Detector Media analysed nine thousand posts in the Russian and occupation segments of Telegram to determine how Russian propaganda was preparing for the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia.

The study was conducted by Ira Riaboshtan, Oleksiy Pivtorak, and Olha Bilousenko

Detector Media routinely analyses Russian disinformation in the Ukrainian and Russian segments of social media. During this time, we, like other researchers of Russian propaganda, have determined that Russian military operations are almost always preceded by information operations. For example, the myth of ‘eight years’ started spreading before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In addition, according to Microsoft and the State Special Communications Service of Ukraine, Russia’s cyber attacks on Ukrainian institutions are often linked with military offensives by Russia. That is, the Kremlin is preparing an informational and virtual background for its operations, including war crimes. Among these crimes are the deportation and illegal adoption of Ukrainian children into Russian families. Until February 2022, there was almost no information in the media about the forced removal of children from the occupied Ukrainian territories to Russia. Instead, from the first months of the full-scale invasion, these crimes began to be recorded in various cities occupied by Russia. Therefore, Detector Media decided to investigate how Russian propaganda paved the way for this crime, as well as how it supports and promotes it now.

Methodology

Detector Media analysed almost nine thousand posts in the Russian and occupation segments of Telegram, provided by LetsData and Semantrum. By the Russian segment, we mean posts of profiles, pages, groups, and channels that are located in Russia or indicate Russia as their location. By the occupation segment, we mean groups and channels whose geolocation is defined as both Ukraine and Russia, but their audience is temporarily occupied Ukrainian territories. Read more about this here.

Monitoring period: summer to autumn 2022.

Methodology of data acquisition and processing: read here.

Identifying ‘children of the Donbas’ according to Russian propaganda

In the information war against Ukraine, Russia often uses various vulnerable groups for its manipulations. Previously, Detector Media has already conducted research on Russian disinformation concerning Ukrainian refugees, gender, and LGBT. Unlike previous studies, in this one, we focus on Russian disinformation not about all Ukrainian children but about a particular demographic — the so-called ‘children of the Donbas’. Russian propaganda campaigns often use this category to target Russians or Ukrainians living in Russian-occupied territories. However, the consequences of this campaign affect the whole of Ukraine. One of them is the forced deportation and abduction of Ukrainian children from the occupied territories and the illegal adoption of these children in Russia.

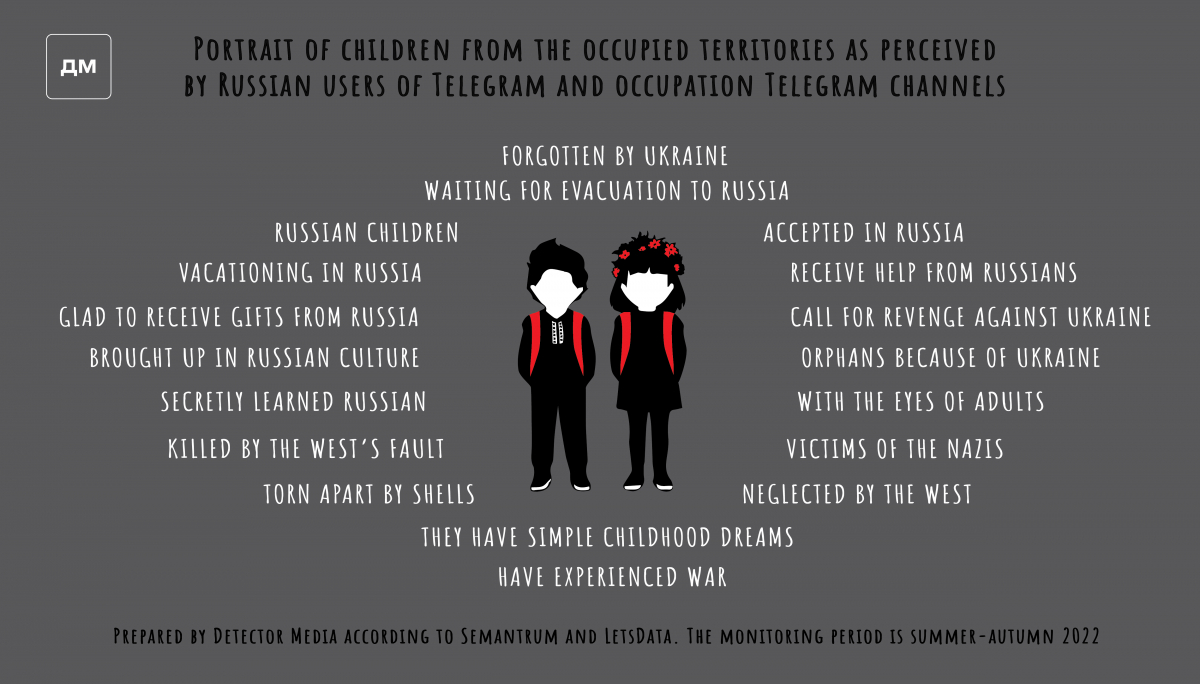

The topic of ‘the children of the Donbas’ began to circulate in parallel with the myth of ‘8 years’ during which Ukraine allegedly ‘shelled Donetsk’, ‘bombed the Donbas’, and ‘killed Russian people in the Donbas’. This gave Russians and Russian bots in various social media another ‘argument’ in the debate about the reasons for the start of the full-scale invasion. The broader definition of ‘children of the Donbas’, according to Russian propaganda, includes all people under the age of 18 living in the occupied parts of the Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson, Zaporizhia and Kharkiv regions who allegedly ‘suffered from the actions of the Kyiv regime’ and whom Russia ‘came to liberate’. A narrower definition is children from the occupied areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions who ‘have never lived in peace’. The latter definition was especially often used in late summer 2022 when they wrote about the beginning of the new school year and primary school students who ‘spent their entire childhood under shelling from Ukraine’.

As for the role of Russia in the fate of the ‘children of the Donbas’, Russian propaganda says it doesn’t begin until 2022 — ‘children in the Donbas have been dying for a long time before the ‘special military operation’, so Russia has nothing to do with it’. That is, the myth about ‘they are not there’ is still alive.

