supported the German invaders. Both the SS Division Galicia and the UPA soldiers are portrayed in a rather exaggerated, caricatured manner. The depiction of UPA soldiers in the film is particularly negative, showing them as bandits who terrorize civilians.

Following the film's release, the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture's Department of State Regulation of Film and Video Distribution banned it, citing that it stokes "ethnic hatred and grossly distorts historical facts.”

Another film, Russkiy Harakter (Russian character), made in 2014 amidst the occupation of Crimea, is noteworthy. It's a common tactic of the aggressor nation's propagandists to use historical and ethno-cultural "reasons" to defend their actions, asserting that Crimea has "always been an integral part of Russia." This film doesn't shy away from such assertions.

The plot centers around a Russian naval officer visiting his grandfather in Crimea in 2013, only to discover he's been murdered by "Banderites." The local "police" covers up for the "Banderites" because they are backed by the Ukrainian government, which is also run by American oligarchs.

This is the movie's portrayal of "Banderite bandits." Screenshot from a YouTube channel of a pro-Kremlin media outlet

The film frequently pushes the narratives "Crimea is ours," "oppression of Russian-speaking people," and "the nefarious nature of Ukrainians who have been speaking Russian all their lives but suddenly remembered that they were Ukrainians."

The film showcases Crimea's "belonging" to Russia through constant references like "our land" or "my land." The protagonist, before visiting Crimea, ambiguously remarks, "For some, Crimea is Ukrainian; for others, it's Russian." It was the Russian officer's "second homeland," where he met his childhood friend and where they often sailed as children. Of course, the characters mentioned that this sea was "ours." But over time, that friend would turn into a Ukrainian "policeman" who would chase the Russian out of Crimea, saying, "You, my friend, are nobody here."

The film escalates to a confrontation between the protagonist and "Ukrainian nationalists," with scenes of violence and chaos. Despite the Ukrainians seemingly gaining the upper hand, the appearance of the "little green men" implies a secure future for the peninsula under Russian control.

The protagonist of the film could not tolerate such lawlessness, leading him to fight with the "Ukrainian nationalists" on the side of the people's "militia." The Ukrainians injure a priest, who calls for "public peace" when he falls down, and show the deaths of brave "militia" members. It would seem that the Ukrainians are gaining the upper hand and succeeding in driving the Russians out of Crimea. But then suddenly, the valiant "little green men" emerge seemingly out of nowhere, and the peninsula is "definitely safe" now.

Final shots of the "movie epic". Screenshot from a YouTube channel of a pro-Kremlin media outlet

Certainly, the film is a piece of propaganda and does not warrant any artistic accolades. It's just one of many low-quality productions frequently produced in Russia. Another such propaganda film is The Crimean Bridge. Made with Love!, directed by Margarita Simonyan, the chief editor of the propaganda TV and radio company RT, and her spouse Tigran Keosayan. The movie, however, is mediocre at best, presenting itself as an "apolitical comedy" about a philandering bridge builder who eventually finds love. Despite the attempt, the film was a commercial failure, only earning half of its budget, which was financed by both the state and Arkady Rotenberg's company, the very one that constructed the bridge. Intriguingly, the filmmakers drew inspiration from Soviet cinema, specifically Pyryev’s Cossacks of the Kuban. Yet, in a seemingly apolitical film, there is a portrayal of a Crimean Tatar who justifies the Stalin-era deportation of Tatars.

Merely 18 months following the onset of the full-scale invasion, Russian propaganda produced Svidetel, a movie about the so-called “special military operation” that premiered in Russia on August 17, 2023. This film marks the first feature-length depiction of the Russian full-scale invasion that began on February 24, 2022. As expected, it depicts the Ukrainian military as merciless "Nazis" who engage in torture and murder of their own people. One scene even shows a soldier wearing a T-shirt adorned with Hitler's image. The Guardian highlights additional scenes, including a Ukrainian commander purportedly carrying a copy of Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler’s book, and other Ukrainian soldiers pledging allegiance to the Nazi party leader.

The film's protagonist, Daniel Cohen, is a renowned Belgian violinist. He arrives in Kyiv to perform at a private event just days before the full-scale invasion in February 2022. Accompanied by his manager, they find themselves entangled in "dramatic events" that profoundly alter his life.

Screenshot from the trailer. Detector Media

The film trailer describes its main aim as exposing the alleged crimes of Ukrainians: “The events of the Special Military Operation lead the musician to the Ukrainian village of Semidveri, where he witnesses inhuman crimes and bloody provocations. Now his main goal is not only to survive but also to bring the truth to the whole world. After all, the truth is stronger than fear."

In an article for Detector Media, art critic Lena Chychenina interprets the fictional village of Semidveri as a stand-in for Bucha. In Bucha, Russian forces are widely reported to have committed systematic war crimes, including abuse, rape, and murder of civilians during the occupation of the Kyiv region in 2022. Ultimately, this is a typical propaganda tactic of mirroring, where Russians project their own actions onto Ukrainians, despite clear evidence of the actual perpetrators.

The film, supported by the Russian Ministry of Culture through a competition for “feature-length films reflecting major geopolitical and social changes in modern Russia”, received direct involvement from the Russian Ministry of Defense. With a budget of 200 million rubles, as reported by The Guardian, Witness, unlike Russkiy Harakter, is targeted at international audiences through its original English language production. This international focus might explain its poor performance at the Russian box office, along with criticisms from Russian film critics who labeled it a “dull” propaganda piece.

Propaganda often relies on oversimplification and emotional manipulation, both actively employed by Russian directors. It portrays Russians as inherently good and Ukrainian military personnel as criminals, a narrative aligning with the Kremlin's interests. The Russian public is essentially compelled to consume such content, often laced with misinformation aimed at influencing perceptions first and foremost.

Comparing Soviet-era cinema with contemporary Russian films, Andriy Kokotiukha notes a commonality: both are derivative, echoing Western models. They are often either reimaginings or direct remakes of Western films, with Piriev's works on "happy" collective farmers cited as an example.

However, unlike Soviet cinema, current Russian films lack talent and originality, resulting in mediocrity. These creations are not dedicated to art but to appeasing leadership.