Meanwhile, after 24 February 2022, when the Kremlin finally acknowledged that Russian troops were in Ukraine, they began to use another tactic — comparison: when Russia ‘supports, gives, accepts, honours the memory of Donbas children’, and Ukraine ‘kills, burns, shells’, etc. This is a classic form of manipulation, which has long been used by Russian propaganda. However, currently, when Russia officially recognises its presence in the occupied territories and a full-scale war is going on in Ukraine, this comparison has intensified.

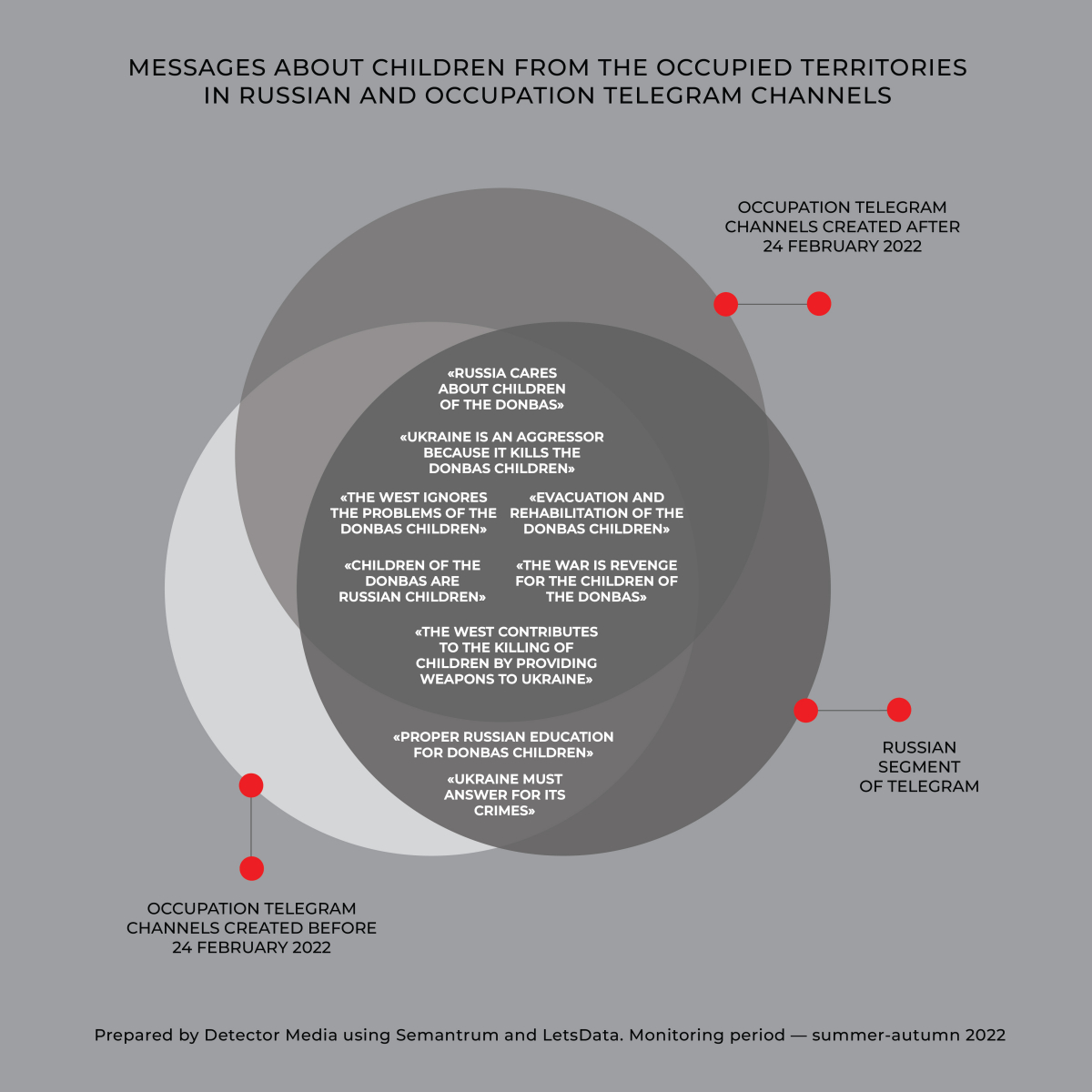

The difference between the Russian and the occupation segment of Telegram

The main difference between the Russian and the occupation segments was the tone of voice — communication style when interacting with users. In the Russian segment, it was emotions, while in the occupation segment, it was ‘officiality’.

The Russian segment of Telegram can be called aggressive. This aggression was manifested both in the attitude towards Ukraine and in the justification of Russia’s actions. It often came from individual users through public Telegram chats or personal blogs. The main tool was emotions. This results in more hostile rhetoric than in the occupation segment regarding the actions of Ukraine and the West. This segment primarily emphasises the message about the war against Ukraine as ‘revenge for the children of the Donbas.’ In general, the range of ‘justifications’ and ‘explanations’ of the reasons for the full-scale invasion was wider in the Russian segment. Moreover, it was for the Russian audience that the concept of ‘Donbas children are Russian children’ was formed, utilising which they tried to ‘convince’ Russian users of the ‘need to intervene’ in the affairs of Ukraine.

In addition to the Russian segment, we studied the occupation segment, dividing it into two periods — before 24 February (Telegram channels that were launched before the full-scale invasion) and after 24 February. No difference in rhetoric was recorded between them, only geographical expansion, because after 24 February 2022, many Telegram channels were created in the occupied parts of the Zaporizhia, Kharkiv, and Kherson regions. The occupation segment often promoted pseudo-official statements and messages from the occupation authorities or Russian officials. In most cases, they were used as ‘arguments’ to support the thesis that ‘Russia cares about the children of the Donbas’ or about the ‘evacuation and rehabilitation of children of the Donbas’. At the same time, in the occupation segment, the connections between the networks of Telegram channels are more obvious, namely: when one post is reposted more than 100 times without any changes, trying to establish a certain point of view among their readers through frequent exposure.

Based on the example of this study, we can say that for the Russian audience, Kremlin propaganda uses a set of tools that appeals mainly to emotions. Methods of this type are likely to influence the aggressiveness of Russian users who cannot reasonably explain their claims — they receive information through emotions at the level of concepts, not facts. Whereas the approaches of Russian propaganda to the occupied territories of Ukraine, although trying to evoke negative emotions towards the Ukrainian government or the West, tend to be more factual.

’Ukraine is an aggressor because it kills Donbas children’

’Ukrainian militants kill defenceless people. Not looking in the eyes, but suddenly, just shooting them in the back. Neo-Nazis steal not only the blood of the Donbas families but also the most valuable thing they have — the future of their families,’ wrote pro-Russian social media users. Thus, trying to portray Ukraine, which allegedly murders children in Donbas ruthlessly, as the aggressor instead of Russia. This message comes from several narratives at once. In particular, the one that claims that Ukrainians are Nazi punishers who seek to destroy the so-called people of Donbas. This message also fuels the narrative that Ukraine has been killing civilians there for ‘8 years’, destroying infrastructure, and encroaching on the sacred — the lives of children. They are no longer able to remember life without the sounds of explosions and the constant fear, according to pro-Russian users. They tried to establish the ruthlessness of Ukraine with posts about Ukrainian soldiers who were ready to shoot children in the Donbas in the legs if they interfered with them, etc. ‘An Azov soldier threatened to shoot a child in the legs. In the basement of the school, where adults and children were gathered, an armed Azov militant came to us and started talking some propaganda nonsense. We laughed a little. And he said: if you laugh again, I will shoot you in the legs, you will be jumping here. And to a child of six years old, who came behind his back, too,’ the statement read.

In early March 2022, the Russian and occupation segments of Telegram spread the message that Ukraine ‘intends to abduct and take to an unknown destination’ children from the occupied territories. The short-term surge of such messages was replaced by the ‘classic’ message that Ukraine for eight years ‘has been taking away the childhood of children from the occupied territories who had to hide from shelling and suffered from the cruelty of Ukrainians’. To reinforce the message that children from the occupied territories cannot have a childhood, documentaries were shown about children playing near explosive devices: ‘80 mm. It is big, you can’t take it. And this is a small one. This is a mortar round’s tail. Here it is, a mortar bomb’ — these are the words of Russian documentary filmmakers to describe the images of children living in the occupied territories.

In this way, the Russian propaganda machine tries to shift the responsibility for the crimes of the Russian army on the territory of Ukraine and, by blurring the boundaries, to justify Russia’s offensive against Ukraine, which began in 2014 with the seizure of Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. However, while spreading these messages and manipulating the fact that children of the Donbas no longer remember peaceful life, propagandists do not mention that the war would not have happened without the decision of the Russian leadership to attack Ukraine, motivating the attack first by the so-called protection of Russian-speakers, and later by ‘denazification’.

’Children of the Donbas are Russian children’

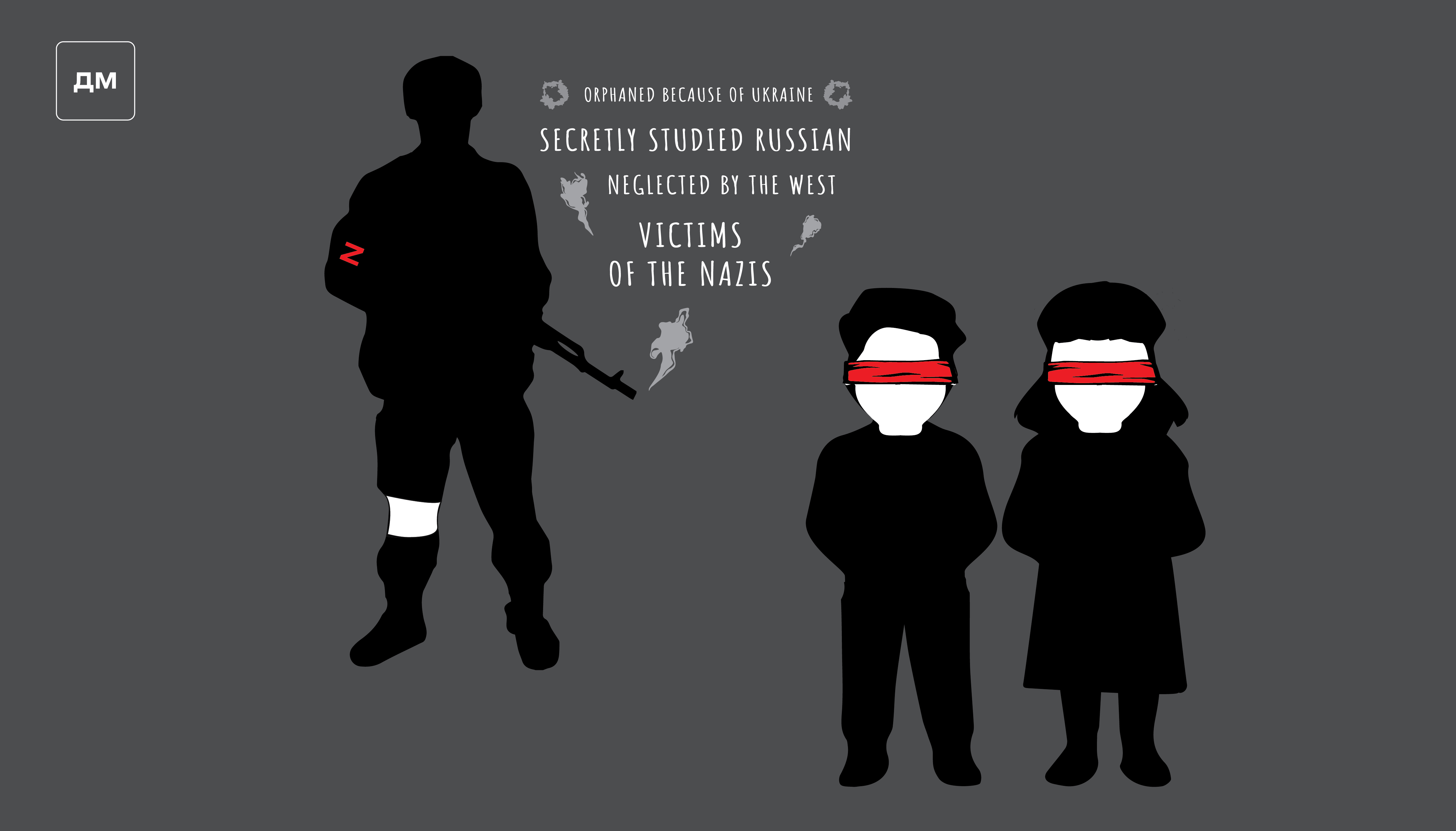

In this case, Russian propaganda continues the practice of separating the age group into separate categories for further use, depending on its goals. This message was eventually used as an argument for other, broader messages about the so-called Russophobia, ‘Nazism in Ukraine’, etc. Mostly the concept of ‘Russian children of the Donbas’ was spread through personal stories of people from the Donetsk or Luhansk regions, which is a powerful manipulative tool. It contributes to better absorption of the message than just a post on social media. In such stories, it was often described how ‘children were waiting for Russia to save them’, that they were ‘afraid to talk about their pro-Russian position’, that they ‘secretly studied Russian because it was banned’, etc. Finally, these stories lead to the fact that Russia acts as a kind of ‘saviour of children’.

This notion was promoted mainly by users of the Russian segment of Telegram. In contrast to the occupation Telegram channels, nearly no record of its spread can be found. That is, the concept of the ‘Russian children of the Donbas’ is an explanation for the Russian audience about the reasons for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

’Evacuation and rehabilitation of Donbas children’

During the study, analysts recorded a large number of messages aimed at justifying the Kremlin’s actions — the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia or to the Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia before 24 February 2022. At the same time, the Russian social media segment spread messages about simplifying the adoption procedure for ‘Donbas children’ and the ‘benefits’ that Russian citizens can receive if they ‘adopt a child from the Donbas’.

All the previous concepts in one way or another influenced the Russian and pro-Russian audience, trying to convince them that ‘children of the Donbas’, or even more broadly, Ukrainian children, are allegedly in danger, so they need to be ‘saved’. At first, most of the messages focused on opposing the arguments ‘children are not safe in the Donbas’ and ‘it is safe in Russia’. Over time, the geography of the message expanded to the Sumy, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions. For example, pro-Russian contributors spread the message that ‘children from the Donbas are used to hiding from shelling and spending the night in the basements of their houses without light and water’. They also promoted messages about shelling near children, about ‘the eyes of these children with an adult look, they had to go through too much’ and so on. On the other hand, they wrote about Russia as a ‘safe place’ without shelling, where ‘children of the Donbas are happy in peaceful Moscow’. After the creation of a stable set of arguments in this vein among the Russian and pro-Russian audience, the Kremlin propaganda began to write even more about the deportation of children from the occupied parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions to Russia. At first, they mostly wrote about children from orphanages. For example, the number of posts about children being taken away has increased since February 2022: ‘14 children <...> went to Taganrog, where all the pupils of the municipal budgetary institution ‘Children’s Social Centre of Donetsk’ have been evacuated since February this year’. At the same time, they promoted the concepts ‘Russia unites families’, ‘Russia is a new home for children of the Donbas’, etc.

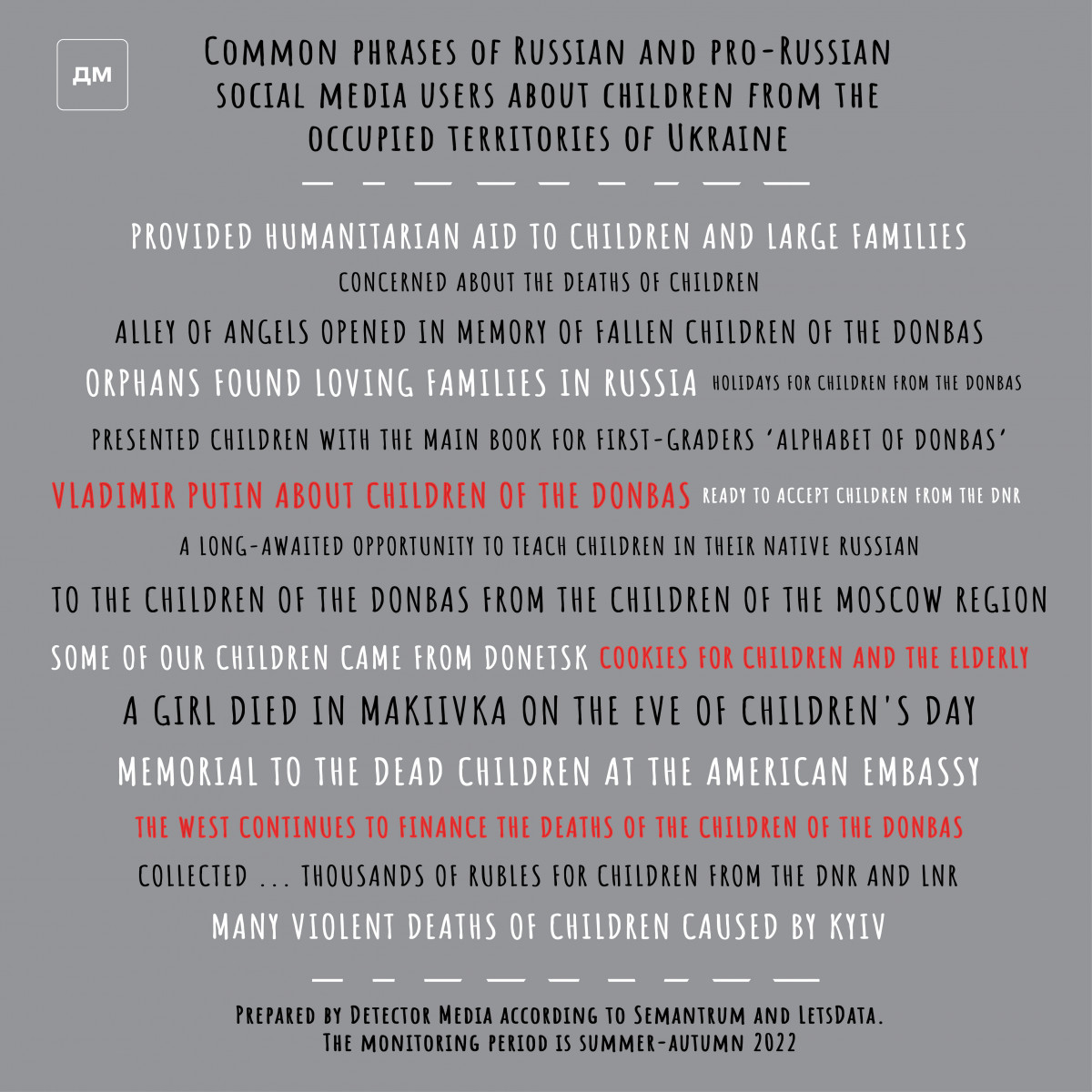

The next stage began in the summer when Russian and occupation Telegram channels wrote that with the assistance of Russian officials and deputies, children from the occupied regions of Ukraine began to be taken on vacations. The ‘most popular’ destinations are occupied Crimea or Russia itself. For example, ‘children from the Zaporizhia region rested and improved their health in different cities of Russia’, ‘Melitopol children went on vacation to the southern cities of Russia’, ‘the first shift for Yamal children and children from Volnovakha was completed at the Mandarin summer camp’ and so on. Another reason for the relocation of children from the occupied territories was allegedly treatment or rehabilitation: ‘full psychological rehabilitation of children from Mariupol, who <...> went on a big trip to Russia’, ‘16 children from the DNR are going to Moscow for rehabilitation’, ‘a boy from Kherson was sent to Russia for treatment’, etc. During the summer, occupation Telegram channels were full of such messages: both those that mimic local groups or media, and those that pretend to be communication channels of the occupation authorities. Russian propaganda spread such messages in an attempt to reinforce the message that ‘Russia helps and saves children’. The consequences of one such ‘trip to the camp’ were described by the American edition of the NYT, which published the story of a resident of the Kharkiv region, whose child went to Russia in August to a free children’s camp, allegedly to be safe from constant shelling. As of November 23, when the NYT story was published, the child had not returned to her mother. In another story told by Ukrainian Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets, on December 21, Ukraine returned three children who had been illegally taken from the Kharkiv region to the Medvezhonok children’s camp in Gelendzhik, Russia. The Washington Post told the story of a family from Mariupol: a child was taken from his parents and taken to occupied Donetsk, allegedly for treatment, where they attempted to give him to a Russian family. Only in the first month of the full-scale war, Russia abducted more than two thousand Ukrainian children. At that time, Advisor to the Commissioner of the President of Ukraine for Children’s Rights and Child Rehabilitation Daria Gerasymchuk reported that law enforcement officers had registered proceedings on the illegal transfer of more than two thousand Ukrainian children to Russia by the Russian invaders. Forced deportation violates international law, human rights, and the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Meanwhile, Russia launched a campaign to encourage Russian families to adopt children from Ukraine. Occupation Telegram channels promoted the message that Russia was adopting a new draft law on adoption, which simplifies the procedure for ‘obtaining Russian citizenship for children of the Donbas’, opens schools for foster parents, and launches hotlines for those wishing to ‘adopt children of the Donbas into their families’. On the other hand, the Russian segment of Telegram most actively promoted the notion that ‘foster parents will receive increased payments for adopted children’.

In light of this, a large number of news that Ukrainian children ‘find new families’ in Russia began started being published in the media of the occupied territories: ‘Dmitry and Tatyana, a family from the Moscow region, have adopted nine siblings from the Donetsk People’s Republic’, ‘27 orphans from the DNR arrived in Aprelivka, under temporary care in their new families’, etc.

There are more and more instances of Russian officials being featured in news reports such as, for example, the one about 27 children from the occupied Donetsk region who were met by the governor of the Moscow region Andrey Vorobyov and the Commissioner for Children’s Rights in Russia Maria Lvova-Belova. This Lvova-Belova often appears in the news about the deportation of Ukrainian children. She has been sanctioned by the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, Switzerland, and the European Union for promoting the forced adoption of Ukrainian children into Russian families. Moreover, she is directly involved in these abductions, and in addition to facilitating the deportations, the so-called ombudsman ‘adopted a boy from Mariupol’. This story received extensive coverage by both Russian media and Russian and pro-Russian Telegram channels. It became a kind of propaganda aimed at inciting and encouraging Russians to follow the example of the Ombudsman.

Therefore, Russia does not deny its involvement in the deportation of children from Ukraine, on the contrary, it uses this topic for promotional purposes. Russian propaganda hardly reacts to the accusations of deportation and genocide. Although from time to time it states that ‘Russia returns evacuated children to Ukrainian guardians’.

As of December 22, 2022, the Ukrainian authorities have verified that more than 13 thousand children were forcibly removed from Ukraine by Russia. According to open sources released by Russia, published by the Children of War website, as of the end of 2022, Russia deported 721 thousand children. At the same time, Dmytro Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, says that the number of Ukrainian children deported to Russia could be hundreds of thousands.

’Russia cares about children of the Donbas’

This is one of the most popular notions spread in the Russian and occupation segment of Telegram. It was often supported by official-looking posts promoting Russian officials. Helping those who live in or have left the war zone has become one of the ways to provide ‘noble’ motives for Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. In addition to ‘evacuation and vacation trips’, children who arrived in Russia with their families were offered vouchers for food or various benefits: from the Russian Red Cross to local state administrations.

At the same time, Russia continued to create the image of ‘caring’ for children from the occupied territories by Russians who send them aid or bring them gifts. For example, ‘children of the Donbas from the Moscow region’ received a truck of ice cream. However, most often the Russian ruling party ‘United Russia’ is mentioned in the context of collecting and delivering aid or gifts to those who remained in the occupied territories. Such publications create the impression of implicit or explicit campaigning for a political force that has had a majority in the Russian State Duma since 2003 and, accordingly, is involved in strengthening Putin’s power and establishing a militaristic mindset in Russian society.

’Proper Russian education for Donbas children’

Educational ‘integration’ is one of the aspects of Russian propaganda in the context of Russia’s occupation of Ukrainian territories. Even before 24 February, Russia spread the narrative of alleged Russophobia, fueling it with fakes about ‘banning the Russian language’ or ‘nationalist literature’ in libraries and schools. For example, in 2021, a manipulation was being spread that in one of the schools in the Odesa region, Russian-language books were allegedly ‘demonstratively thrown out into the street’. Therefore, when speaking of ‘children of the Donbas’, Russian propaganda has resorted to familiar tools. For example, in April, there was a report about children from the territories occupied by the Russian military after 24 February: the Federation Council of Russia found out that not all children in the occupied territories know Russian at the level necessary to study with Russian textbooks. At the same time, they promoted stories about parents who secretly taught their children Russian despite the ‘nationalist education’ of the Ukrainian educational system. In fact, no one excluded Russian from the schooling system in Ukraine, let alone restricted its use in private life. As of April 2022, 424 schools were offering full or partial Russian instruction.

In June, there were reports that children in the occupied territories would go to schools with Russian language instruction. For this purpose, as Russian users wrote in July, teachers and textbooks were brought in from Russia. ‘We will teach children according to the Russian program. Since these settlements were under occupation for eight years, it is not clear what they were taught. The Russian language was oppressed, banned. History went inside out,’ said the so-called head of the occupation administration of the Novoazovsk district of the Donetsk region Oleg Morgun.

Another tool was comparison. ‘The children of Ukraine are hiding in basements in Kyiv and Kharkiv, while the children of the Donbas will go to new modern schools on September 1,’ Russia wrote in early July. At the same time, they spread the idea about Russia’s intentions to provide financial assistance to the ‘children of the Donbas’. In particular, Russian propaganda circulated the statement of the former chairman of the State Duma of Russia Vyacheslav Volodin, who proposed to develop mechanisms to pay children of the Donbas ten thousand Russian rubles in order to prepare for the school year.

Very little was written on social media about what happens to Ukrainian schoolchildren who end up in Russia. Instead, there are reports about school graduates in the occupied territories who were given state-funded places in the subjects of the Russian Federation, in particular in Bashkortostan. Some posters in the Russian segment seemed dissatisfied with the fact that applicants from Ukraine had privileges, so they complained that Ukrainian children were taking Russian children’s state-funded places.

According to social media posts, the process of transition to ‘Russian standards’ of education began long before the illegal ‘referendum’ in these occupied territories. Throughout this process, the main role was played by representatives of the occupation authorities and Russian education officials.

Russia accuses Ukraine of abandoning everything Russian, but in fact, it is Russia that, as soon as it occupies a part of Ukraine, immediately introduces its own system of education, destroys Ukrainian textbooks, etc. Instead, the gradual transition to the use of Ukrainian as the main language of education in Ukraine began in 2017 with the new version of the Law ‘On Education’. Schools had until 2023 to switch to Ukrainian as the language of instruction. Moreover, primary school education was to be offered in the languages of national minorities. Russians called the new education rules discriminatory. The practice of switching all schools in occupied territories to Russian is not consistent with such rhetoric.

’The West ignores the problem of Donbas children’

This was one of the main ‘claims’ of Russian propaganda to the ‘collective West’. Depending on specific examples, the West was understood as international organisations (such as the UN or UNICEF), a certain state or a group of countries. As for the latter, it was mainly about the so-called Anglo-Saxons, by which Kremlin propagandists usually mean the United States and the United Kingdom, situationally adding to this list even Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Detector Media wrote about the use of ‘labelling’ tactics earlier, when it investigated which countries Russian propaganda covers in the context of the war in Ukraine. In particular, the posts of users from the Russian and occupation segments of Telegram stated that ‘Anglo-Saxons should pray for the children of the Donbas’, that ‘the world should see [the atrocities of the Ukrainian authorities against children] and finally wake up’, that ‘no one in the West stood up for the children of the Donbas, condemned the crimes of Ukrainian nationalists’, etc.

International organisations were written about in a similar context, accusing them of allegedly ignoring the problem. Most often, Russian and pro-Russian users expressed such condemnation when Russia appealed to the UN and UNICEF ‘regarding the children of the Donbas’.

Another category that was actively attacked by Russian and pro-Russian users was Western journalists. Mostly it was about generalised ‘Western journalists’ rather than representatives of specific foreign media. For example, they wrote that ‘Western journalists are watching the murder of children in Donbas, the rise of neo-Nazism in Ukraine <...>’. They were accused of allegedly false coverage of the war and Russia’s role, which eventually boiled down to accusations of ‘Russophobia’ and working according to the methods of the ‘collective West’.

’The West contributes to the murder of Donbas children’

A separate group of messages concerned Western support for Ukraine. The vast majority of posts on this topic were dedicated to the supply of Western weapons to Ukraine. There was an entire campaign launched by Russian propaganda accusing Western countries of allegedly sponsoring the ‘murder of Donbas children’: allegedly, by providing weapons to Ukraine, they become accomplices in war crimes. For example, there were messages that ‘Donbas children are killed with weapons provided by the United States, France, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, the Netherlands and other countries’. The NATO alliance was also mentioned. However, naming specific states is rather an exception, mostly all accusations of Russian propaganda boil down to the notion that ‘the collective West continues to finance the deaths of Donbas children and provide Ukraine with new types of weapons’. Therefore, we can assume that the purpose of this campaign is not to persuade Ukraine’s partners to stop providing assistance. It is mainly intended for the ‘domestic audience’, which is offered yet another reason to hate the West.

At the same time, some Russian and pro-Russian users held the West ‘directly responsible’ for the killings. Most often it was the USA. For example, ‘the blood of Donbas children is on the hands of the American military’. As a general rule, Russia often uses references to the United States in disinformation campaigns about the war in Ukraine. Among the most popular narratives are ‘the US provoked the war in Ukraine’, ‘the US is leading the war in Ukraine’, ‘America is fighting with the hands of Ukrainians against Russia’, ‘the US is profiting from the war in Ukraine’, etc.

Despite the fact that the message ‘the West contributes to the murder of Donbas children’ was aimed at ‘domestic consumers’, they tried to give it ‘international appeal’. Specifically, a statement of alleged Western journalists working in occupied Donetsk was actively reposted for this purpose. It was presented as a ‘call of international journalists’, but no names or at least publications were indicated in such posts. Overall, all these arguments were intended to contribute to the demonisation of the image of the ‘collective West’ in the eyes of the audience of the Russian and occupation social media segments.

’Ukraine must answer for its crimes’

Another notion promoted by Russian propaganda to the domestic Russian audience and the occupied territories of Ukraine was the promise that ‘Ukraine will be put on trial for crimes against the children of the Donbas’. A noteworthy feature of such posts was the lack of reference to appeals to international courts or organisations. The majority of their arguments were generalised. They claimed that ‘Ukrainian war criminals are waiting for a tribunal’, that ‘crimes of Ukraine have no statute of limitations’, etc. In this context, Russian disinformation reverted to messages about the West, allegedly ‘Ukraine kills children with the tacit consent of the West’. For the most part, such messages were rather a preparation for the next stage of the disinformation campaign.

While Russian and pro-Russian users spread allegedly ‘legal ways’ to influence the situation, such as tribunals, courts, etc., in the posts centred on the messages that ‘Ukraine must answer for its crimes’, in the next stage of the disinformation campaign the central message was that ‘the war in Ukraine (which they call a special military operation. — DM) is revenge for the children of the Donbas’.

’The war in Ukraine is revenge for the children of the Donbas’

The assertion that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is a ‘revenge’ is nothing new. In this context, it is worth mentioning the myth about the alleged oppression of the eastern regions of Ukraine by the western regions of the country. Russia used all these ‘pretexts’ to justify its aggression and put the blame on the Ukrainian government. So the ‘revenge for the children of the Donbas’ is another variation on this concept. For example, if in the statement ‘by killing the children of the Donbas, the Ukrainian state has lost the right to exist’ you replace ‘the children of the Donbas’ with ‘oppression of Donbas’ or ‘Banderites/Nazis’ the message will remain the same. It thus appears that Russian propaganda chooses different ‘entry points’, but tries to lead its audience to a single (favourable to the Kremlin) conclusion. This is also true for the argument that ‘Ukraine deserves to suffer for the murder of Donbas children’ or ‘Ukraine will suffer for the suffering of Donbas children’.

Russian propaganda uses this message not only to ‘explain the reasons’ for the full-scale invasion, but also to ‘justify’ all related crimes. For example, ‘for the murdered children of Donetsk and Makiivka <...> Ukrainian positions were attacked’ or ‘shells with the inscription ‘For the children of the Donbas’ hit the fortified area of the Ukrainian army in Donbas’. Reports about shells were most often spread after the so-called Day of Remembrance of Children-Victims of War in the Donbas in the occupied part of Donetsk region, marked on July 27 by the occupation authorities. The notion that Ukraine deserves to suffer for the suffering of Donbas children is accompanied by massive missile attacks on Ukrainian cities and infrastructure. For example, on October 10, during the first massive shelling of the energy system, messages like these dominated the Russian segment of social media and on the occupation Telegram channels.

The Kremlin propagandists have been preparing the audience in Russia and the occupied Ukrainian territories for this idea for some time, gradually bringing them to it. That is, we can trace the path of development of this message: first, Russian and pro-Russian audiences are made to believe in Ukraine’s crimes against the children of the Donbas, then they accuse the West of complicity and financing of these alleged crimes, then they create the appearance of attempts to ‘legally influence’ the situation and allegedly try to bring Ukraine to justice; and the culmination is ‘the West turns a blind eye to Ukraine’s crimes against the Donbas’. After that, there is a transition to the message that ‘the war is revenge’, with Russia portrayed as an alleged ‘saviour’ of children and civilians in the Donbas. At the same time, Ukraine and the West are demonised, with more and more crimes being attributed to them.

Whom Russian propaganda mentions when it talks about ‘children of the Donbas’

In posts mentioning children from the occupied territories of Ukraine, the people quoted fall into two categories. The first are Russians who distribute aid, allegedly improving or making the living conditions of people from the occupied territories similar to Russian ones. The second are officials of the occupation authorities who meet with the Russians and approve of their actions.

Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian Children’s Ombudsman, is the most frequently cited Russian official. Similarly, Alexander Bastrykin, the head of the Investigative Committee of Russia, is often mentioned and quoted in the Russian social media segment and occupation Telegram channels talking about criminal cases opened on the facts of deaths of children in the occupied territories of Ukraine.

Russian governors, officials, and members of parliament have also repeatedly promoted messages advantageous to the Russian authorities about helping children from the occupied territories of Ukraine — if not with shelter or treatment, then with gifts. For example, the occupation segment of Telegram disseminated information about gifts to children from the occupied territories from governors: Vadim Shumkov from the Kurgan region, Vasily Golubev from the Rostov region and Alexander Moor from the Tyumen region. Deputy Chairwoman of the State Duma of Russia Anna Kuznetsova, Deputy Chairman Boris Chernyshov, and State Duma member Viktor Vodolatsky also distributed gifts and promised to improve the lives of ‘evacuated’ Ukrainians. Representatives of the Russian ruling party ‘United Russia’ also cursed Ukraine while giving gifts to children. Among them, in particular was Secretary of the General Council of United Russia Andrey Turchak and his deputy Daria Lantratova, as well as their colleagues from other central bodies of the party Alexander Kalinin and Alexander Sidakin.

There were also many other officials. In particular, Russia’s Commissioner for Human Rights Tatyana Moskalkova and the Commissioner for Children’s Rights of Moscow Olga Yaroslavskaya were involved in justifying the deportation of Ukrainian children. Additionally, officials who were relevant to the topic were given the opportunity to speak. Russian Minister of Education Sergey Kravtsov spoke about Russia’s assistance in preparing for the school year and transition of the occupied territories to Russian educational standards. Similar statements were made by the ministers of the Russian federation subjects, for example, the Minister of Education of Bashkortostan, Aibulat Khazhin.

The statements of the occupation authorities largely mirrored those of Russian authorities. Most of the occupiers’ speeches were about the fact that ‘Ukraine is killing Donbas children’ and that ‘it is a good idea to evacuate to Russia’. There were more of these messages from employees of Donetsk’s occupation authorities than from collaborationists elsewhere. Denis Pushilin, leader of ‘DNR’ militants, ranks first in terms of the number statements, followed by his adviser and ‘children’s ombudsman of the ‘DNR’ Eleonora Fedorenko, as well as ‘Minister of Foreign Affairs of the ‘DNR’’ Natalia Nikonorova. They are the main speakers on the topic of Ukrainian children being sent to Russia. The quotes of Pushilin, Fedorenko, and Nikonorova are widely shared in the Russian segment of social media to reinforce the picture painted by Russian propagandists. They can later serve as evidence in criminal cases on the deportation of Ukrainian children.

Which countries Russian propaganda mentions when it comes to ‘children of the Donbas’

The context of mentions of countries in posts about ‘children of the Donbas’ that spread the ideas of Russian propaganda can be divided into two categories: aimed at demonisation and intended to convince of ‘support for Russia’.

The United States, Lithuania, and Poland are often mentioned in the first category. In particular, the US was mentioned in messages about ‘facilitating murders by providing weapons to Ukraine’. Russian propaganda mentions France, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and the Netherlands in the same context. There were mentions of the USA, Moldova, Hungary, and Lithuania in conjunction with the claim about ‘the West’s indifference to the fate of Donbas children’. As for Poland and the United Kingdom, which are labelled by Russian propaganda as ‘Anglo-Saxons’, the accusations are more aggressive: the Polish authorities are accused of kidnapping children, allegedly ‘taking children away from Donbas refugees’; and the British get accused of ‘paedophilia’. Some of these messages have been circulating even in the Ukrainian media for several months. Notably, the list of states mentioned in the narrow topic of ‘children of the Donbas’ is quite similar to the general list of states that Russia has often mentioned in its disinformation campaigns since the beginning of the full-scale invasion in Ukraine. Read more about the countries and leaders that ‘hinder’ Russia in the war with Ukraine here.

Almost all of these accusations were spread as rumours, only a few were based on stories that are difficult to verify. As with most of its falsifications, Russian propaganda does not attempt to convince the audience that the facts are true; it works to undermine the credibility of specific countries.

At the same time, Russian propaganda promotes the message that Russia ‘does not need the approval of the West’. However, in order to instil certain ideas and create a ‘halo of legitimacy’ of its actions, it resorts to spreading allegations of support from foreigners. For this purpose, the Russian propaganda machine mentioned Cyprus, Germany, Italy, and even Venezuela. Mostly, it was reported that these countries are concerned about the fate of the ‘children of the Donbas’, protest ‘against the crimes of Ukraine’, hold exhibitions or rallies with portraits of ‘children of the Donbas’. This information was often presented without context. Instead, a more detailed check showed that almost all these rallies and exhibitions were held by Russian diasporas and centres in these countries.

As part of its information operations, Russia also attempts to legitimise its so-called partners, consisting primarily of Belarus and quasi-entities, such as Russia-occupied Abkhazia. There were many promotional materials disseminated about meetings between the occupation administrations and Russian officials to resolve ‘the problem of the Donbas children’, transfers of ‘humanitarian aid’ and the deportation of Ukrainian children to camps, for example, in Belarus.

Although this list of countries is not exhaustive, the total number is not large. Russian propagandists are more prone to generalisations such as ‘the West’, ‘EU countries’, ‘Europe’, ‘Anglo-Saxons’, etc. This gives the Russian propaganda machine more flexibility in creating and disseminating messages, because the use of broader concepts allows them to avoid taking responsibility and mentioning specific examples in a particular country. Instead, they can inflate one fictional or real story to the scale of the entire ‘West’, thereby demonising all states that in the imagination of pro-Russian users may belong to the ‘collective West’. Read more about Russia’s anti-Western rhetoric during the full-scale invasion in the Detector Media study here.

Conclusion.

By spreading disinformation that focuses on the life of children during the war, in particular the so-called ‘children of the Donbas’, Russian propaganda seeks to discredit Ukraine and the Ukrainian authorities in the eyes of both its own and Western society. In the Russian propaganda stories about the life of children in the occupied territories and the war zone, the Ukrainian authorities and military appear as ruthless ‘punishers’ whose goal is to exterminate the so-called ‘people of the Donbas’, who ‘voluntarily chose to be with Russia’. By fabricating stories such as these, Russian propaganda seeks to create a false reality demonstrating that nothing will stop the Ukrainian authorities and army on the way to achieving their goal — the destruction of the so-called ‘people of the Donbas’, because they are going to do whatever it takes, even killing children. The very separation of ‘children of the Donbas’ into a separate category from other residents of the occupied territories is already a manipulation. That is, the propaganda machine deliberately exploits the sensitive topic of children’s life and safety in order to sway people’s emotions. They claim that poor children have no future without Russia, because they live under war conditions, constant shelling, do not remember peaceful life, and only Russia can save them from this harsh reality.

The Russian propaganda machine uses such disinformation as a kind of incentive to raise the morale of Russians. In particular, by calling the same ‘children of the Donbas’ Russian children (although some of them, as the propagandists themselves note, do not even speak Russian) and claiming that it is necessary to fight Ukraine to avenge them. Alternatively, it encourages Russians to adopt Donbas children, thus ‘saving’ them from the terrible Ukrainian ‘punishers’. Disinformation of this kind attempts to discredit not only Ukraine, but also Western countries, which, according to Russian propagandists, allegedly aid in the killing of Donbas children by providing Ukraine with weapons. Russia thus demonises other countries in the eyes of its society. Most notably, the United States and EU countries. By doing so, propaganda creates an alleged value gap, asserting the idea that people in these countries do not care about the lives of children; they do not care that children are dying in the Donbas, etc.

In addition, Russian propaganda portrays the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia as a rescue. It claims that Donbas children are being saved from Ukrainian ‘punishers’. However, according to the Ukrainian authorities, children are taken not only from the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, but also from other occupied territories of Ukraine. For instance, children were deported from the Kherson region. As of December 29, it is known about 13,876 Ukrainian children kidnapped by Russia. The Ukrainian government considers such actions to be an abduction of its citizens. However, Russian propaganda once again uses euphemisms, referring to its crimes as rescue operations.

The claims about protecting the ‘children of the Donbas’, which are circulated by Russian propaganda, become another justification for Russia’s invasion. These messages stem from a large propaganda narrative about the ‘8 years’ during which Ukraine allegedly destroyed the Donbas and massacred its citizens. However, while spreading all these messages, Russian propaganda ignores the fact that the affected ‘children of the Donbas’ and destroyed towns and villages appeared in Ukraine because of Russia, which began its invasion of Ukraine in 2014 with the occupation of Crimea and the attack on parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion, which began on 24 February 2022, Ukrainian children are suffering not only in Luhansk and Donetsk, but throughout the country. In particular, according to the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, as of 29 December, 450 children were killed and more than 800 injured as a result of Russia’s armed aggression. However, these figures, as explained by the government authority, are not final, because it is impossible to obtain data from the temporarily occupied and recently liberated territories. For example, on December 28, two children were wounded due to enemy attacks in the Kherson region. In addition, according to UNICEF, as of June 2022, more than two million Ukrainian children became refugees and left the country, and about three million more children, fleeing their homes from the war, became internally displaced. Speculating on the topic of ‘children of the Donbas’ and their suffering, Russia does not mention millions of Ukrainian children who suffered from its actions. Thus, Russia creates a distorted reality in which it appears as a saviour, not an aggressor.

This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Detector Media and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Visualisations prepared by Natalia Lobach and Oleksiy Pivtorak

Illustration: Natalia Lobach